14

Mayra Guerrero; Amy J. Anderson; and Leonard A. Jason

Chapter Fourteen Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand how public policy interventions can bring about impactful change

- See how social justice issues can be addressed through public policy

- Identify ways you can get involved in public policy

Maria had to take out thousands of dollars in student loans to afford college tuition, and then she had to spend a large percentage of her post-graduation income paying off those loans. This is not an unfamiliar story, and more and more college students face this situation. In fact, millions who attended college seeking an education and a better life now face crippling student loan debt. For example, in the US, student loan debt totals $1.5 trillion dollars, increasing by nearly 400% in the last 30 years and more than tripling since 2005. This loan crisis is now causing financial strain to many who are trying to repay their student loans, disproportionately impacting low-income students of color (Miller, 2017).

This chapter is about policies that often are not visible but create these types of hardships, and it will often take a historical perspective to see the reasons so many have diminished life opportunities and long-term financial hardship. Let’s examine some of the public policies that have caused this problem. Tuition costs for both public and private institutions have risen, state investments in higher education have been reduced, and many student loans are now privatized. The solution to the student loan problem will require policy changes such as increasing grant aid awarded to low and middle-income students, and passing legislation that would make tuition more affordable. Even more daring and bold policies are being tried such as waiving tuition costs entirely. In 2018 New York University’s School of Medicine began waiving tuition fees for all students in an effort to ease both student debt and the ongoing physician shortage. Kaiser Permanente’s new medical school will also be free to attend. Other academic institutions are trying to reduce or eliminate tuition by asking students to pay the schools a small amount of their earnings following graduation. These are examples of real policy interventions that can help revolutionize the problem of excessive student debt.

But there are other ways that we can make a difference as community psychologists. For example, offering free online college textbooks is another way of lowering economic burdens that students encounter at school, indicated in Case Study 14.1.

Case Study 14.1

Free Online Textbook

When the DePaul University Library surveyed students about the impact of textbook affordability on their education, almost 1,000 students completed the survey within the first week. Many students indicated that the cost of textbooks was negatively affecting their lives. Students reported choosing not to purchase textbooks or purchasing them later in the quarter. Of those who did not purchase a textbook, 41.6% cited cost. 56% of the respondents were in their first two years at DePaul and reported receiving a poor grade because they could not afford the textbook for their course. The authors of this book decided to try to make a small difference by developing this free online textbook (Jason et al., 2019), which we hope will help to reduce this economic burden on our undergraduates taking an introductory course in Community Psychology. We consider this very consistent with the values of our field. The authors also worked for almost two years developing a Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA) “Student Associate” free membership status for undergraduates, and this is very much within the tradition of second-order policy change by lowering barriers to active participation in SCRA.

When our new free textbook was introduced in a Community Psychology course at DePaul University, the immediate reaction was very positive (the students uttered a collective sigh of relief) as they mentioned how grateful they were for not having to purchase it. A typical reaction was “This is wonderful, a free textbook!” Our work with this textbook is part of a larger movement to provide textbooks free, online, and available to everyone, and this movement is growing every day. These types of very real structural changes really can make a difference. In this chapter, we will provide an overview of what public policy is and how community psychologists engage in this work to address the underlying roots of the problems we face. This chapter will also provide ways you can become involved with public policy.

WHAT IS PUBLIC POLICY?

Almost every aspect of our lives is impacted by public policy. Public policy is broadly defined as the laws, regulations, course of action, and funding priorities issued by the government to address a social issue at the local, state, and national levels. Essentially, social change often requires the development of a new policy or the revision of an existing policy. Public policies can address societal issues in different areas, including education, healthcare, housing, mental health, immigration, and crime. Policies in these areas can have a far-reaching and long-lasting impact on individuals and communities. Policies also vary in scope. For instance, the legalization of same-sex marriage, how much funding is allocated towards public libraries and colleges, and even what is served for lunch at public schools are all examples of public policy.

National and state-level public policies enacted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic allows us to observe in real-time how public policy can impact people’s wellbeing and safety. In the US, states that implemented strong virus mitigation policies such as encouraging vaccinations, mandating face masks in public settings, mandating stay-at-home orders, and enforcing non-essential businesses’ closures during the pandemic’s peak have helped lessen the spread of the virus. On the contrary, COVID-19 cases and mortality rates are highest in states like South Dakota that have implemented little to no virus mitigation efforts. Countries like New Zealand and Taiwan who implemented extensive restrictions early on, such as robust testing and contact tracing programs and strong mask mandates, have successfully reduced and eliminated new COVID cases.

The impact of policies can also transcend nations by having a global effect. Countries with environmental policies that fail to regulate the use of resources and reduce pollution are making the world less habitable for everyone. The burning of fossil fuels – such as oil, natural gas, and coal—increases greenhouse gas emissions which causes the earth’s climate to rise to warmer than normal temperatures. The solution to this problem will require new policies that will cause countries to switch from using fossil fuels to using greener and more renewable sources of energy (such as solar or wind power). Some may wonder if we can ever be successful with such a daunting goal. Well, others have realized their dreams, such as Mahatma Gandhi who repeatedly confronted the British-controlled government with acts of civil disobedience to bring about freedom for India. The struggle to gain India’s freedom took a long time, and this long-term perspective is often needed to deal with the many policy actions that are causing current problems such as climate change.

Policies created to address specific social issues can either be effective or ineffective. One example of an effective policy is The Housing Choice Voucher Program created to address the lack of affordable housing for low-income households and homelessness by providing rent subsidies. This program has proven to be highly effective in reducing and preventing homelessness and helping low-income families remain housed (Wood et al., 2008). On the other hand, mass incarceration as a means to deter drug use is an example of an ineffective policy. As indicated in Chapter 1 (Jason et al., 2019), the war on drugs (which has led to increased use of harsher drug laws) and three-strike laws (which result in life sentences for drug offenses) have proven to be ineffective in preventing drug use. Rather, these policies perpetuate the incarceration cycle among those with substance use disorders.

Through research and advocacy, community psychologists have directly influenced public policy to produce second-order change. The work on subsidized housing programs is one way to end homelessness. Another Community Psychology example involves work with Oxford House, described in Chapter 1, where over 20,000 people today live in these democratic, self-governing homes. Yet there are communities that oppose sharing their neighborhoods with group homes for people with disabilities or substance use disorders. For example, some cities have tried to pass laws that make it illegal for more than five unrelated people to live in an Oxford House—and this deliberately targets recovery homes which usually need six to ten house members to make rent affordable. Case Study 14.2 is an example of working at the judicial level in order to preserve access to affordable housing for those with substance use disorders.

Case Study 14.2

Not in My Backyard

Leonard Jason was called by a lawyer who asked for help with a dispute involving a town trying to close the local Oxford House recovery home by passing legislation whereby no more than five unrelated individuals could live in one home. But small homes of this size are very difficult to sustain as there are too few people to pay for the house expenses. This is an example of Not in My Backyard thinking, where some community members try to exclude those in recovery homes from their neighborhoods. Jason quickly looked into a national Oxford House data set and examined how the number of residents in Oxford House affected residents’ individual outlooks for recovery. He and his research team found that larger house sizes, of eight or more residents, actually had less criminal and aggressive behavior than houses with fewer residents. The findings were influential: they were used in this court case and others to successfully argue against closing larger house size Oxford Houses (Jason et al., 2008). The founder of these Oxford Houses, Paul Molloy, sent this note to Jason regarding one judicial case that was resolved with the help of these data: “The dispute has been ongoing for six years! The town will pay attorney’s fees, which are about $105,000 and a fine to the Department of Justice. The key to their decision appears to be your research showing that larger houses had better outcomes than the smaller ones. Thanks. Once again reason and logic prevailed.”

When involving yourself with public policy, it is possible to make a difference, as Case Study 14.2 shows. The following sections provide an overview of the many ways in which community psychologists can influence public policy.

COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY AND PUBLIC POLICY

Efforts at the public policy level have always been at the forefront of the efforts of community psychologists to address social issues. Work at this level is considered a core competency for Community Psychology practice and is described as the ability to develop effective working relationships with policymakers, elected officials, and community leaders (Dalton & Wolfe, 2012). To meet this competency, community psychologists are trained in a variety of skills including how to write brief statements used to influence politicians, how to translate research findings into policy recommendations, how to build advocacy coalitions with various community organizations, and how to develop good communication and relationship-building skills. The ecological model so well described by Kelly (2006) provides a theoretical base for these types of activities.

Public policy interventions often focus on a second-order/systems change approach to address the systemic issues such as the inequitable distribution of resources. Importantly, Community psychologists value involving individuals affected by an issue in the policy formulation and implementation process.

Often work at the public policy level involves prevention. Community psychologists have worked in public policy at the local, state, and national levels, in the areas of substance abuse prevention, school violence prevention, and HIV/AIDS prevention. As an example, Case Study 14.3 describes policy work that has focused on social-emotional learning to enhance positive youth outcomes.

Case Study 14.3

Social-Emotional Learning in Schools

Students within K-12 educational settings can be supported through policies and programs that promote positive youth development and prevent negative outcomes. One example of an effective prevention program developed and implemented involves social-emotional learning, which equips students with tools to set and achieve goals, handle their emotions, interpersonal relationships, and life events, and to engage in responsible decision-making. A leader in this field is the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, which has been working to extend programs involving social and emotional learning to school children for more than two decades. This organization, founded by community psychologist Roger Weissberg, collaborates with leading experts and supports districts, schools, and states nationwide to drive research, guide practice, and inform policy. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning supports federal efforts to increase funding for research and evidence-based practice related to social and emotional learning. Through their Collaborating States Initiative, they work with 25 states to support social and emotional learning, and all 50 states have incorporated this approach into their preschool standards; a growing number are doing the same for grades K-12. Learn more by viewing their State Scan Scorecard project, Emerging Insights Report, and extensive CSI resources.

Understanding the Policymaking Process

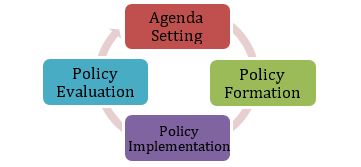

There are four stages of working on public policy. They involve (1) agenda setting, (2) policy formation and adoption, (3) policy implementation, and (4) policy evaluation and revision. The figure above illustrates the cyclical nature of these stages in the policymaking process. Moreover, each phase requires attention to relationships and communication amongst diverse stakeholder groups. Groups involved in public policy include the government advocacy organizations, citizens, and media (as will be indicated below), but first, let’s define these four phases.

(1) Agenda setting. During the first phase of the policymaking process, it is important for those who set a policy to take a particular issue seriously. If, for example, the public officials do not think that climate change is of importance, they will devote little of their time and energy to this issue. So, the agenda-setting phase involves determining whether people with power and influence care about a particular issue. As there are many social problems that may exist in a community or society, only a select number of them might get on the agenda and receive attention for possible action. It is important for community psychologists to work toward bringing attention to an issue so that others will care about it in order to devote time and resources toward improving the situation.

Kingdon (1995) described the process by which a pressing social issue makes it on the policy agenda as three influential “streams.” First, the problem stream involves the range of social issues that may affect a given population, ranging from high levels of unemployment and low levels of available housing, to rates of drug addiction and homelessness within neighborhoods. For example, if a problem affects many people, it is more likely to secure some attention. Second, the policy stream embodies potential solutions that can address each of these social issues, and of course the costs of these solutions. If there are some practical and affordable solutions to the problems, it raises the likelihood of people willing to consider these issues. Lastly, the political stream involves the level of public concern to actually devote time and resources to one of these topics and possible solutions. If the public is more concerned, the topic is more likely to receive attention.

(2) Policy formation and adoption. In the second phase, a solution to address the social issue is adopted. As an example, if inadequate funding for public schools is agreed upon as an issue needing attention, the politicians could pass laws that channel more funds to schools. The primary places where these types of actions might occur are in legislative bodies, in which elected officials vote on laws.

But policies can also be adopted at the executive level by someone in a high position, such as a president or mayor of a city. A president can create a policy through executive orders, such as the “Travel Ban“(E.O 13769), which tried to limit the ability of individuals wanting to travel to the US. In addition to a president, agencies within the executive branch can adopt policies. For example, the Department of Housing and Urban Development is an executive agency that has been able to move resources into Housing First, which was described in Chapter 1 as an important solution to the homelessness problem in the US.

(3) Policy implementation. Once a policy is adopted, there are many different ways it can be implemented. A well-thought-out policy can be adopted but if limited or inadequate funds are provided for it to be carried out, it is unlikely to have any effects. For example, a prevention program introduced into a school classroom might be compromised and much less effective if the school district has policies that result in inadequate funds being provided for books and other resources needed to implement the prevention program.

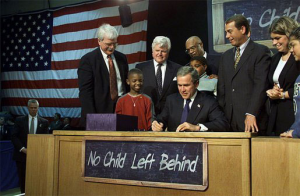

(4) Policy evaluation and revision. The last phase of the policy process is the policy evaluation and revision phase. During this phase, an effort is made to determine if the policy had its intended outcomes and whether it can be improved to more effectively address the social issue. The policy might need to be replaced with an improved policy or terminated in its entirety. For example, the No Child Left Behind Act aimed to address educational inequity by increasing the government’s role in holding schools accountable for the academic progress of their students. This law put an emphasis on standardized testing by implementing frequent assessments measuring students’ educational improvement and rewarding the schools with the highest assessment scores. No Child Left Behind was found to have unintended consequences such as placing too much emphasis on testing, and it even resulted in some school closures. There are now efforts to revise and even replace this set of policies.

Overall, this policymaking process is cyclical and recursive in nature. As demonstrated by the descriptions of the four phases, there are several points in the policy process through which community psychologists can engage in policy efforts. The ways in which community psychologists engage in this cyclical process are discussed in the next section.

HOW COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGISTS INFLUENCE PUBLIC POLICY

Roles and Settings

Community psychologists can influence public policy at any step of the policymaking process by working alongside or within advocacy groups. Advocacy groups, community psychologists, community members, and policymakers are all involved in these policy decisions. Some of the key players on the policy front can be large intermediary organizations such as professional membership organizations, foundations, and research and evaluation firms. For instance, community psychologists can work with Mathematica or the Urban Institute, which are research and evaluation firms that are hired by federal agencies to conduct policy evaluations. Foundations like the William T. Grant Foundation also provide opportunities to engage in policy work, given their focus on funding policy initiatives that address social issues that are important to community psychologists. In fact, the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, which was described in case study 14.3 was begun by a grant from the William T. Grant Foundation, described in this article. Community psychologists also work with other types of advocacy organizations including member-led social action groups (e.g., Black Lives Matter) or even small informal groups (e.g., a group of students and teachers advocating for funding for afterschool programs).

SCRA is one example of an intermediary organization that is the central professional home of many community psychologists. This organization is open to researchers, practitioners, and students (and as stated in Case Study 14.1, you can be an Associate Student member at no cost). Advocating for federal and legislative policies that promote social justice is an important goal of SCRA. This organization issues policy statements to take public positions on social issues, offers research and scientific evidence that support their positions, and provides recommendations to policymakers and other stakeholders. The first public policy statement SCRA released was on the role of recovery homes in promoting long-term addiction recovery and can be viewed here. SCRA also releases rapid responses, which are public stances and action plans on policy issues that are time-sensitive and require immediate action. In addition, SCRA has a Public Policy Committee, which provides members with resources and training to facilitate their policy involvement.

Many community psychologists are engaged in policy advocacy work as researchers within universities. As faculty members, community psychologists are able to contribute to policy in many different ways. For example, Community Psychology faculty can develop expertise in a given policy area, generate research findings with specific policy implications and recommendations, advocate for policies that are empirically supported, and work as policy consultants for advocacy organizations like the ones described above. Most of all, university faculty educate students on policy-relevant issues and provide ways they can become involved in policy advocacy.

In addition, community psychologists can work as policy insiders within local, state, and federal levels of the government. Policy roles within the government can be obtained through direct election, appointment by an elected official, or by obtaining employment as a civil servant. Some examples of these roles include working as a congressional staffer or working as a member of a local school board. Working as policy insiders within the government allows community psychologists to oversee policy implementation and possibly the creation of new legislation.

Methods for Influencing Public Policy

There are several methods through which community psychologists can work in public policy. The following methods may be used throughout the four stages previously discussed of the policymaking process:

Research. As mentioned earlier, research is a key tool community psychologists use to influence policy and there are different types used to influence policy (National Academy of Science, 2012). One of these ways is conceptual research, which is used to educate policymakers and stakeholders on social issues and propose possible solutions. Community psychologists often use this type of research to help policymakers view a social issue as a systemic problem caused by ineffective and harmful policies rather than individual deficits. Such research has been used to show how segregation leads to increased stigma for those being excluded from the mainstream. A prime example of how conceptual research influenced policy is the historic US Supreme Court’s decision in Brown vs Board of Education, which led to the desegregation of schools. Conceptual research by psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark (1947) demonstrated the harmful psychological effects of segregation, which was cited by the Supreme Court as having played a crucial role in their decision that racial segregation of schools was inherently unethical and unconstitutional.

Instrumental research can be used to persuade policymakers to adopt a policy. Over the past few decades, the disability community has used policy interventions to bring about major changes to the ways that individuals with disabilities can have greater access to opportunities. These include altering pavements and curbs at intersections so they allow people in wheelchairs to safely navigate through them, and providing individuals with movement disabilities access to buildings, public transportation, and parking spots (Jason & Jung, 1984).

Consultation. Community psychologists often act as consultants in public policy by sharing their research and advocacy expertise with organizations or governmental agencies. This often begins when community psychologists develop personal relationships with policymakers and government officials. Consultation is a way of influencing policy (Block, 2006) by providing policymakers with relevant evidence and data. Community psychologists, during the consultative process, have been instrumental in providing content-level expertise on current efforts to reduce human trafficking and to condemn hate and terrorism by white supremacists.

Program evaluation. Evaluation is important across the policymaking process, but particularly within the policy implementation and evaluation stages. In evaluation, community psychologists might aim to examine whether a social program works well, who it works well for, under what conditions it works well, and whether it can work better (Miller, 2017). For example, the Meals on Wheels program delivers meals to older adults in need to help with their nutrition as well as reduce their isolation. Evaluations of this program have found a number of positive outcomes for meal recipients, and the findings from the evaluations have been used to make the programs even more effective.

Coalition-building. Community psychologists also use their communication and relationship-building skills to form community coalitions with community members, organizations, and policymakers. Members of a coalition share a common policy interest and agree to work together to influence or develop a public policy. Forming and maintaining coalitions is an effective way to influence policy. Nelson Mandela, imprisoned for decades in South Africa, inspired coalitions to continue their activist work, and these coalitions were eventually successful in abolishing the system of apartheid.

Media and written communication. Community psychologists use a variety of communication methods to influence public policy. For example, they can share knowledge as guests on multimedia outlets like news radio, television, or podcasts. More commonly, community psychologists can influence policymaking decisions through written communication in “white papers.” These concisely provide scientific evidence and recommendations directly to those in decision-making positions. Communication strategies vary depending upon the audience. For example, appearances on podcasts and public radio could be used to target voters in order to garner support for a public policy issue. Providing “white papers” to congressional officials, on the other hand, requires concise written language with straightforward suggestions that are sensitive to the policymakers’ busy schedules. When coal miners had been killed by negligent mining practices, white papers and publicity surrounding their deaths led to better laws and regulations. These types of tragedies have been used to highlight and bring attention to abuses of power, which have been used by policy activists to change the status quo and bring about social justice. Another example is Rachel Carson’s influential book Silent Spring, which powerfully identified abuses in the use of pesticides and helped start the global environmental movement.

Selecting a Policy Issue and Developing a Plan for Action

There are many ways in which students and community psychologists can get involved with public policy. Below are some practical suggestions:

Choosing an issue to advocate for. There are many social issues that require advocacy and many social issues with which we may be interested in getting involved. Before getting involved in public policy work on a particular issue, it is important to examine which issues are most aligned with your interests, skills, and access to resources like time, funds, materials, or energy. One way that you can examine your competencies related to an issue is through the Advocacy Self-Assessment (Jason et al., 2015).

Practical Application 14.1

Advocacy Self-Assessment Tool

To complete the self-assessment in this activity box, first consider several social issues with which you are interested in engaging in advocacy work. Once you have selected the social issues, complete the self-assessment questions for each social issue. Then, total up your scores for each issue to determine which received the high score. This will help you determine what you are most passionate about.

Using the range below, rate your agreement to each question for each of your chosen issues. Once you have determined which social issues might best fit your advocacy competencies and commitment, consider making a plan for your involvement. For the issue you score highest on, develop a plan to advocate directly and indirectly to initiate social change through policy.

1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither Agree/Disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree

COMMITMENT

- Are you strongly committed to working on this issue?

- Are you willing to put in a great effort to achieve this goal?

- Would you be willing to spend many years working on this issue?

- Do you have a sense of obligation to continue working on this issue above all others?

CENTRALITY

- Is what you have listed more important than any other issue you could work on?

- Is this a matter of great personal meaning to you?

- Do you have a passion and a burning desire to see this issue dealt with?

- Is this an issue that you devote a lot of time thinking about?

RESOURCES

- Are you a member of or do you work with any activist groups or community organizations that are dealing with the topic you have selected?

- Are you aware of any friends, family members or colleagues who are either working on this issue or interested in doing so?

- Do you have access to resources (time, energy, funds, materials) that might be applied to working with this topic?

- Do you feel that you have the capabilities and confidence to engage in work with the issue that you have mentioned?

Stay informed. Listen to the news and stay informed of current events occurring both locally and at a national level. This could even include following current bills and resolutions being presented before your city council or congress, procedures to be implemented by executive offices (e.g., Department of Education), or cases to be heard before the Supreme Court. A useful tool is the GovTrack website, which shows where bills and resolutions are within their legislative process.

Contact policymakers. There are several ways in which you can communicate with policymakers at all levels of government. Federal elected officials have offices in your cities and towns, as well as in Washington DC, to whom you can write letters or make phone calls. Similarly, state elected officials can be reached by phone and by mail at their neighborhood or state offices. Another way to interact with policymakers is through social media (e.g., Twitter) or through email in which you can express your concerns and opinions about ongoing legislation. You can find out who your elected officials are by visiting this website. A helpful resource for contacting elected officials is Resist Bot (which automates faxes and messages from your cell phone).

Policy and advocacy organizations. There are many opportunities for getting involved with existing policy organizations. If you have an interest in a particular social issue, such as rising economic inequalities, you can find local and national organizations that are focused on that work. A good way to get informed is to ask to be listed on an organization’s email list and follow them on social media. Getting connected to organizations may allow for engagement through events, town halls, or event Capitol Hill days in which organizations arrange visits to legislative offices to speak with policymakers. Furthermore, students may also explore working with the organization through volunteer or internship positions.

Public Policy and Structural Inequality:

Public policy can also be used to enforce inequality across communities. Structural Inequality defines the condition in which a group’s unequal status is maintained by the reinforcement of unequal decisions, rights, and opportunities afforded to them. The word “structural” emphasizes that these inequalities are rooted in dominant social institutions’ daily operations such as health care, education, government, and housing. Those who wish to keep oppressive power dynamics within these institutions can achieve this goal by enacting discriminatory policies. Policies are then used as a mode to silence, isolate, and victimize vulnerable groups in the interest of preserving the social order prescribed by those wielding social power. When these policies go unchallenged, they perpetuate the suffering experienced by the oppressed. Community Psychologists in public policy can work to curtail these outcomes and advocate for disadvantaged social groups.

In 2020, a global uprising emerged lead by the Black Lives Matter movement. The protests erupted from a widely shared video of the fatal interaction between a former Minnesota police officer, Derek Chauvin, and a Minneapolis resident, George Floyd. Floyd was an African American man who in the video is pinned to the ground by Chauvin using a method in which the knee is pressed firmly against the neck. In the moments before Floyd died, he is heard crying out, “I can’t breathe”. The video illustrates the disturbing reality of policing that targets Black men and the high level of complacency to their deaths. Allies across the world passionately called for justice and began conversations regarding the history of policing that led to the modern unjust treatment of Black men in the law’s hand. Dating back to their origins, police departments were put in place to primarily protect White citizens (Archbold, 2012). The racist ideologies which structured policing and the preservation of segregation continued in public policy decisions made over the decades (e.g., redlining, the war on drugs, tough-on-crime policies/the “Superpredator” theory, and the deputizing of local authorities to enforce immigration laws through racial profiling).

What began as a call to reform police departments soon grew into demands to defund or totally abolish the police altogether. Communities found that first responders equipped to address issues like mental health, housing insecurity, and domestic violence were likely very beneficial to their safety and deserved adequate funding to efficiently operate as accessible community resources. These community resources could then take over some functions of the police while maintaining citizen safety. Some cities have already begun to defund their police departments to apply this idea. One example being New York City, which slashed $1 billion from the city’s 2021 budget and reallocated funds to mental health, homelessness, and education (McEvoy, 2020).

CHALLENGES TO POLICY WORK

Engaging in policy work is not easy. There are many challenges that community psychologists often will need to overcome when attempting to influence policy. A major challenge in policy advocacy is that it can take many years before a policy is adopted, implemented, and revised. The key lesson learned by community psychologists is to stay committed to a social issue for the long run. Another major challenge community psychologists face is navigating issues of power when working with policymakers and advocacy organizations. For example, powerful stakeholders with different vested interests may actively try to stand in your way. Policy work requires effectively navigating these challenges.

The topic of school shootings illustrates all these complexities. For example, does the community find this topic to be a pressing issue? Concern for school shootings may arise from public feedback or an event related to the issue. For example, school shootings may be perceived as a more pressing social issue directly after a shooting occurs in a community. Many solutions may be proposed and compared with one another. These solutions offered for school shootings have included the restriction of access to weapons, increasing school security personnel or procedures, and some have even advocated increasing access to guns by teachers. Further, the costs, feasibility, and availability of evidence for each of these solutions need to be evaluated as potential policy solutions. Finally, issues of partisanship can emerge. For example, membership in the Republican or Democratic party may influence how receptive a policymaker is to consider a plan to address school shootings. Moreover, broader cultural and societal moods about guns and school violence can influence how a policymaker considers addressing school shootings through policy.

Several principles of social change have been used as a guide to initiate and sustain change, as well as to navigate some of the challenges that arise in policy work (Jason, 2013). For example, it is important to see the big picture and be careful to identify who the power holders are. Often they like to see things stay the same, particularly if they are gaining resources and privileges in these roles. When identifying power holders, it is useful to understand their motives for continuing to maintain control, and the influence and power that they wield. Certainly, the National Rifle Association has a powerful role in shaping the dialogue on the availability of guns, and their position has contributed to the wide availability of guns throughout the US. To bring about structural and long-term second-order change, rather than just short-term fixes to a problem, it is often useful to work with coalitions and other allies in order to form strategies to confront those who are abusing the power. Often youth who have been traumatized by a school shooting, as well as parents of children who have been killed, have become powerful agents of change, trying to reduce the availability of guns. Being willing to stay committed to an issue over time is critical, as it provides opportunities to get to know the central gatekeepers who might need to be dealt with to bring about second-order change. Ultimately, the situation in the US with school shootings will require patience and persistence, and savoring small wins is crucial to sustaining the motivation to work toward long-term goals.

Other policy interventions have changed the social context as well as other regulatory factors. For example, Gary Slutkin, founder of Cure Violence, deploys credible outreach workers to interrupt conflicts, treat the highest risk individuals, and change community norms. This program has found 34-56% reductions in shootings and killings in sections of Baltimore (Webster et al., 2012), and the program is now being used in countries around the world. When Australia banned rapid-fire guns after a 1996 mass shooting, killings decreased. While there were 13 mass shootings before the gun law reforms from 1979-1996, there were no fatal mass shootings after the gun law reforms from 1997 to 2016 (Chapman et al., 2016). These types of interventions do suggest that violence can be interrupted. More effective solutions will ultimately need to find ways to promote social justice and a sense of community given that educational and economic inequalities have contributed to many of these expressions of violence.

Throughout this policy process, intuition is an essential quality that is relevant, as it often involves a feeling or sense of next steps that need to be taken in strategic coalition-building or political action. Having an intuition that one’s vision will be fulfilled in the long run can be a sustaining and life-affirming force in the face of oppressive conditions. Social policy change leaders will often rely on conjuring up a dream and sustaining it with intuition in order to overcome the obstacles that are faced in community work.

A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

While full participation and involvement are dominant themes within this textbook, the remnants of elitism and non-democratic processes have been present through recorded history, and continue to be widely present today. Anyone can do the following experiment: Think about the setting you spend time in such as your college or school. The Democracy Quiz question is “Who has the power to make decisions?” This deceptively simple question can inform us about whether there is any power-sharing when decisions are made or whether an elite, non-elected group is firmly and totally in charge of decisions. Change at this level will ultimately involve policies that have been reviewed within this chapter and this book.

Today, millions of Americans are locked up or controlled in total institutions whether they are substance abuse treatment settings, nursing homes, mental institutions, prisons or even schools. If one were to administer our Democracy Quiz in such settings, the answers would be telling. In many cases, the participatory spirit of decision-making would be hardly noticeable. For those with fewest resources, for those with the greatest needs, for those with the least opportunities, there is often minimal input on decision-making. In other words, few democratic-type settings are available for those who are discharged from substance abuse treatment facilities, prisons, or mental institutions. These individuals need settings where they can participate as full members, with responsibility and dignity. It is at the policy level that we need to institute many change efforts for those most in need. The broadening self-help moment described throughout this textbook shows us the possibilities when individuals with assorted afflictions are provided decision-making responsibilities and power.

To address many of the difficult policy level problems that we face, it is often important to take a few steps back and consider a historical perspective that accounts for changes that have put our world at risk for its current problems, and provides a way to explore and eventually address these problems on a deeper policy level (Jason, 1997). There was a time when people helped one another, not out of charity, but because it was the natural way of life. But over time there has been a weakening of long-term bonds with the land, family, and community and a reduction of a sense of coherence, and as well as interest, in community participation. Clearly, the computer and artificial intelligence/robotics revolutions have and will increasingly create challenges to larger segments of our population. At the deepest levels, our policy interventions need to ultimately strengthen our relationships and customs which make life more vital, energizing, and comprehensible.

The constant viewing of violence throughout the media and the Internet has led many to feel that there is more violence today. But according to Pinker (2011), evidence from multiple sources indicates that there is actually less violence and homicides over time. But while the percentage of deaths in the total population due to violent conflicts is at a historical low, the actual number of deaths has increased. Clearly, Pinker (2011) has focused his work on rates rather than numbers, and even if rates of physical violence are less, there are other forms of violence that need to be considered including mass incarcerations, inequality, poverty, and racism.

SUMMING UP

We began this foray into the policy arena by considering mounting student debt, an issue that is complicated and ultimately will need to be solved by addressing the many streams that have influenced this unfortunate situation. Often whether it is dealing with student debt, increasing economic inequalities, or school violence, there are historical factors that will need to be understood so we can both understand what has caused these problems and what policies might be considered.

This type of work at the policy level will often need a long-time commitment, and sticking with these types of issues will more likely occur when you are really invested and committed to a social issue. If the problem is not important to you, it is less likely you will continue to fight for change when the inevitable disappointments and feelings of frustration occur. We can look for guidance from those who battled for civil rights, women’s rights and environmental rights, as these struggles occurred over decades. These movements demonstrated that a policy perspective can help overcome even the most significant problems to reach social justice goals.

Critical Thought Questions

- What challenges might arise when trying to get a social issue addressed through public policy?

- A community psychologist has partnered with a local advocacy organization to gain a state-funded mental health center in their community. Using the information on the policymaking process from this chapter, describe how the mental health center may be adopted through policy.

- Reflect on how policies have negatively impacted your community. What are some ways to change these and implement new ones?

- Think back to the small wins of the free online textbook project referenced in case study 14.1. What are some small wins you can think of if you were to try to change or create a policy you care about?

Take the Chapter 14 Quiz

View the Chapter 14 Lecture Slides

_____________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Archbold, Carol. (2012). Policing: a text/reader. (p.5). Sage Publications Inc.

Block, P. (2006). Flawless consulting: A guide to getting your expertise used. Learning Concepts/University Associates. Austin, TX.

Chapman, S., Alpers, P., & Jones, M. (2016). Association between gun law reforms and intentional firearm deaths in Australia, 1979-2013. Journal of the American Medical Association, 316(3), 291-299. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.8752

Clark, K. B., & Clark, M. P. (1947). Racial Identification and Preference in Negro Children. Readings in Social Psychology, 602-611.

Dalton, J., & Wolfe, S. M. (2012). Competencies for community psychology practice. The Community Psychologist, 45(4), 8-14.

Jason, L. A. (1997).Community building: Values for a sustainable future. Praeger.

Jason, L. A. (2013). Principles of social change. Oxford University Press.

Jason, L. A., Beasley, C. R., & Hunter, B.A. (2015). Advocacy and social justice. In V. Chien & S. M. Wolfe (Eds.), Foundations of Community Psychology Practice. (pp. 262-289) Sage.

Jason, L. A., Groh, D. R., Durocher, M., Alvarez, J., Aase, D. M., & Ferrari, J. R. (2008). Counteracting “Not in My Backyard”: The positive effects of greater occupancy within mutual-help recovery homes. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 947-958.

Jason, L. A., Glantsman, O, O’Brien, J. F. & Ramian, K. N (2019). Introduction to the field of Community Psychology. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/intro-to-community-psychology/

Jason, L. A., & Jung, R. (1984). Stimulus control techniques applied to handicapped-designated parking spaces. Deterring unauthorized use by the non-handicapped. Environment and Behavior, 16, 675–686.

Kelly, J. G. (2006). Becoming ecological: An expedition into Community Psychology. Oxford University Press.

Kingdon, J. W. (1995) Agendas, alternatives, and public policies (2nd Ed.). Little, Brown, and Company.

McEvoy, Jemima. (2020, August). At least 13 cities are defunding their police departments.Retrieved November 19, 2020, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jemimamcevoy/2020/08/13/at-least-13-cities-are-defunding-their-police-departments/?sh=4c9508b29e3f

Miller, B. (2017, October 19). New federal data show a student loan crisis for African American borrowers. The Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-postsecondary/news/2017/10/16/440711/new-federal-data-show-student-loan-crisis-african-american-borrowers/

Miller, R. L. (2017). The practice of program evaluation in community psychology: Intersections and opportunities for stimulating social change. In M. A Bond, I. Serrano-García, & C. B. Keys (Eds.), APA Handbook of Community Psychology: Methods for Community Research and Action for Diverse Groups and Issues (Vol. 2). American Psychological Association.

National Academy of Science. (2012). Using science as evidence in public policy. Washington, DC.

Pinker, S. (2011). The better angels of our nature: Why violence has declined. Viking.

Webster, D.W., Whitehill, J.M., Vernick, J.S., & Parker, E.M. (2012). Evaluation of Baltimore’s Safe Streets Program: Effects on attitudes, participants’ experiences, and gun violence. Johns Hopkins Center for the Prevention of Youth Violence, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD. https://web.archive.org/web/20141213023230/http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/web-assets/2012/01/evaluation-of-baltimore-s-safe-streets-program

Wood, M., Turnham, J., & Mills, G. (2008). Housing affordability and family well‐being: Results from the housing voucher evaluation. Housing Policy Debate, 19(2), 367-412.

Acknowledgments: We wish to thank Jamie Archibong for helping to write the section on Public Policy and Structural Inequality.