10

Fabricio E. Balcazar; Christopher B. Keys; and Julie A. Vryhof

Chapter Ten Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Specify different levels of empowerment

- Understand how we can contribute to power redistribution

- Learn ways to take action to make changes in communities

The cries of “Black Power!”, “Student Power!”, and “Power to the People!” rang out in the 1960s and beyond. The idea of power was central to those social movements. The work of those groups led to changes in civil rights, gay rights, and women’s rights. For example, the Women’s Movement raised important issues regarding women’s relative lack of power in personal relationships and their lack of opportunities in the workplace and larger society. Oppressive conditions supported by men-driven laws and policies in the larger society affected women on the individual, organizational, community, and societal levels.

Many participating within these social change movements experienced greater empowerment, which means gaining greater influence and control over important matters in one’s life and environment. Coupled with visions of hope and possibility, empowerment helped spur movements for positive social change for African Americans, students, women, Latinx, LGBT individuals, people with disabilities, Asian-Americans, prisoners, and people with mental illness, among many other groups.

Rappaport (1981) proposed that empowerment should be a primary focus of Community Psychology. He believed that empowerment is about helping those with less than their fair share of power to understand their own situation and gain more power. For Rappaport, empowerment includes considering people’s needs, their rights and their choices, and it captures the breadth of concern with the powerlessness that many groups experience.

To fully address the powerlessness of individuals and groups, efforts toward empowerment must be made on multiple levels. At the individual level, awareness of one’s lack of power can make one more likely to work towards increasing personal power. At a higher level, legal and societal sides of oppression may give rise to societal and political change. Thus, empowerment is a multilevel concept that impacts individuals, organizations, communities, and societies. From these beginnings, empowerment has come to be a key idea in Community Psychology and has also been important to fields such as Social Work, Public Health, Education, Political Science, Anthropology, and Community Development (Keys, McConnell, Motley, Liao, & McAuliff, 2017). Now, let’s consider how empowerment is thought of at different levels of analysis.

Individual Empowerment

Individual empowerment allows people to exercise control and increase self-efficacy. Self-efficacy can be described as developing a sense of personal power, strength, or mastery that aids in increasing one’s capacity to act in situations where one feels a lack of power. Individual self-efficacy is sometimes considered a “westernized” or “individualistic” construct built on the idea that simply having a belief in one’s ability to achieve a certain outcome is all a person needs for self-empowerment. This would imply that an internal belief in oneself is both sufficient and desirable for changing a one’s life. But change in self-efficacy without real change in one’s life cannot truly be called empowerment (Cattaneo & Chapman, 2010).

Psychological Empowerment

In contrast, psychological empowerment at the individual and group levels requires increased awareness and understanding of the factors that influence our lives. It is a process by which we become aware of the power dynamics that occur at multiple levels in our lives. This could be something like becoming aware of being treated differently due to the color of one’s skin, or how the lack of resources in the community one lives in affects one’s well-being. People then begin to develop skills for gaining control over relevant aspects of their lives, such as advocating for themselves or working on coping techniques to respond to discrimination. To truly address all the factors that affect a person’s life, people’s actions should also be directed toward changing the conditions of oppression at multiple levels, such as conditions in the home, at work, or in society. These environmental changes can be complemented by an increase in one’s degree of control over aspects of one’s own life.

Psychological empowerment considers the role of the context and the influences from external factors that impact the lives of all people (Keys et al., 2017). For example, women in the 1950s were affected by how they were treated both at home and in the workplace. In both cases, there were clear power differentials, whether it was between husband and wife or employer and worker. These external factors, or contextual factors outside of individual women’s control, impacted women in the environments where they lived and worked. The Women’s Movement and related advocacy efforts were led by women who had developed empowerment skills individually and began supporting the empowerment of others on a societal scale.

Changes individually and on a group level can be accomplished through critically examining the situations people find themselves in. For example, the Black Power Movement in the 1960s and the Black Lives Matter Movement in the present are responses to the personal and societal oppression African Americans felt and feel as citizens of the US. These social movements criticized the cultural norms of the time and challenged people to really think critically about how African Americans were being mistreated and abused on a daily basis. As with all individual and group level change, the context had to be examined through a critical lens.

Critical awareness leads individuals to identify personal and contextual factors that may be part of empowerment for particular individuals or groups. These factors may include additional skills, access to financial capital, access to other resources and opportunities, and access to individuals with greater power. Methods include, but are not limited to, training, developing advocacy skills, studying, becoming self-efficacious, and pursuing resources and opportunities (Cattaneo & Chapman, 2010). By increasing skills and access to resources, one can work towards achieving an increased sense of individual and psychological empowerment. A good example of psychological empowerment is found in Case Study 10.1, about Ed Roberts and his efforts toward helping people with disabilities live independently.

Case Study 10.1

Independent Living Movement

The life of Ed Roberts—a central figure in the development of the independent living movement for people with disabilities in the US—is an example of psychological empowerment. Ed became severely paralyzed at a young age. In his childhood, Roberts’ mother instilled an appreciation for education in her son. She also taught him how to advocate for what he needed. Roberts experienced firsthand the ways in which society distributed power unfairly. A high school administrator threatened to not allow Roberts to earn his high school diploma because Roberts had not completed a driver’s training or physical education course, which he could not physically perform. He had to fight those decisions. After graduating from high school, Roberts was admitted to the University of California-Berkeley but had to fight for accommodations and support from both the university and his rehabilitation counselor. Roberts’ admission to the university drew more individuals with physical disabilities to attend the college. He began to advocate for changes to be made to the physical environment, such as curb cuts to aid people in wheelchairs. He also helped to create the first student-led disability services program in the United States and advocated for attendant services and wheelchair repairs to be provided on campus. At the University of California-Berkeley, he earned both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree. Because of his work, Ed made this university a more accessible place for himself and other individuals with disabilities.

Organizational Empowerment

At the organizational level, it is useful to think of empowerment in two ways: empowering those within the organization, and being effective in fairly addressing organization level issues and working well with those outside the organization such as other organizations and governmental policies and laws. Regarding the first meaning of organizational empowerment, empowering, we can think of ways an organization is empowering those individuals and groups within it. We first need to recognize that organizations can control and influence those who are inside the organization (Peterson & Zimmerman, 2004). For instance, Maton (2008) identified a set of positive core organizational characteristics for empowering community settings. These include a group-based belief system (e.g., the organization inspires change), positive core activities (e.g., active learning), a supportive relational environment (e.g., caring relationships), opportunity role structure (e.g., many roles at multiple levels), leadership (e.g., inspirational vision), and setting maintenance and change (e.g., mechanisms to address diversity or conflict). An organization may foster the empowerment of its members and groups by including these characteristics. An empowered organization also can be effective in working with other organizations and others in the local community and larger society in order to address its needs and meet its goals.

An organization’s ability to empower individuals may be due to interpersonal factors, such as trust. For example, Foster-Fishman and Keys (1997) found that in a large human service organization, employees distrusted system-wide empowerment initiatives set forth by upper management. This lack of trust often reflects perceptions about organizational policies and authority roles. It is important to consider that some organizations are more democratic in the way they operate (e.g., cooperatives) and incorporate more intra-organizational strategies. The way authority and decision making is shared, or not, among employees affects their sense of empowerment. Some organizations try actively to build personal relationships among members and develop greater trust, which provides a better foundation for organizational empowerment initiatives. Regarding the second meaning of organizational empowerment, we can consider ways in which the organization gains and uses enough resources to support its people and activities, For example, a community group advocating for trans rights holds an effective fundraising effort to support its education initiative to include topics of transgender, gender identity and cisgendered prejudice in sex education curriculum in local schools. An empowerment initiative at the organizational level is the focus of Case Study 10.2.

Case Study 10.2

Staff Nurses in Canada

Laschinger et al. (2001) analyzed the impact of organizational empowerment theory on staff nurses in Canada. Results from their study suggested the workplaces that increased perceptions of individual empowerment also increased trust in organizational authority, commitment to organizational goals, and effectiveness of the organization as a whole. The results also suggested an increased work ethic and desire to remain in the organization. This empowerment was facilitated through a number of intra-organizational strategies. First, the nurses were trusted to act on their expertise when performing their work. This was accomplished, in part, by providing nurses access to both timely information and support. Additionally, nurses were given access to resources. Trust can be diminished in an organization if nurses do not have access to medical equipment and supplies or are forced to work overtime due to staff shortages. The researchers also found a relationship (albeit, less significant) between trust in management and opportunities for career advancement. This view of organizational empowerment required that management nurses and staff nurses work collaboratively towards shared goals, in order to better their organization and improve patient care. In order to foster individual empowerment, management nurses exercised less direct control and practiced providing more feedback, support, and guidance. They also worked to ensure trust both among staff nurses and between staff nurses and management. In this case, greater individual empowerment led to greater organizational empowerment.

Community Empowerment

The concept of community-level empowerment has also received attention from community psychologists. Community empowerment means a community has the resources and talent to manage its affairs, to control and influence relevant groups and forces within and outside the community, and to develop empowered leaders and community organizations. One example of developing empowered leaders is community members learning to organize so they can take part in improving their communities and take actions toward these improvements. Empowerment may be particularly important for communities rebuilding after trauma, such as survivors of a natural disaster, or for individuals in a war-ravaged country (Anckermann et al., 2005). Indicators of community empowerment include processes such as collective reflection, social participation, and political discussions, as well as outcomes such as having obtained adequate resources for improving community well-being and social justice (Anckermann et al., 2005). Collective reflection means that community members get together and jointly examine the issues that have mattered to them over time. Social participation and political discussions are ways in which these communities can take the actions needed to empower themselves. Case Study 10.3 demonstrates how community members used empowerment tools in changing the mental healthcare service system in the US.

Case Study 10.3

Mental Health Delivery

Community empowerment has played a role in improving the mental healthcare system in the US. In the 1970s-1990s, mental health service user activists fought for greater individual autonomy and patients’ rights. They did so by developing their community and giving opportunities for community members to participate in decision making. Additionally, they addressed issues that their community faced. For example, they combated unemployment by supporting legislation such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which prohibits workplace discrimination (Masterson & Owen, 2006). For a number of years, many groups representing different facets of the disability community advocated for the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, a major piece of civil rights legislation. This case study places emphasis on mental health/illness. However, the ADA helped all disability groups and individuals with mobility issues were most active in effecting this legislation.

Community empowerment works through increasing the community’s influence over the structures and policies that affect the lived experiences of the community and its members. Increases in influence often occur through partnerships between those in power and other community members. These partnerships may take place in advisory boards, coalitions, or broader community inclusion initiatives (Fawcett et al., 1994). At times, community empowerment may mean that members of the community become empowered with the help of the community leaders and vice versa. Such “co-empowerment” may be challenging, yet can be very beneficial to communities (Bond & Keys, 1993).

Societal Empowerment

Finally, it is important to examine empowerment on the societal level. Empowerment is concerned not only with a psychological sense of control but also with the equal distribution of resources, attention to material, and political empowerment on the societal level (Nelson & Prilletensky, 2010). Even if empowerment interventions are carried out at other levels, they typically must take broader, more structural societal forces into account. These forces include the impact of systemic racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, ageism, or classism over time. Societal empowerment concerns processes and structures affecting the empowerment of individuals, organizations, and communities (for more information on inadequate resource distribution from Habitat for Humanity, click here). An important consideration is to what extent a society fosters equity, or the equal distribution of resources and opportunities, while providing support to those who have less than their fair share of resources.

An empowering society is one that works to distribute resources equitably as well as effectively. Policies and practices that support such equity are critical, as are the voices of individuals, organizations, and communities. Society-wide empowerment is concerned with how well key components of society work, so that everyone has adequate resources. Moreover, society must use resources wisely to address its needs in cultural, governmental, political, business, educational, health, and other major areas of community living. Societal empowerment may take the form of communities supporting and influencing one another and of communities working to promote change in public policy at the state and national levels. Societal empowerment also includes a society’s capacity to influence and work with other societies and to manage its own resources effectively. Empowered societies can take care of themselves. They can work with and influence other societies. They can create positive change with their neighbors and others around the world. In short, many societies face the challenge of helping people who are facing serious limitations in their lives. Rarely, if ever, do these individuals have opportunities to deal with the dehumanizing structures in society that cause such limitations. These challenges are related to histories of oppression, discrimination, or segregation, as well as disparities in income and opportunities that are systemic and very hard to address, as indicated in Case Study 10.4.

Case Study 10.4

Societal Empowerment

Individuals who experience poverty are often in positions of powerlessness due to their lack of access to necessary resources. In order to address the empowerment of individuals in poverty, societies must develop their critical understanding of the structures that create and sustain poverty. After critical awareness is developed, societies must amend or remove the disempowering structures that have been identified. Empowering people who are experiencing poverty can happen through many different means. For example, addressing workplace discrimination through a legislative action is a step towards creating a more equitable society. Additionally, addressing the barriers to participation in the political system is important to address poverty. People who are impoverished may not be registered to vote. Creating accessible opportunities for voter registration can help to ensure active political participation. On voting days, ensuring that people know they have a right to leave work to vote and providing transportation options is another way that societies can support the empowerment of people experiencing poverty.

PRIVILEGE, OPPRESSION, AND EMPOWERMENT

As discussed throughout this textbook, some groups often use their power to accumulate privileges over the groups they oppress. This oppression happens with dehumanization and exploitation, as discussed in Chapter 9 (Palmer et al., 2019). Oppression may occur on any level from individual to societal. It also has a psychological piece. Those in power oppress individuals and groups by reducing their opportunities for education, work, housing, and health care. Then those on the receiving end of this oppression may take part in negative activity due to feelings of hopelessness and helplessness. In addition to the experience of exclusion and marginalization on a societal level, the problem of oppression is compounded when those oppressed engage in self-destructive patterns due to the internal feelings of hopelessness. For more information on how oppression works on multiple levels, click here.

Unfortunately, conditions of exclusion and disadvantage are often ignored when those individuals with fewer resources try to obtain services. Furthermore, the economic inequality of people of color, people with disabilities, and many other groups in the US and other countries, contributes to their limited access to many services and supports. Economic inequality also limits opportunities for employment, housing, health care, and education. These conditions can only be eliminated by changing unequal power relations and with the redistribution of wealth. Attention to the distribution of power and wealth is consistent with the principles of Community Psychology regarding social justice, respect for diversity, and promoting social change, as discussed in Chapter 1 (Jason et al., 2019).

CRITICAL CONSCIOUSNESS

According to Paulo Freire (1970), most people who experience social oppression do not necessarily act to change their reality. This is because they have been taught to accept the dominant, or oppressors’, narrative. That narrative has placed them in an inferior position and their oppressor’s in a superior one. Over time, the oppressed come to believe in their inferiority and thereby internalize their oppression. The inferiority is now a part of their identity and affects the actions they take and the decisions they make in life. In turn, their acceptance of an inferior position in society enhances the dominance of their oppressors. Freire also argues that marginalized individuals do not have a critical awareness that allows them to see the injustices in their lives. They tend to be passive and unable to recognize their own capacity to transform their social realities, in part, because their condition of marginalization and oppression keeps them in a state of helplessness. Someone forced to the margins of society who lacks critical awareness may accept their low position. They may see it as the result of fate, bad luck or supernatural forces. This is why helping people develop critical awareness and understanding of the factors that contribute to their situation is an important early step in the process of empowerment. Once people understand the reasons for their situation and the importance of taking action(s) in order to address their own problems, the process of empowerment has begun. An example of an oppressed group, in this case children, becoming empowered through participatory means is illustrated in Case Study 10.5

Case Study 10.5

School-Based Participatory Action Research

One of the ways in which critical awareness can be developed is through participatory action research. This is a method of research that allows stakeholders to play an active role in determining, assessing, evaluating and addressing a problem. Dworski-Riggs and Langhout (2010) used a participatory action research project in an elementary school to address disciplinary issues during recess. Based on a school survey, multiple stakeholders identified recess as a time in which students had more negative relationships with other students and recess staff. One of the ways in which the issues at recess were addressed was through a peer mediation program. A group of students was trained to resolve conflicts on the playground. This peer mediation program gave students increased control over recess time, as well as increased skills in conflict resolution. Additionally, it empowered the students to meet with the recess staff in order to determine how they could work together more effectively. The researchers did face significant challenges in engaging parents in active participation in the creation and implementation of the intervention. Based on a school climate survey, most parents felt powerless to make changes within the school. However, the students did engage in the process and were satisfied with the outcomes.

A CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF EMPOWERMENT

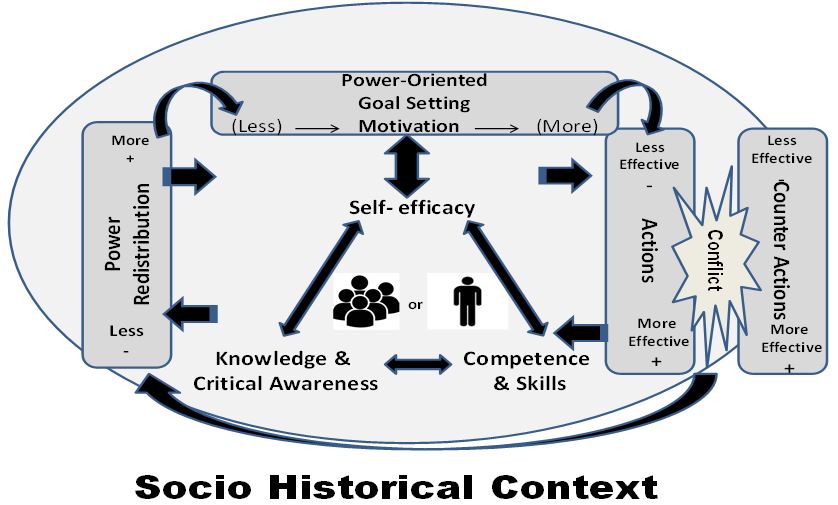

Balcazar and Suarez-Balcazar (2017) offer a model of empowerment that is a framework of analysis for the struggle in the redistribution of resources in a historical context (see Figure 1 above). The model can explain some of the factors that lead people to seek power redistribution, and a redistribution of power is needed to give people the resources necessary for the empowerment process. From this model, it is possible to propose specific strategies that can be used to promote empowerment on the levels we discussed earlier in the chapter. This process is explained further in Case Study 10.6 below.

Case Study 10.6

A Personal People First Story

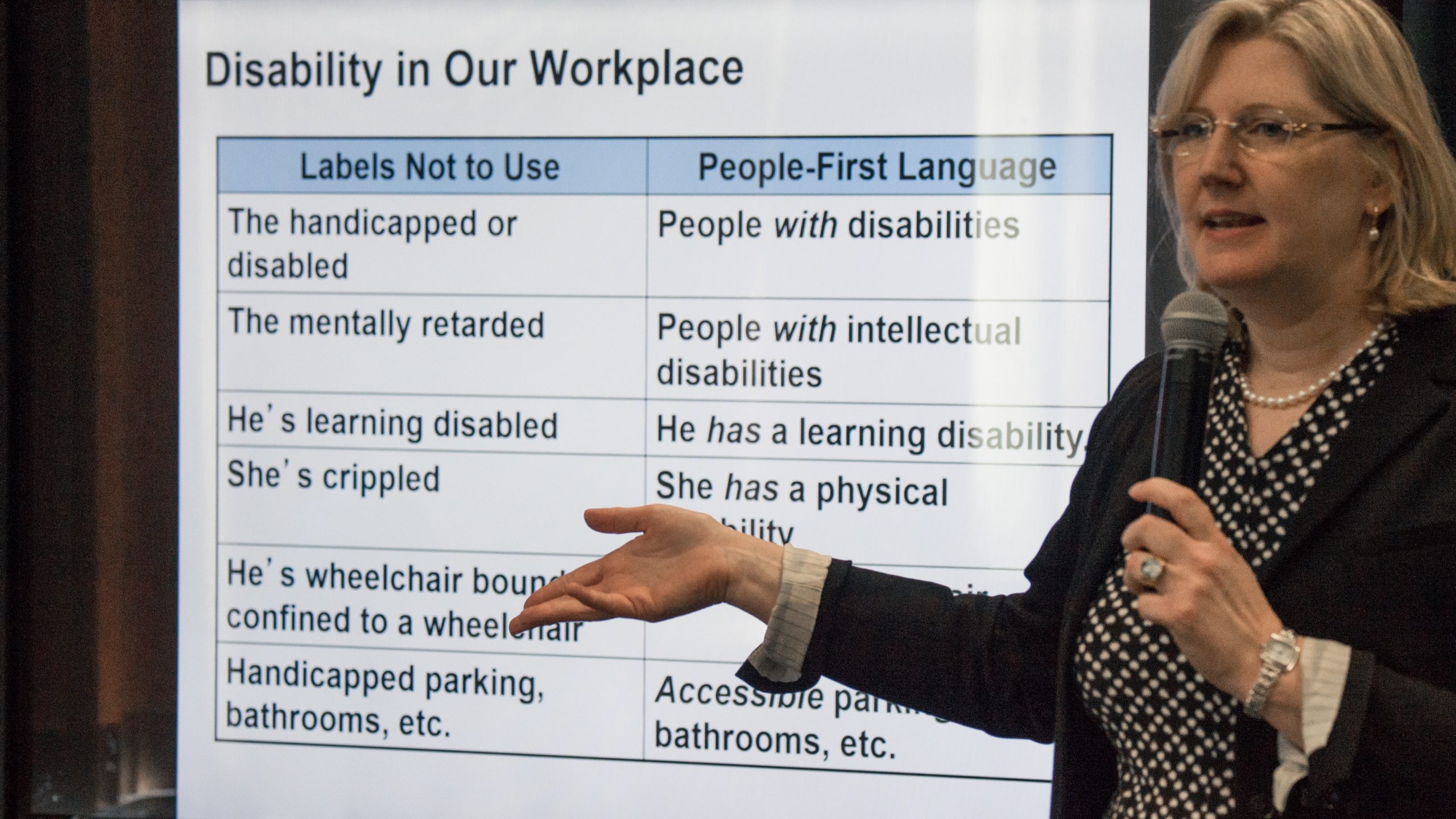

The empowerment process starts when the individual identifies an injustice that she or he has experienced. Joe grew up in a rural town in Missouri to a family with few economic resources. He was born with Down syndrome, and from his earliest memories recalled being stared at, whispered about, laughed at, and treated differently. In an effort to help him, his parents would always decide what was best for him and advocate on his behalf at school and in the community. When Joe tried to speak up and express himself he was either ridiculed by his peers or defended by his parents. As a result of these experiences growing up, Joe felt disempowered and defective. But, he resolved later in life to find others like him and see if he could do anything to change things for people like him. Joe became aware of historical inequalities, injustices, and grievances that have not been attended to, such as the mistreatment of people with disabilities in his rural town. Joe began to network and organize with other people with disabilities, and expanded beyond those with Down syndrome to include other people with disabilities. He recalls being shocked at the number of people he met while trying to form a support network. While networking and researching, he discovered the People First movement, which was formed to promote the sharing of ideas, cultivate independence and friendship, and advocate for people with disabilities. Joe was taken with the ideals of the movement, proudly saying, “We can speak for ourselves, thank you!” By organizing a new chapter of People First, Joe and his peers were able to create advocacy goals to change how they were being mistreated and marginalized in their community.

As shown in Balcazar and Suarez-Balcazar’s (2017) Empowerment model, goals are developed regarding what is desired in a particular situation or context. There are different degrees of motivation associated with the individual’s goal, depending on the circumstances and sense of urgency.

According to this empowerment model, there are several factors that determine the degree of effectiveness of the individual or group in seeking power redistribution. In the case of Joe and his People First chapter, they were a dedicated group committed to influencing the community on multiple levels. They began to petition the local government to offer special accommodations for people with physical disabilities, such as wheelchair ramps and accessible seating on public transit. And, near and dear to Joe’s heart, they advocated for “People First Language Days,” at the local grade schools and high schools. Joe wanted to change how people viewed and talked about disability, to ensure that kids growing up with disabilities were not ridiculed and picked on. Joe thought that if students had more of an awareness of what it’s like to live with a disability, and how hurtful words can be, then attitudes and treatment of people with disabilities might start to change. He wanted members of the community to view him and others like him as “people first, disability always second. Like any other card normal folks have been dealt, it’s just a part of who we are. But we’re just people.” Joe and the People First chapter were successful in their efforts to implement People First Language Days at the schools, and even started having language days in places of business and legislation. Their group possessed factors necessary to implement meaningful change and empower not only themselves but many others like them in their community. These factors included knowledge of rights and responsibilities, level of skills and degree of self-efficacy (as well as the result of cumulative experience, challenges, and successes) in attaining personal and group goals.

What can be unexpected when working in Community Psychology are the counteractions taken by the opposing individual, group, or organization. There were some people in Joe’s town who opposed using taxpayer funds to increase accessibility for people with physical disabilities. Some educators questioned the need for having time taken from their classes to educate students on People First language. Sometimes the individual or group runs out of options, exhausts their resources, or gets demoralized and concedes defeat. There is no guarantee that the process will result in greater power to the aspiring individual or group. It takes time to empower oneself and to empower a group of people, and there may be setbacks before achieving meaningful power redistribution. The resulting changes in power redistribution may stop the process if the parties are satisfied, meaning the person or group aiming for empowerment feels they have achieved their goals. At some future point, the parties may resume the process in order to pursue better results.

As mentioned earlier, the Women’s Movement of the 1950s and beyond led to great strides for women in America, and the “Me Too” movement is another call for women to receive fair treatment and justice in society. Balcazar and Suarez-Balcazar’s (2017) Empowerment Process Model is cyclical, meaning individuals or groups may seek more knowledge or advocacy training or critical awareness of the members in order to succeed. The individual’s sense of efficacy is affected by the degree of success in conducting these efforts over time, which in turn can lead the person to try to seek empowerment in other situations.

TACTICS FOR COMMUNITY ACTION

Along with the empowerment model presented here, individuals may use a variety of strategies to address power imbalances (Fawcett et al., 1994). These strategies can help reduce or eliminate barriers, develop networks, and educate others in the community (see Practical Application 10.1). They can also create opportunities for capacity building and allow participants to advocate for changes in policies, programs, or services. To promote empowerment at the environmental and societal level, it is important to examine national, state, and local policies. Many programs and services unexpectedly place barriers and stressors on oppressed groups, such as people with disabilities. Ultimately, empowerment efforts are directed at promoting social justice. The strategies highlighted in this chapter can serve as a guide for individuals interested in promoting empowerment in their communities. It should be noted that there are many tactics that have been used to promote change over time. For example, Sharp (1973) researched and catalogued 198 methods of non-violence actions to promote social change and provided a rich selection of historical examples of the tactics.

Practical Application 10.1

Examples of Advisory Tactics

The tactics below help in thinking about the best approaches to advocacy. Each tactic is supplemented by a real-world example that can help you think of ways to advocate in your community.

Tactics for Understanding Issues

- Gather more information:

A group of concerned family members interviews the staff and clients at a local group home to investigate claims of client neglect. - Volunteer to help:

Volunteers from the local Alliance for the Mentally Ill (AMI) are making efforts to contact the parents of youth who are hospitalized to introduce the services of the organization and offer their support. These volunteers often help these parents talk about their feelings regarding their family’s situation.

Tactics for Public Education

- Give personal compliments and public support:

A member of a local student organization sends a letter of support to their member of Congress who co-sponsors a bill which would prevent workplace discrimination against individuals who are part of the LGBTQ+ community. - Offer public education:

A group of college students organizes a performance which depicts institutionalized racism in American society. They perform this show at high schools in their home state.

Tactics for Direct Action

1. Making your presence felt

- Express opposition publicly:

A student at a local university writes a blog about unfair wages for student workers. - Make a complaint:

An employee notifies the human resources department after seeing an instance of sexual harassment.

2. Mobilizing public support

- Conduct a fundraising activity:

A local service provider holds an annual theater benefit to help individuals who are living with HIV/AIDS. - Organize public demonstrations:

A group of service providers is angry with the proposed decrease in funding for home services. They organize a sit-in with their group home residents, their family members, and other interested community members on the steps of the State House Building.

3. Using the system

- File a formal complaint:

A person in a wheelchair files a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission because the place where she works lacks accessible bathrooms. In her written complaint, she cited the Americans with Disabilities Act, which requires organizations to adapt their buildings to accommodate people with disabilities. - Seek a mediator or negotiator:

A parent has a child with disabilities who is just starting school. She comes to the first Individualized Education Plan (IEP) meeting with an experienced parent who has attended many such meetings at the school.

4. Direction action

- Arrange a media exposure:

A local teacher union uses social media sites in order to share their stories of workplace injustices and economic instability. - Organize a boycott:

A group of college students organizes a boycott of organizations that practice unfair labor practices in order to ensure cheap products.

SUMMING UP

A fundamental principle of Community Psychology is that individuals have the right to live healthy and fulfilling lives, regardless of their ability levels, gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, income, or other characteristics. A person’s well-being depends on personal choices and the dynamic interaction between individual and environmental factors. Community psychologists support the most vulnerable groups of society in their quest for justice and equality. We can work with historically oppressed groups as they claim their rights and their own personal and cultural identities. Research and advocacy efforts must continue until full participation in society has been achieved.

Community psychologists are continually working to refine the effectiveness of empowerment and advocacy efforts. In this chapter, we have provided definitions and successful examples of empowerment and identified some of the strategies, predictors, and facilitators in our efforts to achieve power redistribution. Consistent with an ecological approach, community-based participatory research methodologies help us include the voices of historically oppressed groups in our research and advocacy efforts. Partnering with historically oppressed groups allows us to better understand oppression and allows us to work toward developing effective ways in which they can gain power to address their unmet needs. Our goal is to work toward a more fully empowered and empowering society and realize the promise of equity and quality of life for all. This ongoing commitment will continue to propel our social and community change efforts into the future!

Critical Thought Questions

- Where do you feel disempowered in your life? What makes you feel this way?

- What are the tangible steps that you can take in order to gain more power? What skills can you gain? How can you increase your critical awareness?

- Think about an issue that is occurring in your community. What are tactics that you can employ in order to address the issue? What group(s) would be important for you to partner with in order to be more effective?

Take the Chapter 10 Quiz

View the Chapter 10 Lecture Slides

____________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Anckermann, S., Dominguez, M., Soto, N., Kjaerulf, F., Berliner, P., & Naima-Mikkelsen, E. (2005). Psycho-social support to large numbers of traumatized people in post-conflict societies: an approach to community development in Guatemala. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 15(2), 136–152.

Balcazar, F. E., & Suarez-Balcazar, Y. (2017). Promoting Empowerment among Individuals with Disabilities. In M. A. Bond, C. B. Keys & I. Serrano-García (Eds.). APA Handbook of Community Psychology (Vol. 2, p. 571-585). American Psychological Association.

Bond, M. A., & Keys, C. B. (1993). Empowerment, diversity and collaboration: Promoting synergy on community boards. American Journal of Community Psychology, 21, 37-57.

Cattaneo, L. B., & Chapman, A. R. (2010). The process of empowerment: A model for use in research and practice. American Psychologist, 65(7), 646–659.

Dworski-Riggs, D., & Langhout, R. D. (2010). Elucidating the power in empowerment and the participation in participatory action research: A story about research team and elementary school change. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3), 215-230.

Fawcett, S. B., White, G. W., Balcazar, F. E., Suarez-Balcazar, Y., Mathews, R. M., Paine-Andrews, A., Seekins, T., Smith, J. F. (1994). A contextual‐behavioral model of empowerment: Case studies involving people with physical disabilities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 22(4), 471–496.

Foster-Fishman, P. G., & Keys, C. B. (1997). The person/environment dynamics of employee empowerment: An organizational culture analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 25(3), 345-369

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum Publishing Company.

Jason, L. A., Glantsman, O., O’Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. (2019). Introduction to the field of Community Psychology. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/intro-to-community-psychology/

Keys, C., McConnell, E., Motley, D., Liao, C., & McAuliff, K. (2017). The what, the how, and the who of empowerment: Reflections on an intellectual history. In M. Bond, I. Serrano-Garcia, & C. Keys (Eds.). APA Handbook of Community Psychology: Theoretical Foundations, Core Concepts, and Emerging Challenges (Vol. 1). American Psychological Association.

Laschinger, H. K., Finegan, J., & Shamian, J. (2001). The impact of workplace empowerment, organizational trust on staff nurses’ work satisfaction and organizational commitment. Health Care Management Review, 26(3), 7-23.

Masterson, S., & Owen, S. (2006). Mental health service user’s social and individual empowerment: Using theories of power to elucidate far-reaching strategies. Journal of Mental Health, 15(1), 19-34.

Maton, K. (2008). Empowering community settings: Agents of individual development, community betterment and positive social change. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 4-21.

Nelson, G. B., & Prilleltensky, I. (2010). Community Psychology: In Pursuit of Liberation and Well-Being (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Palmer, L., Ferńandez, J. S., Lee, G., Masud, H., Hilson, S., Tang, C… Bernai, I. (2019). Oppression and power. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/oppression-and-power/

Peterson, N. A., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2004). Beyond the individual: Toward a nomological network of organizational empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34(1), 129–145.

Rappaport, J. (1981). In praise of paradox: A social policy of empowerment over

prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9(1), 1-25.

Sharp, G. (1973). The Politics of Nonviolent Action (3 Vols.) Porter Sargent.