4

Ronald Harvey and Hana Masud

Chapter Four Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand why it is important to adopt an international perspective on Community Psychology

- Recognize how an international context differs from at-home Community Psychology

- Appreciate the challenges and rewards of doing International Community Psychology work

“The farther one travels, the less one knows.”

– George Harrison, “The Inner Light”

In this book, you will learn about the different theories of Community Psychology and how community psychologists work and interact with people in their communities, as well as with local and national governments and policymakers to promote social change. Now, think about doing Community Psychology work in a country you know little about. This is called International Community Psychology, and it occurs when community psychologists from one country work or train in a country other than their own. The opening Harrison quote, inspired by the 2500-year-old text the Tao Te Ching, implies that exposure to diverse environments and context helps us realize how much more we need to learn. Although humbling, this is the value of adopting an international perspective in Community Psychology.

In this chapter, we will describe some of the similarities and differences International Community Psychology has with “domestic” Community Psychology, and give examples of some of the unique challenges and rewards of doing International Community Psychology work.

WHY STUDY INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY?

Why might you be interested in International Community Psychology? First, we believe international work can sharpen your Community Psychology skills because international research and practice can intensify values and goals, in contrast to doing work in more familiar in-country environments. Experienced International Community Psychology practitioners often report that their international work creates opportunities for reflection and self-discovery, and helps them to better understand context (Harvey & Mihaylov, 2017). We will explore this in more detail later in the chapter.

Second, because of globalization, the world is becoming more interconnected via communications technology, travel, immigration, and trade. While trade is occurring in money, goods, and services, trade is also occurring in symbols, morality, cultural values, governmental systems, and most importantly, people. We live in an ever-increasingly global community where we must consider the global context to address the root causes of local social problems. Community Psychology practices must be informed by global perspectives to understand the contexts in which people live.

TYPES OF INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY WORK

International Community Psychology practice occurs when Community Psychology practitioners from one country work in a different country or culture. This may occur because the practitioners are invited to do research by native residents, or because the practitioners themselves have initiated this contact.

Invitations to do International Community Psychology happen for many reasons: the community psychologist may have expertise in an intervention or field which the host country lacks, or is invited to teach Community Psychology methods to students and practitioners. The following case study from Harvey and Mihaylov (2017) illustrates such an invitation given to Douglas D. Perkins, a community psychologist at Vanderbilt University in the US.

Case Study 4.1

Douglas D. Perkins Engaging in International Work In 1998

“[…] I was invited as a visiting professor in Perth, Australia. The trip involved giving Community Psychology and community development research and academic program development talks and consultations all over Australia (and I also spent time in New Zealand). But I did not really consider myself an international researcher until 2003, when as director of the program in Community Research & Action at Vanderbilt, I was invited to deliver a keynote address at the National Congress on “Prevention in Schools and Communities: Development of Social Capital for Health Promotion and Prevention” at the University of Padova, Italy, and to teach a 2004 graduate master class at Otto-von-Guericke University in Magdeburg, Germany. These opportunities produced my first international research collaborations. I subsequently developed other collaborative research and educational projects with other faculty and students in Italy, China, and South Africa, and many of those faculty and students have also been visiting scholars in our program at Vanderbilt.”

In contrast, initiating International Community Psychology may occur because a home practitioner desires to learn something new or useful that can only be obtained by doing the research or intervention in an international setting. For example, Vassileva et. al (2007) explored the changes in impulsivity in former heroin users over time. However, they faced the issue that the vast majority of people with substance use disorders in the US abused more than one substance before seeking treatment. This methodological challenge was overcome by recruiting participants in Bulgaria, who, because of societal and economic factors, tended to only use heroin.

A third model of International Community Psychology, but one that we would not recommend, is research or intervention forced upon the local or indigenous culture. This sometimes occurs when large funders (e.g., the World Health Organization) attach conditions to the funds being spent. For example, Burchett et al. (2012) interviewed Ghanan psychologists who had a negative view of international health policy from foreign funders that delegitimized traditional birth attendants for home births. The funders forced an intervention using only nontraditional birth workers but provided no funding for training additional birth workers to make up the deficit. This is something that we do not advocate because it is a form of colonialism and violates many Community Psychology values. Colonialism is the act of an invading culture establishing political and economic control over an indigenous people. We need to do all that is possible to not support Colonialism when working internationally.

The last example is of Community Psychology training occurring in another country. See the case study below for an example describing Nikolay L. Mihaylov, at the Medical University of Varna, Bulgaria.

Case Study 4.2

Nikolay L. Mihaylov Meets Community Psychology

“In 2009 I was applying to study psychology in the US with the long-term goal of working on social issues in my home country Bulgaria. Community Psychology was not the instrument I sought: it was absent in textbooks or lectures available in Bulgaria (some of them popular US intros to psychology). Based on an Elliot Aronson-inspired view of social psychology, I applied to a dozen such programs only to discover, to my dismay, that none would admit me, despite my eloquent action-focused personal statement and despite the boost of a Fulbright grant. Then fortune and the Fulbright Commission put me in touch with Ron Harvey, at the time a Ph.D. student at DePaul University. And so I met Community Psychology.

Community Psychology captivated me with its inherent direct work with and in communities, with people. I found that to be the essence of psychology, what drew me to it in the first place—human contact and a spontaneous need to share human presence. In this regard, I felt there was too little training and emphasis on interpersonal skills, consultation, leadership, group dynamics and community organizing in the Community Psychology programs I was first introduced to.

The last impression I would like to share is of my initial awe of how rigorous and busy research in Community Psychology was. Compared to European and Eastern European academic styles, the tempo and rigor in the US is mind-blowing. This makes US academia much more productive and relevant. On the downside, businesslike benchmarks for good work seem to prioritize efficiency over reflection in the process of research. In Community Psychology, such a tradeoff might be bad for community.”

INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY AS A METHOD TO UNDERSTAND CONTEXT AND CULTURE

International Community Psychology is not different in kind from domestic Community Psychology, but it does differ in scope, logistics, open-mindedness, power dynamics, expressiveness, and sensitivity (SLOPES). The most obvious differences when working in another country is its culture. Broadly, culture is the “way things are done around here” (Shweder, 1990). Culture includes everything from the foods we eat and like (and dislike) to language, customs, symbols, artifacts, history, roles, beliefs, and arts. Culture is a large part of the ecological model in which individuals live.

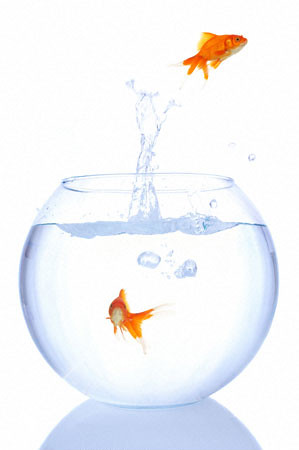

Culture is everywhere; nations, towns, and even your university has its own unique culture. We are often unaware of the impact of our own culture on our thinking. David Foster Wallace related the story in a 2005 commencement speech to Kenyon College graduates, which we roughly paraphrase: if you asked a fish what it is like to be a fish, the fish would probably tell you lots of things except that they are wet—all the time. We may not comprehend this impact until we travel to another place and experience the disorientation of the “way things are done around here.”

This disorientation is called culture shock. Community psychologists working internationally will most likely experience culture shock, but analyzing this disorientation can be one of the great values of doing International Community Psychology work. Although all Community Psychology practitioners have interdisciplinary training and strive for cross-cultural competence, experiencing culture shock when doing International Community Psychology work exposes hidden contexts and encourages self-examination.

For example, when working on creating recovery homes in Bulgaria, Ronald Harvey, who is from the US, learned of a group of recovering individuals in Bulgaria who self-organized and lived together in a communal apartment in Sofia, the capitol city. Through his Bulgarian collaborators, a meeting was arranged so the guest researcher could learn about how these Bulgarian grassroots efforts are similar to and different from the Oxford House recovery home system that was developed in the US (watch Ron Harvey talk about the Oxford House model). This is also an opportunity for a guest community psychologist to understand the Bulgarian context for recovery. This grassroots model of self-help recovery that is emerging in Bulgaria could have enormous implications for those needing these services in Bulgaria and other countries in Europe. Conversations such as these help the international researchers to learn things that may help others, and to ask questions to determine what, how, and why systems or beliefs exist in that society. Experiences such as these can make one recognize the privileges one takes for granted in their home country.

Community Psychology is concerned with societal and systemic themes of prevention, social justice, and an ecological understanding of people within their environments, as indicated in Chapter 1 (Jason et al., 2019). Indeed, the concepts of prevention, social justice, and even “community” are likely to vary in the culture one is working in. Therefore, the main challenge of research and practice of International Community Psychology is to work through the discomforts and disorientation. This is reflected in the proverb, “A bad day for the ego is a good day for the soul.”

Another valuable experience gained in international settings is to expose ethnocentrism—using one’s own culture as the normative standard to judge another culture. When working in another country, one is a guest and to prejudge a different culture limits our understanding of context. Community Psychology takes a systems perspective, meaning that the international community psychologist is required to more deeply examine context to understand why things are the way they are. This tends to quiet the ethnocentric voice and opens the International Community Psychology practitioner to new possibilities for solving social problems. Because international settings likely have a radically different history and culture from one’s own, it is important to understand some of these historical forces that shape culture. The next section explores some of these forces.

INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY AS A METHOD TO UNDERSTAND HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Community psychologists understand that existing power structures and institutionalized injustice can make it difficult to bring about change (Fetterman & Wandersman, 2007; Zippay, 1995). Therefore, transforming communities, changing lives, and promoting equity and social justice through action will often require us to gain an understanding of how power manifests itself within a global context. Imperialism, capitalism, and colonialism are often existing where the power is located, and we need to do all we can to think about how these affect the people we are working with. The development of Community Psychology in the Americas, Asia-Pacific, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa was different in origins, histories, and applications based on these regions’ sociopolitical context. In Latin America and South Africa, the history of the field is based on liberation and social justice (Reich et al., 2007). Understanding the historical context allows us to highlight current issues. For example, Palestinian mental healthcare, existing under an occupation and apartheid system, reveals the complex intersections of mental health, human rights, and social justice, which apply to diverse racialized and indigenous groups locally and globally.

Let’s look at the following case study when considering the effect policy has on society. One of the most debilitating illnesses is called Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, and those who have it have more limitations than in just about any other chronic condition. Yet, in the mid-1980s, the Centers for Disease Control in the US changed the name to “chronic fatigue syndrome” (CFS), and soon after, public officials and scientists throughout the world were using this term. The name is stigmatizing and extremely disliked by patients throughout the world because the term trivializes the illness; everyone feels fatigued at some point so it does not sound like a serious illness. It would be like calling an illness “chronic cough syndrome” when the person really had bronchitis or emphysema. The case study below illustrates what can occur to deal with this problem and the global negative consequences of these unfortunate naming policies enacted in the US.

Case Study 4.3

The Importance of a Name

Patient advocates with the above-mentioned illness have wanted a more medically sounding name, like Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME). Gathering data that proves or disproves a stigma can help provide patients with ammunition to officially change the name of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Along with patient advocates, a DePaul team conducted several studies to support this attempt at change.

In one of these, medical school students were given a description of a patient with common symptoms of CFS. The trainees were randomly assigned to several groups, and each group was given a different diagnostic label for the patient, such as CFS or ME. Results of these studies showed that the students’ beliefs about CFS changed depending on which diagnostic labels were used (Jason et al., 2001). When the most serious medical-sounding term, ME, was used, the patient’s condition was taken more seriously and participants were more likely to assume the illness had a real medical cause. Name-change advocates quickly cited the study’s findings, that diagnostic labels can influence perceptions, in order to justify establishing a new name for CFS.

Due to these findings and the persistence of patient advocate groups, patient groups around the world have now begun using more medically appropriate terms such as ME and ME/CFS for both their organizations and the illness (the major CFS scientific organization changed its name to the International Association of CFS/ME).

INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY: FROM HEROISM TO JUSTICE

In our work, it is important to establish collaborative relationships with stakeholders and communities. Collaboration involves building relationships, particularly using methods that focus on respect for diversity, differences, trust, and leaving space for accountability and responsibility. To be successful, it is first important to understand the culture and context in which members of the community operate, engage in the process of making sense of the problem, and collectively explore solutions. Community psychologists, working nationally or internationally, are committed to raising critical awareness to undermine abusive conditions.

Another danger in our work with communities has been referred to as heroism. Heroism refers to a person working with underprivileged, disadvantaged populations and indicates that he or she has solutions to the community’s problems. Sometimes you see this in journals or presented on television or travel documentaries (e.g., Parts Unknown with Anthony Bourdain). This is something that community psychologists avoid when working with communities.

As an international community psychologist, it is important to be aware of other ways of seeing and being (Schostak & Schostak, 2008). Doing Community Psychology means creating a relatively safe space to speak up and share experiences and feelings. Working in international settings is all about having the ability to listen and acknowledge the capacities of others to solve their problems. However, it is important to not allow those with power, representing the status quo, to impose their values on communities (Prilleltensky, 1994).

In this sense, our work is of an ideology designed to alleviate the suffering of oppressed people, serve the refugee camps and marginalized communities, and respond to the need for psychosocial support and services.

THE CHALLENGES OF DOING INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY

As you are perhaps becoming aware, there are unique barriers to doing International Community Psychology work. Here are just a few.

Finding Collaborators

A barrier to doing Community Psychology work is finding collaborators. As with at-home Community Psychology, the key to finding collaborators is to reach out and build networks. Attending local and international conferences and seeking out foreign attendees are also winning strategies. Both APA and SCRA offer domestic and international travel grants for students to attend such conferences. Other sources of contacts and collaborators are workshops and presentations on campuses by international organizations such as nongovernmental organizations, charitable and nonprofit organizations. These may include religious organizations, businesses, and international professional associations.

Another way is to participate in international special issues of journals. Doug Perkins of Vanderbilt (see Case Study 4.1) notes that researchers in other countries tend to be more open to international collaborations—perhaps even more open than US-based researchers. If you read an interesting journal article—contact the author! Because these researchers are typically in non-English speaking countries, they may wish to collaborate with you to improve their language skills.

If visiting a country on holiday or excursion, we advise searching for research in that country or viewing the local university faculty listing of the psychology department beforehand. Of course, before visiting you should contact people in writing with a brief introduction of yourself and politely initiate contact while in-country.

Language Barriers and Communication

Another obvious barrier to doing Community Psychology work is not speaking the local language. You might be surprised to learn that English is the standard language used in international conferences. According to the interviewees in Harvey and Mihaylov (2017), learning the local language is not necessary, and often collaborators speak English and wish to develop this skill with international collaborators. However, learning some of the local languages is always appreciated and shows respect.

You might also inadvertently use offensive language—or hear it. Remember, international perspectives mean that people view the same things differently, and these discomforts are part of the experience. If used as “teachable moments” they will become enriching and eye-opening. In many parts of Eastern Europe, the English word “community” evokes something negatively associated with life under repressive communist regimes that ended in 1989-1991. This negative association led to the decision to name a Community Psychology class “The Psychology of Social Change,” which is taught to English-speaking undergraduates from the region at the American University in Bulgaria.

Political Barriers

One of the ways that community psychologists work to promote social change is through public policy. In many cases, this means working with local and national governments. In international settings, positive and negative views about politics, and of what governments can and cannot do because of resources, priorities, levels of accountability, and how they are viewed by the community will all have an impact on “how things are done around here.” This awareness is crucial—if political action is viewed as futile or hopelessly corrupt, then perhaps a more grass-roots approach is necessary.

In addition, International Community Psychology “guests” may have widely varying influences on public policy—from being welcomed as an “outside expert” to being viewed as a “foreign intruder.” The individual international community psychologist may or may not have an influence on how they are perceived by the locals or the government. Again, knowing the context and depending on local experts is recommended.

INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY PSYCHOLOGY AS A METHOD TO GAIN PRACTICAL SKILLS

Experienced International Community Psychology practitioners report that their international work creates opportunities for creativity, reflection, and self-discovery, as well as striving toward new visions of human life that could not be accomplished in one’s native setting. Below is a list of practical skills and examples from doing International Community Psychology work.

Deeply Understanding Context and Change

The former poet laureate Robert Pinsky (2002) wrote: “American culture as I have experienced it seems so much in process, so brilliantly and sometimes brutally in motion, that standard models for it fail to apply.” Pinsky’s observation suggests that cultural change requires two fundamental attributes: knowing what is possible, and that the ability and speed of cultural change is also a part of the culture.

International Community Psychology teaches us that all issues of social change involve cultural changes. What does this mean in practical terms? It means that the timescale of International Community Psychology interventions might be years, or even intergenerational. It means working on small, incremental, bottom-up changes rather than large-scale, top-down changes. It certainly means taking the long view, as advocated by Jason (2013).

Developing Cultural Competency

Cultural competence is not only working with our collaborators and participants; it also applies to the field of Community Psychology itself. And we stated earlier, International Community Psychology lends itself to exposing one’s competence (or need to develop more thereof) as a fundamental benefit of International Community Psychology work.

The value of International Community Psychology is to experience radically new contexts. An international community psychologist cannot “parachute” into an international setting and expect to get things done in the way they might be accustomed to. Our field is an applied field; learning how to bring about social change in a radically different cultural context requires a lot of exploration.

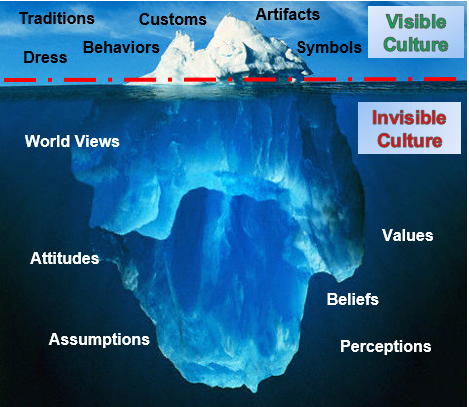

Like the diagram above, what is visible in a culture is small compared to the reality underneath the surface. The experience of working below the surface can inform community psychologists of their own deficiencies and areas for improvement. Working below the surface can remind you of your goals in the work. It teaches pragmaticism. When working in an environment where blatant corruption such as bribing is necessary, confronting the corruption as a foreign guest might leave you feeling judgmental (see ethnocentrism).

The benefit is that these experiences develop competence by relying on collaborators and local expertise to achieve the goals of the work. This helps the international researcher to develop empathy while helping to confront personal biases and limitations. Many international community psychologists learn to welcome this discomfort. If one lives like a local in the community, and embraces the ambiguity of the unexpected and unplanned, things will start to happen on their own. This reminds us to be open for opportunities for interactions with local populations, where the best information may be gathered while on a bus, waiting in line, or even when stranded. “What seems like chaos can turn into something beautiful” (Harvey & Mihaylov, 2017, p. 291).

Humility and Learning

Cultural competence is one of the integral values of Community Psychology established at the Swampscott Conference. But as the interviewees explained in Harvey and Mihaylov (2017), if you do not yet have cultural competence in an international setting, you can certainly foster cultural humility. Humility is a concept that might erroneously be conflated with humiliation. This is most emphatically not what we mean. Humility, at its simplest, is the attribute of being teachable and accepting that one has much more to learn—so much so that one is not really sure what one does not know. One of the benefits of being teachable is that it forces international community psychologists to listen and to ask questions through their collaborators. Although perhaps time-consuming, it allows for much more interaction to build valuable trust and knowledge.

Having an Impact from Small Beginnings

In International Community Psychology practice, you may be entering a community in which conditions are dire. You might witness extreme poverty, sexism, or indifference to the suffering of others. You might see blatant corruption of government officials and the effects of that corruption on the community. Remember, people live their entire lives in conditions very different from your own. You might experience feelings of guilt and become acutely aware of the privilege of being a person living in the “wealthy” US.

As you will learn from this book, Community Psychology is unique in its approach, but it is not as well-known as Clinical or Social Psychology. This is especially true in international settings, where even the word “psychology” may mean “mental illness” and have the stigma associated with that label.

According to Perkins (2019), Community Psychology is represented least in countries where it is needed the most. The good news is that people need not be familiar with Community Psychology to benefit from the sort of actions, interventions, and useful knowledge community psychologists can generate. These include participatory action research, needs assessment, strengths-based approaches, and program evaluation. Given the right collaborators and approaches, the welcome an international community psychologist may experience on entry into a community can be overwhelmingly positive (Harvey & Mihaylov, 2017).

In addition, there is an advantage to starting from small beginnings. A small beginning in International Community Psychology work can have a real impact on a school, village, family, or community. Like a tiny mustard seed growing into a huge tree, a small project can lead to significant developments as people become empowered and begin to take control of their lives and communities. Very often in international work, you have the opportunity to create something brand new and see the effects firsthand. This is what makes international work unique and satisfying.

STARTING YOUR INTERNATIONAL ADVENTURE

A good place to start is the SCRA International Committee to explore the international experiences of others. These are invaluable for connecting Community Psychology students and researchers from all over the world. APA’s Division 52: International Psychology promotes global perspectives on mental health and research.

If you want to see international research in action, we advise visiting the Community Innovators page on the Community Tool Box and clicking on a pin on the map.

SUMMING UP

International work is rewarding and challenging. Regardless of whether working “at home” or internationally, the principles are the same: we cannot ignore injustices just because they occur far away from home; besides violating community psychologists’ core values, all injustices—including asylum seekers fleeing from war and armed violence, enforced poverty, and sexual slavery—will eventually affect us at home too. We must consider the global context to address the root causes of local social problems. For every complex problem, there is no simple, easy, or right solution. According to Steve Herbert (2001), complex problems invariably require complex and difficult solutions. Community psychologists who foster such “brave spaces” can awaken liberation knowledge and practices anywhere they work.

Culture and context is the water in which we International Community Psychology fish swim. This view is that culture is not a “thing”—it is a process that influences how we see others and how others see us (Geertz, 1973). International Community Psychology work can reveal strengths in us and in our international collaborators that may not have been discovered otherwise. Taking a risk by being a fish in different waters can accomplish this.

We wish you happy swimming!

Critical Thought Questions

- How do you think community psychology practitioners can avoid cultural imperialism when working as guests in international settings?

- Think about a “top-down” approach for social change with political operatives in a community – an arguably powerful and enviable position in the U.S. Now think about how an International Community Psychology would appear to community members in a low-trust, politically corrupt culture using the same top-down approach?

- Being “needy” in international settings in terms of language, local guides, cultural navigations, and contacts present significant barriers. Can you think of ways in which these same barriers are also opportunities to establish deep collaborations?

- Group exercise: In groups of three to five people, and then select one or two of the Community Psychology Foundational Principles. Then, as a mental exercise, “parachute” into someplace in the world you know something about – or nothing about it at all. Discuss what would change, what concepts would need most explanation and/or translation, and/or who could be your collaborators in discovering what local people think of the Principle. List these and present them to your class.

Take the Chapter 4 Quiz

View the Chapter 4 Lecture Slides

____________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Burchett, H. E. D., Lavis, J. N., Mayhew, S. H., & Dobrow, M. J. (2012). Perceptions of the usefulness and use of research conducted in other countries. Evidence and Policy, 8(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426412X620100

Fetterman, D., & Wandersman, A. (2007). Empowerment evaluation: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. American Journal of Evaluation, 28(2), 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214007301350

Geertz, C. (1973). Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. In The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays (pp. 3-30). Basic.

Harvey, R., & N. Mihaylov (2017). Doing Community Psychology internationally: Lessons learned in the field. In J. J. Viola & O. Glantsman (Eds.), Diverse careers in Community Psychology. Oxford University Press.

Herbert, S. (2001). Policing the contemporary city: Fixing broken windows or shoring up NeoLiberalism? Theoretical Criminology, 5(4), 445-466.

Jason, L. A. (2013). Principles of social change. Oxford University Press.

Jason, L. A., Glantsman, O., O’Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. (2019). Introduction to the field of Community Psychology. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/intro-to-community-psychology/

Jason, L. A., Taylor, R. R., Stepanek, Z., & Plioplys, S. (2001). Attitudes regarding chronic fatigue syndrome: The importance of a name. Journal of Health Psychology, 6, 61-71. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910530100600105

Perkins, D. D. (2019). The global development of applied community studies: Comparison and evaluation of trends in psychology, sociology, social work and other community sciences. Published in Liminales: Escritos sobre Psicología y Sociedad / Writings on Psychology and Society By the Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad Central de Chile. Based on invited addresses at UC-Chile: Santiago and La Serena, Chile (October 1-2, 2018) and at the Biennial Conference of the Society for Community Research and Action (2017: Ottawa, Canada) in recognition of the 2016 SCRA Award for Distinguished Contributions to Theory and Research in Community Psychology. https://www.researchgate.net/project/Global-Development-of-Applied-Community-Studies

Pinsky, R. (2002). Democracy, culture and the voice of poetry. Princeton University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7rxs5

Prilleltensky, I. (1994). The morals and politics of psychology. State University of New York Press.

Reich, S. M., Riemer, M., Prilleltensky, I., & Montero, M. (2007). International community psychology: History and theories. Springer Science + Business Media.

Schostak, J., & Schostak, J. (2008). Radical research: Designing, developing, and writing research to make a difference. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Shweder, R. (1990). Cultural Psychology – what is it? In J. Stigler, R. Schweder, & G. Herdt (Eds.), Cultural Psychology: Essays on Comparative Human Development (pp. 1-44). Cambridge University Press.

Vassileva, J., Petkova, P., Georgiev, S., Martin, E. M., Tersiyski, R., Raycheva, M., . . . Marinov, P. (2007). Impaired decision-making in psychopathic heroin addicts. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86(2-3), 287-289.

Zippay, A. (1995). The politics of empowerment. Social Work, 40(2), 263-267.