19

Susan D. McMahon and Bernadette Sánchez

Chapter Nineteen Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand educational degrees at the undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral levels in Community Psychology

- Understand and prepare for career options in the field of Community Psychology

- Consider core research and practice competencies in assessing educational opportunities

- Assess future directions in the field of Community Psychology

- Engage in and contribute to the growth of the field

Now that you have learned about the basics in the field of Community Psychology, how do you want to build upon your understanding of Community Psychology? To what extent would you like to engage in a career that incorporates Community Psychology? What types of educational degrees are available in Community Psychology? What competencies are central in the field of Community Psychology? How do you engage in and contribute to growing the field? What opportunities are there for becoming a social activist? This chapter will address these questions about education, competencies, and engaging in the field in order to provide you with an overview of some next steps.

WHAT EDUCATIONAL PREPARATION DOES A CAREER IN COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY REQUIRE?

There are different types of educational programs available in Community Psychology. We will describe some of the core components of Community Psychology degree programs at the undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral levels, and you can find a list of Community Psychology programs across levels available on the Society for Community Research and Action’s website. Most programs in Community Psychology focus on master’s and doctoral level training. In addition, there are several resources that may be helpful as you explore and consider educational options in Community Psychology (see Glantsman et al., 2015; Jimenez et al., 2016; McMahon et al., 2015; Serrano-García et al., 2016).

Undergraduate Programs

If you are interested in attending a university that has a Community Psychology focus, check out its curricular options in advance because there are few institutions that have a significant focus on Community Psychology at the undergraduate level. For those that have coverage, there is typically a single course. Some universities, though, have developed concentrations or degrees in Community Psychology (Glantsman et al., 2015; McMahon et al., 2010; McMahon et al., 2015). When there is a concentration or a degree in Community Psychology, students will likely gain exposure to multiple content courses, as well as a community-based practicum/fieldwork/internship experience. These experiences may involve working with a non-profit organization that addresses important social issues such as mental health/illness, homelessness, domestic violence, or LGBTQ issues.

Students can receive course credit and group supervision for their hands-on experiences. Even if there is not a Community Psychology concentration at your university, look for Community Psychology relevant internships; students can visit their career center or advisors to find out more. Fieldwork experiences can be tailored to student interests, and students can put the knowledge and skills they have learned into practice. It is often the case that students who engage in these applied experiences with organizations get jobs following the completion of their undergraduate degrees. They are equipped with a range of knowledge and experience related to research, evaluation, systems theory, and intervention.

In addition to internships, another strategy is to reach out to faculty who are engaged in Community Psychology research and interventions. Seek volunteer positions to assist faculty members who are doing community work that you are interested in and passionate about. This will give you invaluable experiences and skills to further your education and training in the field. Develop connections within and outside of your university to be better prepared to take a job in a community-based organization or pursue graduate studies.

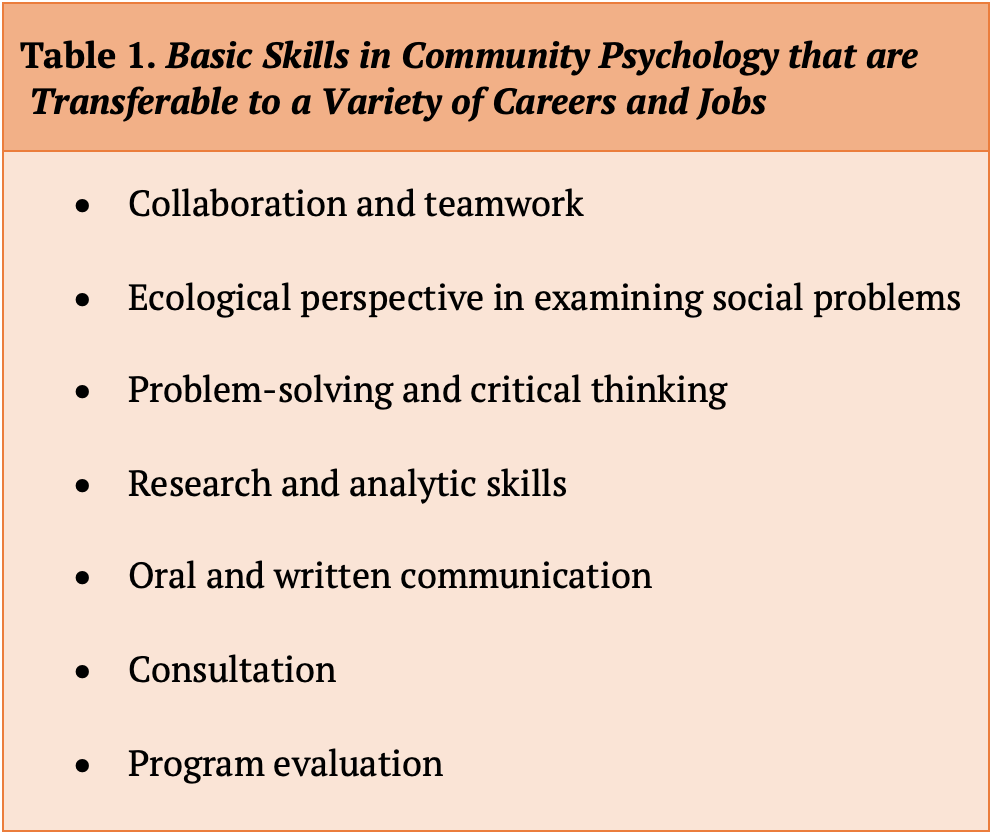

Even if you decide not to pursue Community Psychology for graduate school or work with a community-based organization, an undergraduate course, concentration, or degree in Community Psychology is helpful for a range of career options, including clinical psychology, counseling psychology, social work, law, public health, education, and many other career paths. Basic knowledge and skills in Community Psychology (see Table 1 below) are transferable and helpful in addressing social issues, such as poverty, immigration, violence, substance use, mental health, and criminal justice. In addition to courses in Community Psychology, consider taking relevant business courses to enhance your financial and organizational knowledge, and become technologically, methodologically, and statistically savvy (McMahon & Wolfe, 2016; McMahon et al., 2015; Viola & McMahon, 2010). These skills will be useful, whether you decide to enter graduate school or a career with non-profits, and especially helpful if you are interested in consulting, owning your own business, or the financial aspects of non-profits.

Master’s Programs

Master’s programs in community research and action may have different names, such as Community Psychology, community social psychology, clinical-community psychology, counseling, and interdisciplinary programs in community research and action. Serrano-García et al. (2016) identified 75 graduate programs in Community Psychology around the world. Master’s programs include more intensive theory-practice integration than undergraduate programs and many include intensive practicum experiences. A major difference between master’s and doctoral programs is that master’s programs place less emphasis on research and advanced statistical approaches (Dziadkowiec & Jimenez, 2009) and more emphasis on practice than doctoral programs (McMahon et al., 2015).

In many countries, master’s programs are the most typical type of post-graduate program. Most students who enroll in master’s programs are preparing for practice careers in Community Psychology. The timeline to complete a master’s degree is about 2-3 years versus 4-6 years in a doctoral program. Master’s students, in general, are less likely than doctoral students to enroll full time, and many part-time students are employed full-time in local community organizations (McMahon et al., 2015). Thus, there are rich opportunities for students to apply the new knowledge and skills they gain in Community Psychology master’s programs to their organizational and community work.

Doctoral Programs

Doctoral programs in Community Psychology tend to include advanced theory, practice, and comprehensive research competencies, and they prepare students for many career options. There are about 45 self-identified community research and action doctoral programs that are community, clinical-community, or interdisciplinary programs. Many of these doctoral programs are in the US and have a primary focus on research, but programs worldwide vary in the extent to which various competencies are emphasized. In the US, some programs train students in clinical-community psychology while others are focused solely on Community Psychology. The difference between clinical-community and Community Psychology is that students in clinical-community programs receive training in both clinical (e.g., courses in psychopathology, therapeutic approaches, and clinical areas) and Community Psychology, while students in Community Psychology do not receive clinical training but may receive an interdisciplinary education with Community Psychology as the central focus.

The tradition of doctoral education has historically emphasized the discovery and production of new knowledge through field-specific, and often mentor-based, research opportunities (Austin & McDaniels, 2006). Although traditional doctoral programs may primarily prepare students to become researchers and academicians, doctoral programs are also providing training in the Community Psychology practice competencies (Sánchez et al., 2017) such as evaluation, consulting, and grant-writing. This skill set enables students to go onto a variety of career paths, including community-based organizations, healthcare, education, public policy, government, foundations, and business [see Kelly and Viola’s (2019) Chapter 3 in this book for careers in Community Psychology].

International Programs

There are over 35 master’s programs throughout the world, including those in Argentina, Australia, Canada, Chile, El Salvador, Egypt, Greece, Italy, New Zealand, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, United Kingdom, and the US. Doctoral programs also span a variety of countries, including Australia, Canada, Italy, New Zealand, Puerto Rico, and the US (Serrano-García et al., 2016). Outside of the US, educational programs cater to niches based on the country’s culture, history, and career opportunities. For example, a master’s program in Community Psychology at Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (PUCP) prepares students for careers in the government, and graduates enter positions in which they develop and evaluate programs for Peruvian people within various governmental branches (T. Velázquez Castro, personal communication, June 12, 2013). The master’s program in Community Psychology at the American University in Cairo, Egypt focuses on preparing students to work as consultants or in non-governmental organizations (NGOs) where they primarily engage in capacity building activities and community development (M. Amer, personal communication, October 25, 2013). In Latin America, some programs have an emphasis on community social psychology; many graduates work with community organizations, healthcare, education, and to a lesser extent, clinical practice (N. Portillo, personal communication, October 25, 2013). Educational programs are nested within their cultural context, so if you are interested in working with a particular population, you may choose to seek training in that region of the world.

Practical Application 19.1

Who Should Write my Letters of Recommendation for Ph.D. Program Applications?

We recommend that you ask at least one faculty member with who you have engaged in research. If you have two to three significant research experiences, all of your letters could be from research mentors. If you only have one notable research experience, then your other letters should be from a mentor or supervisor from an internship or volunteer experience, and from an advisor, instructor, or mentor with whom you have a strong relationship. The strongest letters will come from people who know you well, have worked with you for at least six months, and can speak to a range of your abilities, your fit with the program, your career goals, your research and academic skills, your motivation, work ethic, character, etc. Letters from instructors who simply taught courses that you took tend not to provide the edge that you need to get into competitive doctoral programs. Finally, when you ask individuals for a letter of recommendation, ask them, “Can you write a strong letter of recommendation for me?” If they hesitate and can’t give you a definitive “Yes,” then you don’t want them to write you a letter of recommendation.

Applying to Graduate Programs

If you believe that graduate study in Community Psychology is an excellent fit with your career goals, there are several strategies that may be helpful including 1) ensuring you have significant research experience, and if you don’t, volunteering to join a research team doing work you find interesting; 2) preparing to take the Graduate Record Exam (GRE), and considering a formal course, tutoring, or re-taking the test if your scores are weak; 3) building relationships with faculty and people working in the field, as you generally need three strong letters of recommendation (see Practical Application 19.1 above); 4) exploring and applying to a range of programs including both master’s and doctoral programs, and making sure the program is a good fit with your interests and career goals; 5) if you are invited for a visit, try and attend one – it will be beneficial for faculty to learn more about you, and you will get a good sense of which programs will be the best fit for you; 6) talking with current students to get a sense of the program from a student perspective; 7) assessing the balance of theory, research, and practice, as well as the core competencies that are taught in the program; and 8) learning about the various career paths of graduates of the program. People who are engaged in the field of Community Psychology tend to be passionate about the values of the field and the mission toward social justice and action, so getting advanced training is an excellent way to become better equipped to make a difference in the world and follow your passion.

COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY PRACTICE COMPETENCIES

As you consider what educational level you want to achieve and the programs that are a good fit with your interests and career goals, it is important to consider the competencies that you hope to achieve through your undergraduate and/or graduate education. Although there is overlap across programs, different programs emphasize certain competencies more than others. Some are focused more on theory and others are more focused on practice. Thus, you will want to examine exactly what certain programs are training students to do. Below we summarize an array of competencies that have been identified in the field, specifically related to practice and research.

Practice Competencies

The Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA), the official organization of Community Psychology, has identified 18 core practice competencies (described in Chapter 7 by Wolfe, 2019) related to five themes that are commonly used in Community Psychology careers: 1) foundational principles (ecological perspectives; empowerment; sociocultural and cross-cultural competence; community inclusion and partnership; ethical and reflective practice), 2) community program development and management (program development, implementation, and management; prevention and health promotion), 3) community organization and capacity building (community leadership and mentoring; small and large group processes; resource development; consultation and organizational development, 4) community social change (collaboration and coalition development; community development; community organizing and community advocacy; public policy analysis, development and advocacy; community education, information dissemination, and building public awareness) and 5) community research (participatory community research; program evaluation; Dalton & Wolfe, 2012). Most careers will tap into multiple competencies, while some will emphasize and require advanced skills in particular areas.

Research Competencies

SCRA has also identified research competencies that are important for community psychologists. Similar to the practice competencies, it is not expected that community psychologists gain mastery in all of these research competencies but will gain at least exposure to them and experience with some. There are five foundational competencies that underlie all areas of research, including a) research questions and leverage points, b) participatory community research, c) managing collaborations, d) developing community change models, and e) program evaluation (Haber et al., 2017). Further, there are specific research competencies in the areas of research design (e.g., survey design, sampling, mixed methods), data analysis (e.g., descriptive quantitative analyses, basic qualitative methods, missing data and data reduction techniques), and theories and perspectives (e.g., ecological theories, empowerment, policy change; Haber et al., 2017).

In their review of graduate program competencies, as well as the SCRA practice competencies listed above, Serrano-García and colleagues (2016) suggest that these competencies fall into four general categories: knowledge (e.g., application, articulation, integration), research (e.g., methodology, data analysis, writing proposals and reports), cognition, (e.g., identify, analyze, understand, and communicate injustice, values, social context) and practice/profession (e.g., develop, implement, and evaluate interventions, promote social change, demonstrate multicultural competence). Here are some questions to reflect on as you consider educational programs, review the curricula, consider your interests and desired skills, and focus on developing the competencies that will be most relevant for your desired career path. Which competencies are you most interested in learning about? Which competencies do you envision using in your desired career? Which graduate programs will help you develop your desired competencies?

SOCIAL ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE

Many individuals pursue the field of Community Psychology because of their interests in social change, and perhaps you are one of these individuals. There are a variety of ways in which you may become an activist to influence the assessment, interventions, or policies that relate to a particular population or social issue. While the field of psychology has traditionally focused on understanding individual behavior and problems as well as treating them at the individual level, Community Psychology is focused on the interaction between the individual and the environment and understanding individual problems from an ecological perspective (see Chapter 1 by Jason et al., 2019). Because of the values of our field (e.g., diversity, social justice), community psychologists are also interested in changing community and societal issues to ultimately better the lives of individuals. Some community psychologists have dedicated their lives to being scholars and activists in order to create social change. For example, Balcazar and Suarez-Balcazar (2016) have developed and tested community-based interventions that target individual behaviors (e.g., skills, awareness, knowledge) as well as factors in the environment (e.g., accessibility, resources, policies) that affect the lives of people with disabilities. They have also used the Concerns Report Method to help identify community members’ concerns, which are then used to take action on their concerns (see Case Study 19.1 for a description of the Concerns Report Method and how it has been used in various communities around the world).

Case Study 19.1

The Concerns Report Method

While a graduate student at the University of Kansas, community psychologist Yolanda Suarez-Balcazar participated in the development of a community-based participatory methodology, informed by Community Psychology Ecological Systems Theory as well as Applied Behavior Analysis, to identify community concerns and take action. The methodology, called the Concerns Report Method, includes mixed methods, such as focus groups in which community concerns are identified by groups of individuals, development of a concerns survey, survey administration and data analysis, followed by town hall meetings to discuss results and plan actions to address identified issues of concern. Early applications of the Concerns Report Method included addressing the concerns of people with disabilities, such as handicap parking violations. Both Yolanda and Fabricio Balcazar have applied this participatory intervention methodology in collaboration with diverse community contexts. These Include collaboration with residents of Golfito, Costa Rica, who were experiencing displacement by a large multinational corporation; immigrant Latino families living in a suburb of Chicago to identify and address health concerns; Colombian immigrants in the city of Chicago. Most recently Fabricio and a group of community partners applied the Concerns Report Method in Juanaclatan, Mexico. As a result of the implementation of the Concerns Report Method in Mexico, the community addressed several issues such as getting the Governor to allocate funds to treat the contamination of a local river, providing new services for families affected by domestic violence with funds from immigrants living in Chicago, establishing a new community center built by community volunteers on land donated by the local church, and developing new recreational programming for youth. For applications of the Concerns Report Method, check the following resources in the references (Balcazar et al., 2009; Suarez-Balcazar et al., 2005; Suarez-Balcazar & Balcazar, 2016).

Another approach to creating social change is by influencing social policy, and there are several ways that you may go about affecting it. Policy work is important because it is an avenue for psychologists to apply psychological principles to benefit public interest. Community psychologists are well positioned to conduct policy-relevant research and influence social policy to improve the quality of life for many people. Maton (2017) interviewed 79 psychologists (mostly developmental, social and/or community psychologists) about their careers as influencers of social policy. These interviews revealed that there are four key skills that participants used to change social policy, including a) building relationships with policymakers, staff members at intermediary organizations, media, practitioner groups, and/or researchers, b) research skills to conduct original research, evaluate research evidence, and to synthesize research literature, c) oral and written communication skills, and d) strategic analysis skills. Further, there were a variety of ways that these psychologists influenced social policy, such as serving as a member or chair of a policy advisory group, advocacy and lobbying, educating the public through the media, and sharing relevant psychological research and theory in key court cases. A key lesson that community psychologists share is the importance of being patient and persistent, as creating social change takes a long time and one may face many barriers and failures along the way. Jason (2013) advises community psychologists to take small steps to influence social change; small steps may include creating and signing petitions, attending a protest, contacting local legislators, and writing a policy brief.

There is much work to be done by community psychologists in both research and practice that is relevant to social action and social change. Systems can support or even promote violence and oppression. Langhout (2016) mentions several examples of state-sanctioned violence in the US, as well as movements that emerged in response to this violence in Fuerguson, Charleston, and other locations in the US. The violent act occurs in society on the ecological level, and the society responds by organizing and creating a movement in defense of those unjustly harmed.

Langhout (2016) argued that community psychologists need to use liberatory approaches and practices in order to transform society and truly free oppressed peoples. She calls on community psychologists to build on the work of feminist scientists, critical feminist social psychologists, and critical feminist social-community psychologists who focus on “the study of subjectivity, process, change, connectivity, desire, and difference” in order to build solidarity with the people most affected by state-sanctioned violence and disrupt the structures (e.g., whiteness, patriarchy, class privilege) that support the violence (p. 325).

AREAS FOR FUTURE DEVELOPMENT

Several textbooks including the current one by Jason et al. (2019) have identified areas of future work for community psychologists, which are summarized below. These are topics that any student in Community Psychology can pursue in their career and/or educational path.

Appreciation for Differences and the Search for Compassion

Given increasing globalization and migration in various societies around the world, an appreciation for different types of diversity based on background, experiences, or cultures is important in helping individuals and communities with problem-solving, innovation, creativity and informed decision making. In addition to an appreciation for diversity, compassionate attitudes are essential in order to effectively help others who are suffering. Our field could benefit from research investigating appreciation of diversity and compassion as outcomes rather than only as predictors. For example, researchers can examine the structural qualities that predict appreciation of differences and develop interventions that create compassionate communities (Moritsugu et al., 2014).

Sustainability and Environmental Concerns

Climate change and waste of natural resources have been pressing issues around the world. Many view climate change as a human rights and social justice issue, as it disproportionately impacts poor communities around the globe (Levy & Patz, 2015). For example, the environmental consequences of climate change influences access to safe food and water, which negatively affects health. Foodborne and waterborne diseases, respiratory disorders, and malnutrition are a few of the consequences (Levy & Patz, 2015). Given our field’s values towards helping oppressed communities, addressing climate change along with environmental classism and racism would prevent further health and economic problems in communities.

Disparities in Opportunity for Health, Education, and Economic Success

In the United States, the gap between the rich and poor is at an all-time high. Specifically, the median wealth of upper-income families was seven times greater than middle-income families and 75 times greater than lower-income families in 2016; for comparison purposes, the median wealth of upper-income families was 28 times the wealth of lower-income families in 1983 (Pew Research Center) (Kochhar & Cilluffo, 2017). There are also racial differences in wealth, with Latinx and African-American families having disproportionately less wealth than White families (Kocchar & Cilluffo, 2017). These economic and racial inequalities influence access to quality schooling, health care, and job opportunities. In Chapter 1, Jason et al. (2019) indicated that policy changes and increased political involvement are necessary to reduce these disparities. Further, they suggest that community psychologists examine ways to remove structural obstacles in order to reduce disparities.

Aging and End of Life

Issues of aging are generally understudied in psychology, and Moritsugu et al. (2014) encourage community psychologists to research and create interventions to help with enhancing the quality of life for our growing elderly population around the globe. Further, our society values life and vitality, and hence, discussions of death and dying are taboo. Community psychologists could do much to help individuals and their families and communities better deal with and face death and dying head on and support loved ones as they grieve. There are countless important global issues to address and populations to work with to make a difference – the choice is yours and will depend on where your passion lies.

NEXT STEPS TO CONSIDER IN YOUR COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY CAREER

Engaging in the Field

Engaging in the field is an important next step and can give you energy, social connections, and resources that will facilitate pursuing your passion. There are many opportunities to connect with people who have similar values and are interested in applying these values to their work. Join SCRA and the SCRA listserve, and get involved in leadership opportunities. SCRA27 provides helpful information for members, including opportunities to get involved in interest groups, committees, councils, and the Executive Committee. In addition, the website includes lists of undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral programs in Community Psychology, teaching materials, policy statements, webinars and blogs, and other helpful resources. Build your networks within and across your discipline and collaborate with others (McMahon et al., 2015; McMahon et al., 2016). Engage in professional development to stay current and grow your knowledge and skills through conferences, webinars, and workshops. Continuing education opportunities provide an avenue to grow stronger networks of community psychologists sharing their work and promoting community change across generations and settings (Jimenez et al., 2016). For example, the regional student-run Eco-Community Psychology Conferences (Flores et al., 2013) are a great place to network with other students, and these conferences have been occurring for the past 40 years. Another way to learn more about specific skills of interest is to explore and become familiar with the Community Tool Box. This online resource has a plethora of helpful guides to facilitate social action, including assessing community needs and resources, developing a model of change, developing strategic and action plans, developing an intervention, evaluating the initiative, and applying for grants.

Use the field to guide your work. Research is an important component of Community Psychology, so check out the literature on topics of interest, read the current research, and explore what others have done before you start something new. There are many empirically-based programs, so don’t re-invent the wheel without first learning what others have spent years creating and testing. Assess the extent to which existing theories, strategies, and programs have been applied to work in your area. Using specialized resources in your university libraries (if you have access) such as APA PsycInfo® and Social Sciences Abstracts, as well as free online tools like Google Scholar, ResearchGate, and PubMed®, can guide your work. If you can’t access articles you need that are relevant to your work, try requesting them from the authors via email.

Follow your passion to make a difference. Appreciate “small wins” and engage in self-care. Working systemically to promote health and well-being among underserved populations is important work that can have far-reaching effects at the local, regional, state, national, and international levels. Be patient, and don’t try to do it all at once; figure out where your talents lie and where you can make a difference and work with others to have a larger impact.

Growing the Field

Our field is small but of utmost importance – can you think of anything better than to work toward solving the world’s problems through strategic, systemic, evidence-based practices in collaboration with organizations, communities, and government? You can help grow the field through a variety of strategies, such as 1) connecting with your local and national organizations to increase awareness of Community Psychology competencies and the fit with their work; 2) using technology and social media to increase visibility of good work in the field, such as through Twitter, blogs, Linked In, Instagram, Facebook, and videos that illustrate exemplary projects and public discourse on social issues; 3) looking for opportunities to introduce yourself as a community psychologist or someone who has training in Community Psychology. You should have an “elevator speech,” in which you provide brief bullet points about the field and what we do. Community psychologists add distinctive value through the ways in which we combine science, understanding of systems, and an ecological approach to contribute to an adaptive, collaborative team approach to sustainable change (Community Psychology Practice Council, 2010). You need to be able to describe to others what you bring to the table quickly and in user-friendly ways.

Disseminate your work through various outlets to yield greater visibility and impact for our field (Jimenez et al., 2016). Be politically and socially active in your community and share your work with communities across levels (e.g., locally, regionally, nationally). In addition to traditional academic outlets, submit articles and Op-Eds about your work to local newspapers, newsletters, websites, blogs, and other sources to let the public know about your Community Psychology-related work and impact (McMahon & Wolfe, 2016). Disseminating your work through social media helps keep the work current, relevant, and linked with those who find it most helpful (Jimenez et al., 2016). Communitypsychology.com is a website that SCRA created to interact with the public and share the important work we are doing; consider submitting your research or practice work – there is an array of topics, including education, health care, children, environmental issues, prevention, criminal justice, public policy, substance use, violence, and housing. The field of Community Psychology offers a wealth of knowledge, skills, strategies, research methodologies, and interventions to create a more socially just society – now it is up to us to grow the field using a multi-pronged approach to action and dissemination.

Here are some questions to consider as you reflect on the next steps in your potential future career in Community Psychology. What are the issues that you care about most? How can you as an individual get involved in addressing these issues? What would you do differently based on the material you learned about in this book? How can you join with others, such as through local, regional, national, or international organizations, to make a difference? We have created an “Action Checklist” below to help you answer these questions.

Practical Application 19.2

Action Checklist

Below is a list of ways you can get more involved in Community Psychology.

- Take political action

- Organize or participate in a rally

- Contact your local, state, and/or national legislators on important issues

- Start or sign a petition to share voices of concerned citizens

- Volunteer in your community

- Offer skills you have to promote a cause that you care about.

- Use social media effectively to raise awareness

- Transition from personal to professional usage

- Write blogs and/or Op-Eds to share your perspective to a wide audience

- Find a job that provides a forum for social action on issues you are passionate about

- Use and share the Community Toolbox as a resource to guide social action

SUMMING UP

After learning about the field of Community Psychology, consider which path will facilitate your journey and what your next steps might be. There are undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral level courses and programs around the world that can be beneficial depending on your experience and career goals. Consider social issues that matter to you and the Community Psychology competencies that will help you address these issues as you plan for your career. Gaining research skills and applied experiences through Community Psychology education will provide you with tools to effect social change. Join and become meaningfully involved in SCRA to connect with the field and a community of scholars and practitioners with similar values. Learn about others’ work, share resources and knowledge, and collaborate with colleagues to become the next generation of transformative community psychologists.

Critical Thought Questions

Consider the following questions to assess whether you may be best equipped for an undergraduate, master’s, doctoral, and/or international education.

1. What would you like to do when you finish your education? How might Community Psychology be part of your career plans?

2. What skills would you like to use in your work?

3. With what populations and in what settings would you enjoy working?

4. Have you been involved with research? If so, do you like it? Many people think they don’t like research, but once they try it, they find it to be very interesting.

5. How much do you see research or evaluation as part of your job description? How might you apply research or evaluation in a setting to assess and modify work being done?

6. How much do you see program development and management as part of your role?

Take the Chapter 19 Quiz

View the Chapter 19 Lecture Slides

_____________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Austin, A., & McDaniels, M. (2006). Using doctoral education to prepare faculty to work within Boyer’s four domains of scholarship. New Directions for Institutional Research, (129), 51-65.

Balcazar, F., Garcia-Iriarte, E., Suarez-Balcazar, Y. (2009). Participatory action research with Colombian immigrants. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 31(1), 112-127.

Balcazar, F. E., & Suarez-Balcazar, Y. (2016). On becoming scholars and activists for disability rights. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58, 251-258.

Community Psychology Practice Council (2010). An evidence-informed Community Psychology value proposition. http://www.scra27.org/files/4513/9007/7333/Evidence_based_CP_Value_Proposition__Final_20110829.pdf

Dalton, J., & Wolfe, S. M. (Eds.). (2012). Education connection and the community practitioner. The Community Psychologist, 45(4), 7-13.

Dziadkowiec, O., & Jimenez, T. (2009). Educating community psychologists for community practice: A survey of graduate training programs. The Community Psychologist, 42(4), 10-17.

Flores, S., Jason, L. A., Adeoye, S. B., Evans, M., Brown, A., & Belyaev-Glantsman, O. (2013). The evolution and growth of the Eco-Community Psychology conferences. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 4(2), 1-8. http://www.gjcpp.org/pdfs/2012-006-final-20130502.pdf

Glantsman, O., McMahon, S. D., & Njoku, M. G. C. (2015). Developing an undergraduate Community Psychology curriculum: A case example. In M. G. C. Njoku, C. C. Anieke, & P. J. McDevitt (Eds.), Frontiers in education: Advances, issues, and new perspectives. ABIC Books.

Haber, M. G., Neal, Z., Christens, B., Faust, V., Jackson, L., Wood, L. K., Scott, T. B., & Legler, R. (2017). The 2016 survey of graduate programs in Community Psychology: Findings on competencies in research and practice and challenges of training programs. The Community Psychologist, 50(2), 12-20.

Jason, L. A. (2013). Principles of social change. Oxford University Press.

Jason, L. A., Glantsman, O., O’Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. (2019). Introduction to the field of Community Psychology. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an Agent of Change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/intro-to-community-psychology/

Jimenez, T. R., Sánchez, B., McMahon, S.D., & Viola, J. (2016). A vision for the future of Community Psychology education & training. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58, 339-347.

Kelly, A., & Viola, J. (2019). Who we are. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/who-we-are/

Kochhar, R., & Cilluffo, A. (2017, November 01). How U.S. wealth inequality has changed since the Great Recession. Pew Research Lab. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/11/01/how-wealth-inequality-has-changed-in-the-u-s-since-the-great-recession-by-race-ethnicity-and-income/

Langhout, R. D. (2016). This is not a history lesson; this is agitation: A call for methodology of diffraction in US-based Community Psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58, 322-328.

Levy, B. S., & Patz, J. A. (2015). Climate change, human rights and social justice. Annals of Global Health, 81(3), 310-322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2015.08.008

Maton, K. I. (2017). Influencing social policy: Applied psychology serving the public interest. Oxford University Press.

McMahon, S. D., & Wolfe, S. M. (2016). Career opportunities for community psychologists. In M. Bond, I. Serrano-García, & C. B. Keys (Eds.), Handbook of Community Psychology: Volume II. (pp. 645-659). American Psychological Association.

McMahon, S. D., Jason, L. A., & Ferrari, J. R., (2010). Community psychology at DePaul University: Emphasizing urban education in America. In C. Vázquez, D. Pérez Jiménez, M. F. Rodríguez, & W. P. Bou (Eds.), International Community Psychology: Shared Agendas in Diversity. (pp. 419-449). Actividades d Formación Comunitaria, Inc.

McMahon, S. D., Jimenez, T. R., Bond, M. A., Wolfe, S. M., & Ratcliffe, A. W. (2015). Community Psychology education and practice careers in the 21st century. In V. C. Scott & S. M. Wolfe (Eds.). Community Psychology: Foundations for Practice, (pp. 379-409). Sage Publishing, Inc.

Moritsugu, J., Duffy, K., Vera, E., & Wong, F. (2014). Community Psychology (5th ed). Routledge.

Sánchez, B., Jimenez, T., Viola, J., Kent, J., & Legler, R. (2017). The use of Community Psychology competencies in a fieldwork practicum sequence: A tale of two graduate programs. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 8(1), 1-24.

Serrano-García, I., Pérez-Jiméne, D., & Rodrigues Medina, S. (2016). Education & training in Community Psychology. In M. Bond, I. Serrano-García, & C. B. Keys (Eds.), APA handbook of Community Psychology: Methods for community research and action for diverse groups and issues (Vol. 2, pp. 625-644). American Psychological Association.

Suarez-Balcazar, Y., Matinez, L., & Casas-Byots, C. (2005). A participatory action research approach for identifying the health service needs of Hispanic immigrants. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 19, 145-163.

Suarez-Balcazar, Y., & Balcazar, F. (2016). Functional analysis of community concerns: A participatory action approach. In L. A. Jason & D. Glenwick (Eds.), Handbook of Methodological Approaches to Community-based Research. (pp. 315-323). Oxford University Press.

Viola, J. J. & McMahon, S. D. (2010). Consulting and evaluation with nonprofit and community-based organizations. Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Wolfe, S. M. (2019). Community Psychology practice competencies. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/practice-competencies/

Acknowledgments: We are very grateful to the following graduate students who contributed to the photographs, glossary, and quiz: Kayleigh Zinter, Wendy de los Reyes Moore, and Kailyn Bare.

Thoughtful combining of qualitative and quantitative data collection methods.

A focus on the individual where the influence of larger environmental or societal factors is ignored.