17

Brad D. Olson; Jack F. O'Brien; and Ericka D. Mingo

Chapter Seventeen Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand characteristics of dehumanizing and harmful societal structures

- Understand which means are most effective to reduce harm when engaged in social and political change processes

- Understand how to engage in sustainable forms of activism

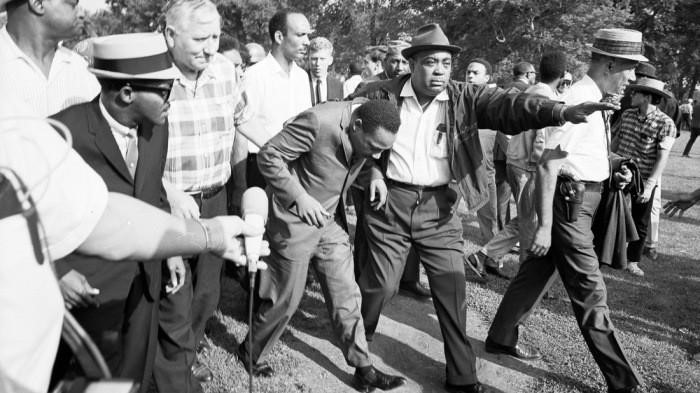

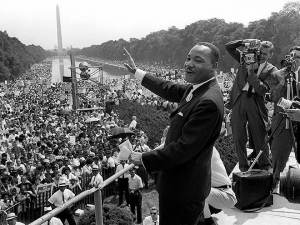

In the photo above, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is pictured leading 600 demonstrators on a civil-rights march through angry white crowds in the Gage Park section of Chicago’s southwest side. After King was struck by a rock, he was escorted by his bodyguard Frank Mingo. Frank later said: “No need to tell you anything different, I was sure scared. I got hit five or six times that day. But I didn’t mind. That was what I was there for, to protect Dr. King. My wife and I have three boys growing up. I felt that anything I could do to improve society would help them too.”

Part of the community organizing aspect of Community Psychology is understanding the long game, as the quote above nicely demonstrates. Many community psychologists work to reduce the symptoms of oppression through programming and community-based participatory research. Critical and liberation community psychologists, particularly ones engaged in activism, work to use psychology to confront oppressive actors and organizations. Frank Mingo worked diligently for the Poor Peoples Movement and the Back Home Movement, which was a part of a repatriation of the south by African Americans, laying claim to land that was legally theirs. Both Mingo and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. set examples of ways community psychologists can learn about courage and persistent involvement toward social change. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s writings and speeches, in particular, demonstrate ways in which community psychologists can use their skills to be effective and, at the same time, remain ethical and positive in their activism.

Community Psychology programs often focus on changing inequalities for people who are suffering, but the means have to be considered with extreme care. The message of this chapter is that rather than community psychologists being thought as the sole agents to “empower” others, we need to work together with community groups in collaborative efforts to foster their own empowerment. In other words, we can bring people together and work as allies with those who experience injustice (Olson et al., 2011).

Part of being an effective ally is turning our attention toward those responsible for structural violence. Structural violence is a way to understand that violence and harm are caused not only by individual actors but by unjust laws, dehumanizing structures, and other features of the environment—all of which, of course, were created by human beings. To summarize, we feel that attention should be placed on the actors, policies, rules, and structures that harm community members. As the well-known psychologist Amos Wilson said, “If you want to understand any problem in America, you need to focus on who profits from that problem, not who suffers from the problem” (1998). Wilson is referring to those who have power to engage in any form of injustice whether it is due to greed, indifference, or racism.

The key question is: how do community psychologists attempt to tip the scale and change oppressive organizational, corporate, or governmental policies? It is often difficult to fight a powerful opposition, and the obstacles can seem insurmountable, as they were during the civil rights movement of the 1960s. When the goals seem impossible, and a sense of hopelessness and helplessness has set in, values and passion can provide the drive to continue working for social justice. We will show in this chapter examples of how this might be accomplished, as well as how you can remain inspired and motivated through it all.

COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY AND OPPRESSION

Amos Wilson (1998) felt that the elite effectively secure and enhance their power, hiding their real actions and motivations, all the while appearing not to do so. This can often leave those who have been oppressed to believe that they themselves were responsible for their struggles. Part of the work of community psychologists is to pay attention to those who have experienced oppression as a result of this structural violence. This work within communities is to help its members unravel these kinds of manipulations. To understand oppression and those who are oppressed, Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed offers important insights. For Freire (2007), the oppressors’ psychology is one of hierarchy, suppression, and dehumanization, and those oppressors will never liberate the oppressed. Freire felt that our ordinary way of thinking, “an eye for an eye,” would just lead to the oppressed replacing the oppressor, only to keep dehumanizing structures the same. Community psychologists work with community members to help them identify aspects of structural violence in order to change those structures. Follow this link for some helpful definitions related to oppression and power.

Examples of oppressive systems are the Guantánamo Bay detention camp, located in the Guantánamo Bay US Naval Base in Cuba, and secret Central Intelligence Agency black sites throughout the world. At Guantánamo, prisoners’ conditions of detention fell under human rights definitions of torture (find more about the abuses at Guantánamo from the perspective of a detainee). The torture program at the Central Intelligence Agency black sites designed by psychologists led to permanent psychological harm of the Muslim detainees. There were some psychologists who sought to expose these human rights violations. This is how it came about: due to media reports of extreme interrogations by the US government, the American Psychological Association (APA) convened a task force in 2005 to examine psychological ethics in national security, and this task force endorsed the continued presence of psychologists to use their psychological tools against detainees.

Following the task force report, members of the Coalition for an Ethical Psychology mobilized to hold APA accountable to its own ethical standards. The hallmark of the Coalition was the unmasking of policies regarding unethical psychologist involvement in torture. The following case study describes this coalition and some of its work.

Case Study 17.1

Coalition for an Ethical Psychology and the Hoffman Report

A community psychologist, a psychoanalyst, a historian of psychology and other clinical psychologists are leaders of the Coalition for an Ethical Psychology. The members of this coalition created a collaborative, non-hierarchical place for their activist work. They shared information and developed key allies with other organizations who could aid them in their efforts to expose the collusion, pertaining to the torture program, between the APA and the national security sector. By working with these allies, stakeholders in and outside of the field of psychology, their efforts eventually led to James Risen’s New York Times articles that detailed this collusion. The articles revealed APA’s collusion in allowing psychologists to be engaged in interrogation procedures that involved torture, and this led to the APA commissioning an independent review by David Hoffman, eventually culminating in what has been called the Hoffman Report. The Hoffman Report presented communications and actions taken by APA officials and members of the Department of Defense, Central Intelligence Agency, and Department of Justice that pointed to coordinated efforts and knowledge of APA Ethics Code subversions. The Hoffman Report and the aftermath led to increased accountability within the organization. Video discussions by Coalition members and their allies can be found below.

The creation of the Coalition for an Ethical Psychology is an illustration of what psychologists can do to combat oppressive forms of injustice, and in this case, the violation of human rights.

USE OF PARTICIPATORY MEANS

One job of community psychologists is to engage in dialogue with the oppressed and find what Freire called their generative themes, the core issues that face a group (Freire, 2007). Freire believed that community members are the best ones to identify the nature of the problems they face and participate in the solutions. When they align themselves with those facing oppressive conditions, they can, together, start directing their attention to unjust actors who control structures. For example, when the UN created the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, 2006), those in the disability community objected because they had been left out of this process. People with disabilities were successful in demanding that they were the best ones to shape the foundational principles of the Convention, and they indeed became instrumental members. The famous phrase that came out of the disability community was “nothing about us without us.” Follow this link to hear young participants’ perspectives within the process.

Within Community Psychology, Julian Rappaport (1981) coined the term empowerment, which is very compatible with the value of helping the oppressed gain access to resources and increase self-determination. Rappaport often cautioned community psychologists against suggesting they were in charge of “empowering” community members. Rather, the empowering process is one in which all parties work together to bring about a greater sense of collective efficacy and work to equalize power throughout society.

Rappaport made an important distinction between empowerment and other approaches called needs-based and rights-based strategies. Needs-based strategies put those with the lived experiences on the dependent side of the hierarchy. Trying to deal with their needs, and focusing on pathologies or limitations becomes the focus. When focusing on the rights-based strategies, it is too easy to adopt a position of fighting “for” but not “with” community members. The Third Way of Empowerment (Rappaport, 1987), as described in this chapter, is very much aligned with working with community members. However, sometimes it is difficult to work directly with the community that is oppressed. As in the example of the Coalition in Case Study 17.1, it was impossible to work with the detainees because they were in secluded and restricted detention settings. Nevertheless, the Coalition communicates with multiple groups in an effort to help “educate” rather than “train” others. “Training is defined as teaching a group what to think rather than how to think. This makes the people dependent rather than assisting in developing skills which could be used for independent activity. It rewards behavior that operates against their group’s interest, promoting individual rather than group achievement, and instilling negative self-concepts and low self-esteem”

– Bobby E. Wright (Anonymous, 1982)Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed was similarly all about a new form of non-hierarchical education. Like the “empowerment process”, it was about collaboration and dialogue––where the teacher is also the student, and the student also the teacher. When working with communities, empowerment involves everyone working toward common, mutually-decided upon goals.

Community psychologists who engage in activism can also learn much from Rappaport’s notion of paradox, which is something that combines what seem to be contradictory qualities (Rappaport, 1981). In doing community work, we often encounter paradoxes, where two apparently contradictory truths do not necessarily contradict each other. For example, one paradox is that the Coalition for an Ethical Psychology was engaged in an empowerment process, but there was no direct contact with the prisoners, the people they were attempting to empower. Although this might seem to be a paradox, it is possible to do empowerment work and not be in direct contact with those who are oppressed. In engaging, investigating, and highlighting the side not receiving enough attention, empowerment can occur.

MEANS MATTER

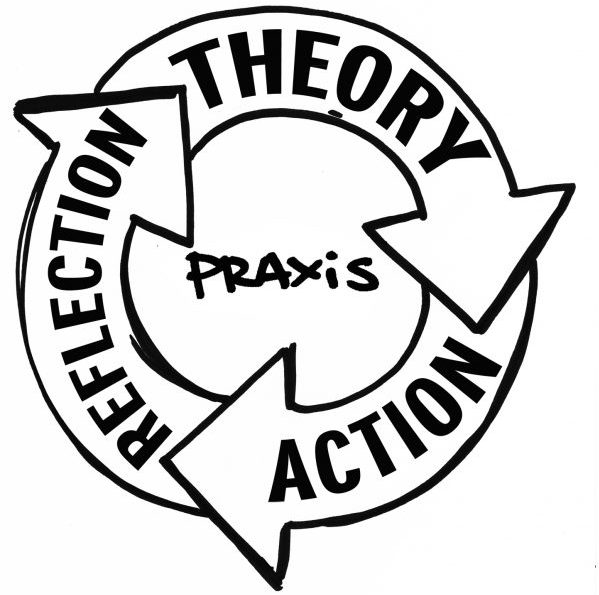

Praxis means putting an idea or theory into practice. This is often a repetitive process whereby a theory, lesson, or skill is turned into an actualized action. Community psychologists learn from community members, co-design research projects, and try to put that learning into real action and activism. They then see how things work, and then return to the drawing board. Ethics, morals, and values are all essential parts of the praxis process. But here there is sometimes a division between those who use any means to get to their goals met and others who feel the means have to be ethical. Several community activists, such as Saul Alinsky and Malcolm X (particularly in his early life) felt that any means could be used as long as the ultimate goal is just. Sometimes using any means results in cutting corners or even harming others.

To use an analogy, the ring of power in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings is often attempted to be used for good, but it can only be used for evil. The characters with the best of ends in mind can become corrupted, due to the influence of the ring. So, what we are suggesting is that the means of reaching one’s goals in social justice is of importance. Poet and activist Audre Lorde famously declared, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (2007). If the problem is oppression and violence, using oppression and violence to achieve one’s goals might not be effective or just. Malcolm X realized this toward the end of his life when he sojourned to Mecca and saw people of all races, nationalities, and backgrounds praying together in unity. This radically altered his views on working to dismantle the oppressive power structures in this country, and he began preaching more about love and collaboration. To demonstrate the difference in approach to the means of activism, Case Study 17.2 compares different means of two influential social activists.

Case Study 17.2

Alinsky and Gandhi

Alinsky and Gandhi were both tricksters in defying powerful individuals, but they were also different in the means with which they carried out their work. Alinsky in Chicago believed in confidently insulting those in power and even using tactics of deception. In other words, all means could be used to get to the objective. As an example, in Alinsky’s book Rules for Radicals, he recommended: “find their [the opposition’s] rules and use those rules against them–because they find these rules precious and they cannot live up to them.”

A different approach was used by Gandhi in British Colonial India, where he engaged in nonviolence and humility, attempting to make the means ethical, and always striving to work with love for all human beings. In India in the 1930s, a British “rule” or “law” was a salt tax, making it illegal for the people of India to make or sell salt or even to collect it from the sea. Gandhi engaged in civil disobedience by initiating a march to the sea to collect the salt. This act inspired all of India and made the British look foolish, as they were unable to stop the march. In this way, Gandhi successfully took on the British without using their oppressive and violent tactics. His means were just and not corrupted in radical opposition to British rule. But, as is often the case when engaging in defiance of oppressive systems, Gandhi was punished by incarceration for his salt march.

It is in choosing the means of activism that a tempting crossroads presents itself to community psychologists, and we would argue for the adoption and use of ethical means to reach the goals.

The Means of Working in Partnership With

The means by which we partner with community members also matters. Community members are sometimes labeled with oppressive terms: the disenfranchised, vulnerable, the marginalized, the poor, those of “high risk”. The words we use do matter, and even the term “community organizer” suggests a person who is in charge of the collaborative spirit. Therefore words that suggest hierarchy, where one might have more power than others in the change process, are outside the spirit of Community Psychology.

In any praxis-based campaign, there is also a need to address the oppressor’s dehumanizing and colonizing nature. But, as we saw with Gandhi and with Martin Luther King’s work, this can be done in an ethical way that does not replicate the oppressors’ way of being. For an example of how to practically consider and address colonization using Community Psychology tools, learn more from Demystifying Decolonization: A Practical Example from the Classroom.

Ultimately, an important task of the community psychologist engaged in activism is to try to ethically persuade others using the tools of research and community-based action. Some individuals will never change and with others, it will take considerable time. Sometimes in a democracy, what is needed is to convince a majority of people, and encourage them to continue to engage in voting and social action. Community psychologists can also help keep groups of people cohesive, effective, and willing to engage in a long-term struggle despite criticism, insults, threats, and even risks to one’s career.

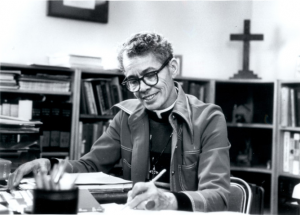

The Means of Assessing and Working on Oneself through Self-Purification

The activist’s journey is not only outwards toward bringing about change, but is also inward. It involves a thorough examination of one’s own imbalances, flaws, virtues, and motivations. This is often referred to as part of the “self-purification” process. When considering one’s motivations, one might ask if they are for accomplishing one’s own goals and priorities or if they are for the advocacy of others. An important civil rights activist who became the first female African American Episcopal priest was Pauli Murray who expressed a modest realism that comes from a life of self-purification. She stated, referring to the many activist campaigns she engaged in:

“In not a single one of these little campaigns was I victorious. In other words, in each case, I personally failed, but I have lived to see the thesis upon which I was operating vindicated. And what I very often say is that I’ve lived to see my lost causes found.”

This self-purification process is often a necessary element in social and political change, which as described earlier, is by doing it “with” not just “for” others. Gandhi, for example, believed purification processes were the most powerful antidote to external violence in the world, and helped a person sacrifice one’s well-being for the larger cause. Gandhi’s purification was a daily process which was clear to anyone who looked at how he both dressed and ate. The purification process could even be seen in how he responded to being attacked. Gandhi was incarcerated by the British after the salt march, and many other times was abused by powerful officials. But due to these abuses, social change occurred when the public was shocked and angered by the way he was treated by government officials. The act of sacrifice shifts public perceptions of the horrendous situations facing those being oppressed. The sacrifice and pain endured by such individuals as Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela of South Africa existed in a broad, public view, which can galvanize public support for social change.

The Means of Exposing and Changing the Oppressive Power Structures

It might appear that activism has only a loosely structured set of rules. In fact, there are no definitive rules to the liberation process, as much depends on context and on the many paradoxes one encounters when trying to change societal systems. Many community activists, such as Alinsky, focused on finding the immoral weaknesses or vulnerabilities of those in power, and inciting the police or public officials to over-react. The activist takes action, like in Gandhi’s salt march, in order to get the powerful system of oppression to react to the defiance.

Therefore there are patterns that help us, but activism is less a set of procedures that can be learned and memorized and more a process of experimentation. This perspective frees one to take risks, but our goal is to use ethical means so that when we are wrong, we will not bring about harm to others. It also gives us additional motivation, and that is of learning, invention, and searching for truth. Altering the path of an abusive power structure is intimidating, and Gandhi saw this as experimentation toward truth. Gandhi and King’s commitment to nonviolence showed the real possibilities, even death, to those that challenge the status quo. These activists embraced a self-purification process, but as Gandhi said, “non-violence laughs at the might of the tyrant” (Gandhi, 2001, p. 57). Nevertheless, both Gandhi and King used self-purification to avoid hating the enemy. Gandhi described this through a story about a burglar breaking into one’s house and the need to treat the thief as family, a concept referred to as critical kinship (Olson et al., 2011). We need to be critical, but at the same time see the opposition as kin.

One might ask whether students can participate in this process of taking on the power structure. The next case study shows it is possible, and it began with student reactions to the lynching of 128 African Americans living in the south. These killings had been unsolved for decades, and when the Justice Department withheld information about these civil rights injustices, it operated as an oppressive power structure. The hiding of this information can lead to cross-generational trauma, as the victims’ immediate loved ones and descendants have to live with the agony of unanswered questions, such as “What happened? Who did it? And why?” The students in Case Study 17.3 sought to answer these questions by confronting the source of the structural violence.

Case Study 17.3

Students Taking Action For Justice

A teacher of Government and Politics at Highstown High School in New Jersey told the students about this historical civil rights injustice, the unsolved lynching of 128 African Americans. They merely asked, “Should we try to do something?” (Jackman, 2019). In a true community organizing fashion, the class made it their mission to bring some semblance of peace of mind to the loved ones of the victims. The class drafted a bill that would force the compilation and immediate release of all the withheld case files to the public. The students understood the importance of focusing on the historical injustices and rectifying them. With the implementation of their activism, the students demonstrated a successful model of praxis. The students conducted research in order to fully understand the issue, took the time to meet with the families of the victims, and made sure to set the agenda through a strategic media campaign. Their efforts were noticed by two US lawmakers, who advocated for the bill and encouraged citizens to pressure the President to sign the proposed bill into law. The students also engaged the President through social media, and the high school allowed the cancellation of classes to undertake the social media effort. The President did sign the bill to release the withheld cases.

The students demonstrated the power of effective community organizing, community engagement, and speaking truth to power in order to take on an oppressive power structure.

PRAXIS AS AN ALTERNATIVE PROCESS

A social justice campaign is rarely a single event or a single march. Organizations begin and fizzle but activists continue to fight for justice. Having a framework for the intricacies of social change is needed for the long-term process to be successful. As discussed earlier, this process is referred to as praxis, which is the cycles of participatory action and research: community input, research, action, and reflection (Olson et al., 2011). Part of praxis is seeing what works and what does not work. When barriers and obstacles are insurmountable, certain tactics need to be let go of in order to search for new creative ways. Community psychologists plan for readjustments, adaptations, setbacks, small wins, and unexpected barriers. They also need to remind themselves of the higher goals they are trying to achieve. A long-term commitment is often the best ally a change agent has, along with allies from the community, in bringing about real change against those who control the status quo (Jason, 2013).

The analysis moves in spirals toward the best possible fit: the combination, the generation, the cyclical action—this is what a temporal campaign involves, until there is progress—a small win, and then another, and another, until transformational change gets going. To implement these processes, finding or creating alternative social settings helps protect individuals and the community from daunting oppression and barriers to change.

We are all part of many settings, some of which are more or less consistent with our social justice identities. To the extent one finds oneself in settings that support oppressor norms, it is possible to work from the inside to change them. When impossible to change, it is often possible to leave a setting, and seek or create new settings that better support one’s values. The creation of alternative settings has been described by Seymour Sarason, whose book The Creation of Settings and The Future Societies has much information on these alternative settings (Sarason, 2000). The creation of such settings is exactly what is needed for the sustainability of campaigns for social justice. The creation of alternative settings takes time and commitment, but they can provide an essential home base for sustainable activist work.

Sustainability of the Campaign Process

In a praxis-based campaign, it is important to consider what needs to be done first. One of the earliest stages involves generating, with others, hypotheses or ideas for change. A logic model can be developed that provides an outline, and a theoretical structure of how assets and activities are likely to help obtain short, intermediate, and long-term goals. The plan can be simple sketches that represent how one is going to break through the barriers ahead to meet the eventual long-term objectives. This is like a planning notebook and one can connect it with experiences, arguments, and evidence. If the logic model is created as a visual with concepts and arrows, it is possible to see the whole plan in a single glance. The whole group can then discuss and revise, using it as a conversation piece to connect it with all of the group’s experiences and where the group is trying to go together.

Ultimately, community psychologists measure whether or not their actions and efforts were successful in the short and long term. But what should the outcomes be? Certainly, it is useful to know if the program was successful. What actions helped? When it worked, what was the active combination of ingredients that had the effect? How do we study and help amplify where good grassroots connections are happening? Another goal is to understand how we can make a campaign more sustainable. How can capacity be built when campaigns fizzle out? Can we hold onto the small wins and keep going? To answers these questions, and to avoid burnout and keep the campaign sustainable, it is important to pace oneself, and ensure that self-care and mutual education are present at every part of the process (Olson et al., 2011).

Let’s provide another example of a problem that was encountered at a university. One of the highest members of the university’s administration had been actively involved in the APA’s collusion that made it permissible for psychologists to be involved in interrogation settings that included torture. As described earlier in the example with the coalition, this collusion came to the public light following the July 2015 publication of the Hoffman Report (see also the material cited in Case Study 17.1). The administrative official was mentioned dozens of times in this Report, and when the school student newspaper emailed a psychology undergraduate student named Jack O’Brien, asking for his reaction, the following case study shows what next occurred.

Case Study 17.4

The Vincentians Against Torture Coalition

Jack O’Brien was interviewed with the reporter for the school newspaper, and he gave his thoughts regarding the university official who was alleged to have been instrumental in the facilitation of changing APA policy and procedures that allowed for human rights violations perpetrated by psychologists in interrogation settings. After being quoted in the school paper, O’Brien started a petition to remove the official from the university and organized the Vincentians Against Torture Coalition. He collaborated with several local human rights organizations such as the World Can’t Wait and Voices for Creative Non-Violence. He also networked with student groups, such as Students for Justice in Palestine and Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan, that were invested in the issue. His petition amassed over 700 signatures, and this ongoing struggle was prominently featured in many articles in the student newspaper. O’Brien next organized a press conference on campus, which was featured on local television news channels and written about in newspaper articles in the Chicago metropolitan area.

However, even though there was a high level of media visibility and protests involving faculty, staff and students, ultimately, the President of the university announced that the school would not be taking any actions against the university official. In the short run, the campaign had not dislodged this official, but a few years later, both the university President and the official that had been the focus of these protests left the university. Although the protests and the media attention might not have been a direct cause of both officials departing, they contributed to concerns that many university employees had regarding their performance.

Following graduating from college, O’Brien continued to invest himself in the torture/human rights issue affecting psychology, such as organizing a symposium addressing the issue at a national psychology convention. As in Case Study 17.1, both activists had to stick with the torture issue for a long time in order to see meaningful change occur in the profession of psychology.

SUMMING UP

The work of Community Psychology does not support hierarchical social and political change. Rather it is non-hierarchical, working from the bottom up with grassroots sources in the community. The voices of the people are the main data that are used. Praxis possesses an improvisational quality, and it is experimentation at its best—as there are many advantages to this approach when working with the community to advocate and engage in social change.

Community psychologists work with community members to mutually educate each other in order to reach more complete understandings of the issues they are facing, and the nuanced impact of these issues. As activists, community psychologists are facilitators, a part of the process, and are intentional and respectful. When community psychologists analyze systems, they use skill and an ecological lens (as pointed out in the first chapter, Jason et al., 2019), combined with respect for the people they work with. As Coalition for an Ethical Psychology member Roy Eidelson advises, aim to call “…attention to daily injustices, whether that’s working hard for less than a living wage or facing discrimination in housing, education, or law enforcement,” as a first step in challenging and changing dehumanizing structures (2018, p. 203).

Community psychologists, whether they are practitioners or scholarly activists, try to untangle the blocking points and hurdles to social change. Often, the job is to find the paradoxes and tension points, and to help show the world the abuses, just as was done by the leading activists of the past. By using honesty, truth, and the strategies outlined in this chapter, you and your community partners can begin to advocate for long-term change, and bring about a more equitable distribution of resources for a better world.

Critical Thought Questions

- What social or political changes do you want to be achieved in the world? Can you think of a praxis, a process, and put it in a logic model, that could best help you as you engage in activism?

- Can you think of an “alternative setting,” in your own life? A group of people, your tribe, who share a set of values with you, or want to see the same injustice righted? Can you think of ways that you could collaboratively work with them to bring about change?

- Think about some of the tools and skills that were mentioned as necessary to successfully bring about social and political change, or second-order change, through activism. Did you identify with any of these tools, have you used any of them in your own life, and how could you use them as an agent of social change?

- The authors argued that the ends never justify the means. Do you agree with this statement? Reflect on why or why not.

- Do you see yourself, your identity and reality, as being more or less in the oppressed or the oppressor group? Or some combination of both? How can we think about Freire’s categories as less about the oppressor and oppressed, and more about intersecting identities that still recognize asymmetries of power?

Take the Chapter 17 Quiz

View the Chapter 17 Lectures Slides

____________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Anonymous. (1982). Bobby E. Wright. Journal of Black Psychology, 9(1), iii-vi.

Eidelson, R. (2018). Political mind games: How the 1% manipulate our understanding of what’s happening, what’s right, and what’s possible (1st ed.). Green Hall Books.

Freire, P. (2007). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Gandhi, M. K. (2001). Non-violent resistance (satyagraha). Dover.

Jackman, T. (2019, February 23). ‘From students in high school all the way to the president’s desk.’ How a government class fought for the release of unsolved FBI civil rights case files. https://www.washingtonpost.com/crime-law/2019/02/23/students-high-school-all-way-presidents-desk-how-government-class-fought-release-unsolved-fbi-civil-rights-case-files/?utm_term=.f7d295ead2dc

Jason, L. A. (2013). Principles of social change. Oxford University Press.

Jason, L. A., Glantsman, O., O’Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. (2019). Introduction to the field of Community Psychology. In Jason, L. A., Glantsman, O., O’Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/intro-to-community-psychology/

Lorde, A. (2007). The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. In A. Lorde (Ed.), Sister outsider: Essays and speeches (pp. 110- 114). Crossing Press.

Olson, B. D., Viola, J., & Fromm-Reed, S. (2011). A temporal model of community organizing and direct action. Peace Review, 23, 52-60. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402659.2011.548253

Rappaport, J. (1987). Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology. Journal of Community Psychology, 15(2), 121-48.

Rappaport, J. (1981). In praise of paradox: A social policy of empowerment over prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00896357

Sarason, S. B. (2000). Barometers of community change: Personal reflections. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology (pp. 919-929). Kluwer/Plenum.

United Nations. (2006, December 13). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://www.ohchr.org/en/hrbodies/crpd/pages/conventionrightspersonswithdisabilities.aspx

Wilson, A. (1998). Blueprint for black power: A moral, political, and economic imperative for the twenty-first century (1st ed.). Afrikan World InfoSystems.

A focus on the individual where the influence of larger environmental or societal factors is ignored.