6

Ed Stevens and Michael Dropkin

Chapter Six Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Know how to use an ecological lens in guiding community research

- Identify the role of ethics in Community Psychology research

- Differentiate between qualitative versus quantitative methods

- Understand the utility of mixed methods research

In psychology, we generally call the results of our research “findings” or “outcomes.” In this chapter, we will explore how a Community Psychology lens can help shape our research and ultimately influence our findings and outcomes. We will learn how the way we measure programs cannot exist in a vacuum, and therefore we must consider the context and environment of any situation. Take this for an example: a number of years ago in a low resourced urban community, a mental health professional approached community and school leaders with an innovative program aimed at dealing with the problem of youth substance use. They agreed to use a preventive school-based intervention, and after it was launched, the research outcomes were very successful (i.e., youth substance use was reduced). However, funding for the program dried up after two years, and the mental health professional left the community when he no longer had the financial resources to mount the intervention. The school and community leaders were disappointed as they felt it had helped their youth. The mental health professional later published the outcomes in a scientific journal and described the intervention as successful. However, the community members were bitter about the program shutting down because they did not have the resources or skills to sustain it. When another mental health professional approached the same community leaders a year later with another innovative idea for a preventive program, the community was no longer receptive.

IS A COMMUNITY INTERVENTION SUCCESSFUL?

You might be wondering, was the example above considered a successful intervention? To answer this question, we need to specify the essential characteristics of evidence when measuring factors of success. Not all evidence is created equal, as the example above indicates. The best and most useful evidence is relevant, credible, believable, and trustworthy. Additionally, there are various lenses we might look through to decipher the evidence gathered from the example. From a traditional perspective, the intervention was a credible success, as youth experimented less with drugs after the intervention took place. However, from a Community Psychology perspective, the intervention was not successful as the program was not sustained, and even more important, the community members became less trusting, less open, and less willing to collaborate with others from outside their community. It is only by adopting a more ecological perspective that we can understand that interventions have impacts on individuals, groups, organizations, and communities, and even if there are positive outcomes for the youth recipients of an intervention, we must also assess a community’s receptivity for future efforts. In other words, Community Psychology would argue for broadening our research objectives to gauge the community members’ relationship to those who brought the intervention into their schools, including whether they considered them trustworthy.

To summarize, although it is important that youth might have learned certain positive skills from an intervention, it is also crucial to examine the larger context that involves whether community members feel competent to bring about effective and sustainable changes. The goals of our research need to go beyond measuring skills or abilities within youth in order to assess whether the interventions have influenced higher-level ecological issues. In this chapter, we will learn that research can be used to add to or modify our beliefs and understanding, especially when we consider how Community Psychology focuses on people and their ecological context.

HOW EVIDENCE CHANGES BELIEFS

The introduction of new or additional evidence can challenge existing beliefs. Consequently, there are a number of examples of research evidence that have led to changes in beliefs and behaviors, as well as the way we educate people on certain concepts. For example, as indicated in Chapter 1 (Jason et al., 2019), up until the 1960s, television, radio, and print ads encouraged adults to smoke. An example of this can be found in “The cigarette preferred by doctors” video advertisement above. Later, in 1964, the US Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health reviewed over 7,000 research articles as a basis for the report, which concluded that smoking was a cause of lung cancer and chronic bronchitis. Important criteria for evidence at the time included that it was replicable and reliable. Smoking was assessed as a health hazard by checking causes of death, looking at the current health of smokers versus non-smokers, monitoring smokers’ versus non-smokers’ health over time, etc. The strongest case occurred after many investigations using multiple methods, which found similar or supporting results. After the Surgeon General’s Report in the US, policies slowly began to change regarding cigarettes and smoking. For example, advertising was significantly curtailed, cigarettes were subject to extensive state and federal taxation, and there were new regulations to reduce minors’ ability to purchase tobacco from retail establishments. As a result, rates of tobacco use declined over time.

SCIENTIFIC PROCESS

You may have encountered the scientific process in your early schooling, and maybe you were even asked to use “description” to support conclusions that you came to. But how do we interpret and draw conclusions using the research we collect? Let’s use an example to illustrate what the term “describe” means in the research process. A description could involve the number of people living in poverty, but the exact boundaries must be set for what income falls above and below the poverty line. Another example involves describing what behaviors and characteristics qualifies someone as misusing drugs. In other words, what is the definition of “misuse of drugs”? Clearly, alcohol and tobacco kill more people than all other drugs combined, and yet both of them are legal. If you define something by whether it is legal or not, there might be varying standards in different settings. For example, in the US using heroin is illegal, so it would be thought of as “misuse of drugs,” but in the Netherlands, a government-sponsored heroin distribution program began in 1988; therefore, heroin use in the Netherlands is not illegal. In describing a social or community problem, it is apparent that cultural and societal norms need to be considered. Traditional researchers might ignore these important influences, but Community Psychology researchers would put considerable efforts into understanding the politics and values that surround and give meaning to the behaviors and conditions we intend to change.

In addition to initially describing and determining how to measure a social or community problem, research also investigates how the problem or issue is associated with other behaviors. For adolescent misuse of drugs, a traditional researcher might investigate how it is related to family history, age at first use, mental health status, etc. However, a community psychologist may focus on peer use as well as locations within the community where alcohol, drugs, and tobacco are made available to youth. As indicated in Chapter 1 (Jason et al., 2019), if a school-based tobacco prevention program is launched, but youth in the community have easy access to commercial sources of cigarettes at gas stations and liquor stores, the youth receive mixed messages that compromise the outcomes of the school-based tobacco reduction interventions. Again, community psychologists give considerable weight to these types of ecological variables when trying to understand the various environmental influences on youth behavior.

Being able to explain why certain people develop drug misuse behaviors can be complicated as well and involve many factors that need to be considered when conducting research. Many traditional psychologists would focus on trying to understand biological and psychological reasons for substance use (such as depression or feelings of isolation). Community psychologists, on the other hand, would be more inclined to examine norms and opportunities within the environment. For example, if youth in a neighborhood admire apparently wealthy drug dealers who engage in illegal activities, then this risky environment and these inappropriate role models could be some of the primary reasons for increased illegal drug use. To the extent we can describe, predict, and explain why misuse of drugs occur, we are more likely to develop effective Community Psychology based interventions which deal with factors beyond the traditional individual level of analysis.

RESEARCH AND ETHICS

Performing Research

The Belmont Report (1978) outlined basic ethical principles and applications for research. The three major ethical principles are respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. When seeking institutional approval for research with human subjects, these three areas are addressed in the application.Once again, most traditional researchers focus on individual factors (e.g., level of self-esteem, mental health issues) when considering these areas, and they would assure that youth in a preventive program have informed consent to be involved in the intervention. Community psychologists would also be concerned with ecological factors. For instance, let’s consider college students being trained to provide psychiatric ward patients with mentoring and social support. If the hospital setting was poorly run and degrading, and provided limited opportunities for skill development to prepare the patients to ultimately return to the community, this mentoring program would be considered ineffective and even unethical. If the setting’s abusive features were not addressed, then the intervention would not be able to successfully help patients reintegrate back into the community.

Professional ethics from the American Psychological Association (2003) also indicate that mental health care professionals should have adequate skills and abilities for the roles in which they portray themselves as competent. For traditional psychologists, this might involve being knowledgeable about current testing and therapy techniques. For community psychologists, who often work with community-based samples of individuals who have been marginalized or who have suffered other systemic disadvantages, it might be more complicated, as these populations warrant extra care. For example, criminally justice-involved individuals who are exiting prison need more than aptitude tests and one-on-one therapy, as their greatest needs after leaving jail are housing and decent jobs. Community psychologists might not be trained to provide housing or jobs; however, this is where collaboration comes into play. Community psychologists would partner with community-based organizations which have the skills and competencies to provide ex-offenders opportunities for inexpensive housing and jobs. Thus an ecological perspective, as illustrated throughout this book, would focus our efforts on providing resources and changing the environment in order to provide these vulnerable individuals with concrete opportunities to successfully transition back into society.

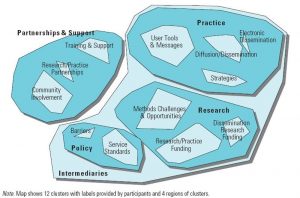

Finally, the Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA) also has specified ethical practice competencies for professionals (Dalton & Wolfe, 2012). Some of these include recognizing the influence of one’s personal background on the collaboration, so if one is from a privileged group, this could have an influence when working with community members who did not have such advantages. One essential practice competency in the field of Community Psychology is dissemination. Dissemination is the deliberate sharing of research findings to groups and communities that would benefit from said findings. Along with dissemination is implementation, which takes dissemination a step further. Implementation is the adoption of evidence-based interventions with the goal of better serving the specific population. It is most helpful to develop a professional network in order to seek consultation and advice regarding these complex issues that are being encountered in analyzing social problems as well as implementing community-based interventions.

Research evidence also informs us as to whether our efforts actually adhere to these ethical standards, and an ineffective prevention program that consumes resources (e.g., time and money) may be considered unethical, as the case study below illustrates.

Case Study 6.1

A Cautionary Tale: Drug Abuse Resistance Education

The drug prevention program Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) began in the mid-1980s in Los Angeles schools, and soon was implemented nationally. During the 1990s and early 2000s, roughly 75% of students in the US were taught using this D.A.R.E. program to prevent drug use. However, research performed as early as 1994 suggested D.A.R.E. was ineffective, and by 2004, it became clear D.A.R.E. did not work (West & O’Neal, 2004). For more than 20 years, tens of millions of students were “trained” in D.A.R.E. and billions of dollars were spent on a useless program. Parents, students, and schools were, in effect, misled by “experts.”

The D.A.R.E. example demonstrates how best intentions are not sufficient in performing ethical practice, as well as shows the importance of evidence in evaluating whether harm has occurred. Without the means, resources, or system to evaluate the impact of a program, ethical concerns go unaddressed. Rather than working separately from community activists and organizations, community psychologists are trained to evaluate and conduct research with members of a community (see Chapter 7; Wolfe, 2019).

Other research issues endorsed by SCRA (2019) include active collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and community members. This work is undertaken to serve those community members directly concerned, and should be guided by their needs and preferences, as well as by their active participation. This standard recognizes the importance of the population’s voice(s) in developing and executing a research plan that has the greatest likelihood of improving the population’s well-being and minimizing harm. This principle is one of the core values of Community Psychology, and it is often referred to as community-based participatory research. Nevertheless, there will be times when funding sources have their own agendas which may not accurately reflect a population’s needs, and this can pose unique challenges for those within the field of Community Psychology. In addition, the SCRA principles embrace multiple methodologies to best generate knowledge. These attributes are more likely to lead to many studies being conducted over an extended period of time, and the development of evidence-based practices to achieve improvements.

Ethics are important in the design and performance of research. Community Psychology reduces risks by valuing the diversity of methods, encouraging collaboration and participation, seeking to serve others, and focusing on the issues needing to be addressed by the community.

ELEMENTS OF RESEARCH DESIGN

The purpose or objectives of the research generally define the major elements of an investigation. Based on their goals and objectives, community psychologists develop a research design to best conduct their investigation. It’s important to understand that the scope of research encompasses flexibility and creativity. The basic process can be thought of as trying to achieve an objective, as well as considering what resources and sequence of activities will result in a likely success. Community psychologists specify why the research is important, determine whether the design is likely to result in credible evidence, and secure the collaboration and/or approval of stakeholders. Some of the major design elements include:

- Unit of Analysis— is the study on the individual, group, setting, community, or societal level?

- Population of Interest— is the study made up of adults, individuals meeting criteria, organizations, schools, towns, or some other group?

- Sample Recruitment— how do we get members of the population of interest to participate in the study?

- Data Collection— how does information get collected?

- Time— is the study conducted at a single time point (Cross-Sectional) or at multiple observations over time per unit of analysis (Longitudinal)?

- Design— is the study observational (with no intervention) vs. experimental (with intervention)?

- Control— does the study have a control group or is there no control group?

- Power— does the study have enough participants for the research to result in credible evidence?

- Measurement and Data Structure— does the study use a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods approach? (See below)

SCRA has identified five foundational competencies that underlie all areas of research, including specifying research questions, engaging in participatory community research, managing collaborations, developing community change models, and evaluating programs. Other competencies are in areas of research design (e.g., survey design, sampling) and data analysis (Haber et al., 2017).

QUALITATIVE

RESEARCH METHODS

Qualitative methods are very useful in the early stages of defining the topic of interest and selecting measures. This type of research usually utilizes relatively small sample sizes (less than 30) to allow an in-depth inquiry per individual. Thus, individual cases have significant weight. Qualitative data are usually collected through interviews, observation, or analysis of archival content. The interview may be unstructured (having minimal questions or anchoring by the interviewer) or structured (specific topics and questions that are consistent across the sample). The content of either interviewing or observing then undergoes analysis, and this process is how insights are formed that may be more generalizable than a single narrative.

Many analytic approaches are used in qualitative research. Four common methods are ethnography, phenomenology, grounded theory, and content analysis. Each of these has a different focus but they all place value on the “voice” of the individual being studied. The rich and complex information inherent in qualitative content should be “listened” to very closely before any sort of evaluation or judgment is made.

Ethnography, which has its roots in anthropology and cultural studies, seeks to understand the culture or ties of a group or community from an insider’s perspective. The method used is participant observation, as shown in Figure 1, and this results in an in-depth written account of a group of people in a particular place, such as a rural area that involves migrants and farming. Additionally, this method can also focus on an aspect of contemporary social life. As an example, a community psychologist may want to better understand the operation and benefits of a cancer survivors self-help group. Ethnography may be a good analytic approach to understanding the culture, attitudes, behaviors, and benefits that group membership signifies.

Phenomenology focuses on the individual and is directed to examine a person’s narrative to capture their perceptions and lived experiences. The researcher is often thought of as an “indirect” participant due to the coding and interpretation processes involved because the goal is to expose these perceptions and experiences as unfiltered as possible. In other words, there is an attempt to set aside any preconceived assumptions about a person’s feelings, thoughts, or responses to a particular issue. Across multiple participants, common themes may emerge, but often the real insights occur from the variability and range of lived experiences within a shared context. For example, a researcher may find a theme of “to feel better” when investigating reasons for youth drug use.

Grounded theory focuses on using unstructured interviews to formulate theory that emerges from the data. The general aim is to compare and code data when interviewing participants so that an updating of what “explains” the data emerges and eventually stabilizes. When no new set of ideas or theory emerges, data collection can be halted. Guidelines would suggest 10 to 25 in-depth interviews for coding. The most important perspective of grounded theory is that the data speaks for itself, and the researcher constructs theory from the interviews and without imposing their theories on the participants. This method has been most helpful in uncovering social processes, which are social relationships and behaviors of individuals in groups.

Content analysis includes an array of techniques for investigating material which may be text, photographs, video, audio, etc. The objective is to use a replicable, standardized process that reveals meaningful insights and patterns. Content analysis can involve text analysis where computer algorithms manipulate text to extract structured information that may be interpreted. An example of content analysis is PhotoVoice. This is a participatory, qualitative research method where individuals tell “their story” through photographs as indicated in Case Study 6.2.

Case Study 6.2

Content Analysis with a Participatory Process

PhotoVoice based research in Hawaii involved participants who were residents of Housing First (see Chapter One). Individuals took photographs and/or aided in interpretation as to their experiences in homelessness and Housing First. Fourteen major themes were developed after a participatory process of coding and summarizing findings. These included opportunity to rest, privacy, opportunity to reconnect socially, and improved mental health outcomes (greater hope, self-efficacy, and self-esteem). These findings were useful to researchers exploring different types of housing models for homelessness (Pruitt et al., 2018).

QUANTITATIVE

RESEARCH METHODS

Quantitative methods involve being able to count or quantify something. Of course, you have to be able to define the “something” but quantitative methods can help with that as well. Even the simplest of quantitative studies can have great value—for example, having a population list their top ten problems and rank them may provide greater insight than having an outside researcher come in and survey the population on a researcher-priority problem.

In Case Study 6.3 below is an example of this type of quantitative research, using what is called a randomized design where some individuals are provided the intervention and some are not, and then both groups are followed over time.

Case Study 6.3

A Quantitative Evaluation of a Home Visitation Program

A home visitation program was developed for at-risk low-income first-time pregnant women. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The first group received services such as transportation to prenatal care, routine child development screening, and referrals. In the experimental group, participants received the same services and, in addition, nurses conducted home visits during the prenatal period through early childhood. A 15-year follow-up study showed that the outcomes of the home visit group were fewer unwanted pregnancies, less use of welfare, and reduced child abuse and neglect. Additionally, the children showed fewer instances of running away from home and fewer sexual partners, as well as reduced alcohol consumption and criminal behavior (Olds et al., 1998).

The purpose of the research greatly determines the design and methods used in quantitative studies. Some common design decisions involve whether the research is:

- Observational or experimental—is there an intervention that the sample will experience?

- Cross-sectional or longitudinal—is the measurement a “photograph” capturing one moment in time or is it over time, capable of capturing change?

- Controlled—does the research include a control group? This can be very important for credibility.

- Random assignment—are participants randomized to either control or experimental conditions? If not randomized, the research is defined as “quasi-experimental” and if randomized, it is a true experiment.

- Single level or multilevel—since community psychology is interested in ecological context, clustering often occurs naturally in the data structure—think of students in a school clustered within classes.

The quantitative evaluation of interventions can encompass many methods and designs from a cross-sectional comparison post-intervention with a control group to pre-test and post-test studies with and without controls. The choice of these designs and methods is often limited by practical constraints (e.g., no access to a control group). A large effect size in a weaker design may be more convincing than a weak signal in a more sophisticated design.

MIXED METHODS RESEARCH

Research in Community Psychology encompasses a broad range of real-world, ecological contexts, and mixed methods research uses both qualitative and quantitative methods to capture this scope within the same study or project. In essence, there are many important strategies provided by both qualitative and quantitative research in helping us better understand the transactions between persons and community-based structures. Mixed methods provide ways to stay true to Community Psychology’s values by helping to amplify the voices within the lives of unheard and historically silenced communities. This type of research can increase validity because data are collected simultaneously on the same individuals and settings using independent methods of data collection and analysis. This method can help us better understand the complexity of the multiple levels of analysis, including individuals, families, groups, neighborhoods, communities, and cultures, as indicated in the following case study.

Case Study 6.4

A Mixed Methods Approach to Institutional Change

Allen et al. (2016) combined qualitative approaches with quantitative ones to enrich our understanding of a statewide network of family violence coordinating councils. Throughout the inquiry process, these authors used qualitative and quantitative methods. The methods were used in a sequential way so that one data collection method informed the next in terms of analysis and understanding of the data. For example, these community psychologists started by examining years of archival data, which then allowed them to better understand how the violence coordinating councils were associated with access to orders of protection across sites. This archival qualitative data allowed the investigators to better understand how the councils achieved positive outcomes. They then collected current data from councils, and this quantitative data showed a high degree of leader effectiveness. Qualitative interviews they conducted allowed them to better understand the roles of other council members not in the convener role. This helped them to better understand all the roles involved in building council capacity for institutionalized change efforts.

This innovative way of collecting data allows community psychologists to see research as a dynamic process, which helps uncover the texture and inner workings of how groups try to bring about important changes to their communities.

OTHER METHODS

Several other methods that are becoming increasingly useful as tools have evolved to include meta-analysis, which is a method for statistically summarizing the findings of multiple studies to quantify an average effect and identify possible predictors of variability of outcomes. A meta-analysis of primary prevention, mental health programs for children and adolescents found that very few programs reported negative results (Durlak & Wells, 1997). This research incorporated 177 studies and the findings provided strong evidence that prevention is beneficial for fostering the mental health of children. Another meta-analysis of youth mentoring programs suggested that evidence and theory-based programs did better (DuBois et. al., 2002). Overall, meta-analysis is a powerful technique to understand what past research offers as evidence. In the mentoring arena, many of these summary studies have been listed in the Chronicle of Evidence-Based Mentoring, which is a website developed by community psychologist Jean Rhodes.

Practical Application 6.1

The Chronicle

The Chronicle of Evidence Based Mentoring translates research into practice recommendations and is an important forum for researchers, practitioners, policy-makers, and volunteers. Since its launch, the Chronicle has attracted over a million views from its tens of thousands of monthly visitors and nearly 8,000 subscribers. The site features an impressive editorial board and an ever-changing array of research summaries, profiles, etc.

Geographical information systems (GIS) is a method that can be useful in identifying and measuring visual influences on a map. For example, the presence of “food deserts” (i.e., areas without access to affordable, quality food) among neighborhoods can be both visually and quantitatively understood by using mapping with analytic capabilities. The presence or absence can then be modeled with other neighborhood and demographic characteristics to better understand possible remedial policy or action. For example, Chilenski (2011) found that closeness to alcohol and tobacco retailers was a significant predictor of adolescent problem behaviors.

Social network studies provide insight on how relationships may influence attitudes and behaviors. Let’s assume Joey ends up primarily socializing with a group where most members use alcohol. We then learn that Joey begins using alcohol. Did the group influence Joey to begin using alcohol or did Joey join the group to be able to drink with others and not be negatively judged? This question of why youth take on risky behaviors is important to know for the development of interventions and policy. Below is a very practical use of social network analysis in school settings.

Case Study 6.5

A Social Network Analysis of a School-Based Intervention

Social network analysis was used with a school-based intervention focusing on improving the academic, behavioral, and social success of elementary school African American and Latino boys. The intervention included mentoring, family involvement activities, and after-school programming. The elementary school classroom teachers were supported by one or two “lead teachers,” who were meant to provide support and help with teaching strategies to improve student achievement. Social network analysis was used to help understand the teachers’ existing advice networks for spreading intervention strategies and helping document the lead teachers’ abilities to influence their colleagues. This method allowed the community psychologists to understand how the structure of teacher advice networks could either facilitate or hinder the spread of successful classroom intervention practices (Kornbluh & Neal, 2016).

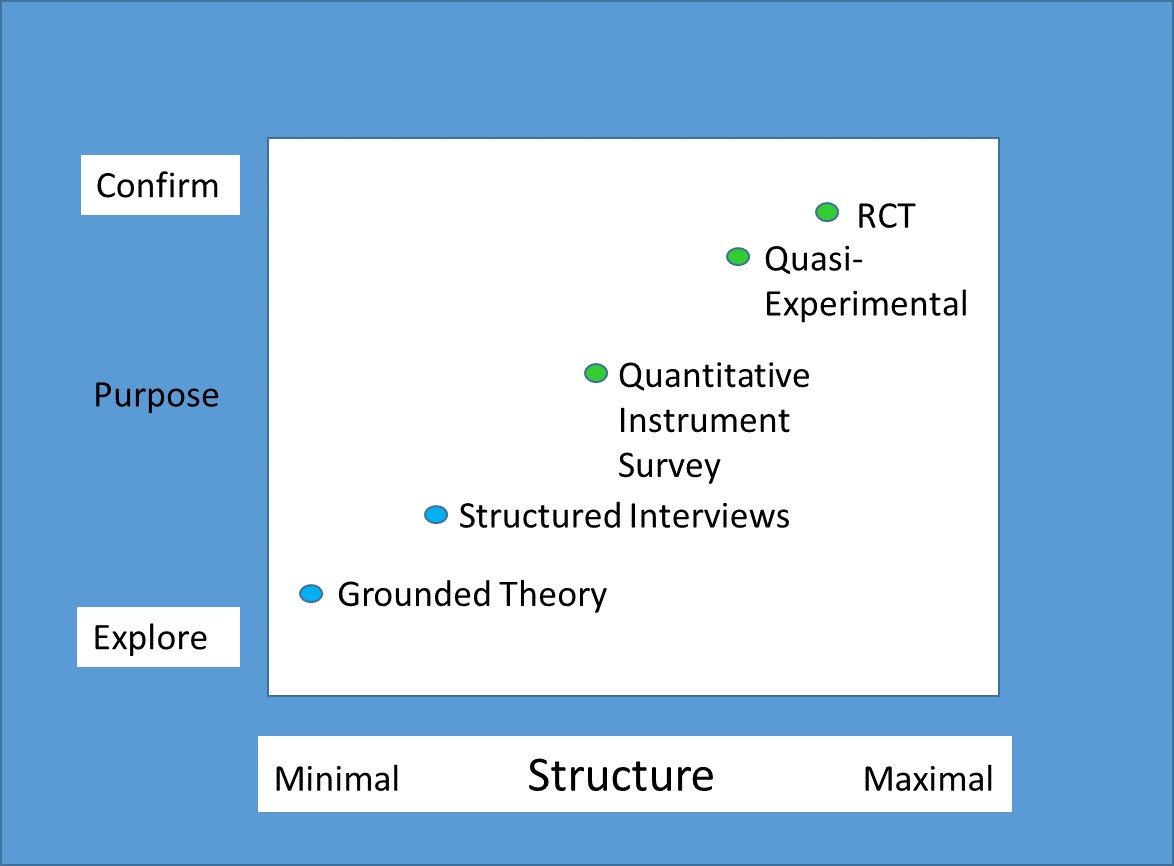

SUMMING UP

Community psychologists feel that effective research can utilize a multitude of designs and methods (Jason & Glenwick, 2012). One possible framework for conceptualizing methods maps the relationship between the degree of structure and the purpose of the research. The most tightly controlled experiments are focused on testing an intervention’s effect. While unstructured investigations are unlikely to lead to definite conclusions, they are, instead, an exploration of how things operate in the world. Figure 4 below portrays this arrangement.

Research is a powerful tool that helps us better define phenomena, measure it, make predictions about it, develop theories to explain it and put our knowledge to use for the betterment of our world. Community psychologists are trained to use research to understand what might be accounting for certain community problems like homelessness, as well as to evaluate whether particular interventions are effective. The ecological framework allows community psychologists to broaden the evaluation to include how the intervention affected a community’s commitment, openness, and readiness for change.

Community psychologists might have similar goals as community organizers, but their training in research and their ecological perspective provide them unique contributions to bringing about social justice. Ethics and research are interconnected—as good research should ethically generate evidence and evidence should guide ethical action. Clearly, the commitment of community psychologists is always “first do no harm” and that ineffective and resource-wasteful action should be stopped. There are a variety of ecological research methods that can help point the way to bringing about social justice and more equitable distribution of resources.

Critical Thought Questions

- Which research method (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, or mixed) would you utilize to research childhood obesity in the African-American community? Why? What are the ethical considerations when working with this population?

- D.A.R.E. was ineffective for numerous reasons. How would you use research to create an effective youth drug use intervention?

- Watch the video linked in the dissemination of findings section and here. There is a movement among scientists to disseminate research findings to as many people as possible. What are the possible benefits of making research findings open access? Are there any downsides?

Take the Chapter 6 Quiz

View the Chapter 6 Lecture Slides

_____________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Allen, N. E., Walden, A. L., Dworkin, E. R., & Javdani, S. (2016). Mixed methodology in multilevel, multisetting inquiry. In L. A. Jason & D. S. Glenwick (Eds.), Handbook of Methodological Approaches to Community-Based Research: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods. (pp. 335-343). Oxford University Press.

American Psychological Association (2003). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. https://www.apa.org/ethics/code

Chilenski S. M. (2011). From the macro to the micro: A geographic examination of the community context and early adolescent problem behaviors. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48(3-4), 352-64.

Dalton, J. & Wolfe, S. M. (2012). Joint column: Education Connection and The Community Practitioner. Competencies for community psychology practice. The Community Psychologist, 45(4), 8-14.

DuBois, D. L., Holloway, B. E., Valentine, J. C., & Cooper, H. (2002). Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 157–197.

Durlak, J. A., & Wells, A. M. (1997). Primary prevention mental health programs for children and adolescents: A meta‐analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 25, 115-152.

Haber, M. G., Neal, Z., Christens, B., Faust, V., Jackson, L., Wood, L. K., Scott, T. B., & Legler, R. (2017). The 2016 survey of graduate programs in Community Psychology: Findings on competencies in research and practice and challenges of training programs. The Community Psychologist, 50(2), 12-20.

Jason, L. A., & Glenwick, D. S. (Eds.). (2012). Methodological approaches to community-based research. American Psychological Association.

Jason, L. A., Glantsman, O., O’Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. (2019). Introduction to the field of Community Psychology. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/intro-to-community-psychology/

Kornbluh, M., & Neal, J. W. (2016). Social network analysis. In L. A. Jason & D. S. Glenwick (Eds.), Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. (pp. 207-217). Oxford University Press.

Olds, D., Pettitt, L. M., Robinson, J., Henderson Jr., C., Eckenrode, J., Kitzman, H., Cole, B., & Powers, J. (1998). Reducing risks for antisocial behavior with a program of prenatal and early childhood home visitation. Journal of Community Psychology, 26, 65-83.

Pruitt, A. S., Barile, J. P., Ogawa, T. Y., Peralta, N., Bugg, R., Lau, J., Lamberton T., Hall, C., & Mori, V. (2018). Housing First and Photovoice: Transforming lives, communities, and systems. American Journal of Community Psychology, 61,104-117

Society for Community Research and Action (2019). Principles. http://www.scra27.org/who-we-are/

Smoking and Health (1964). US Surgeon General’s Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. US Government Printing Office.

The Belmont Report (1978). National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Department of Health, Education and Welfare. United States Government Printing Office.

West, S. L., & O’Neal, K. K. (2004). Project D.A.R.E. outcome effectiveness revisited. American Journal of Public Health, 94(6), 1027-1029.

Wolfe, S. M. (2019). Practice Competencies. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/practice-competencies/

Thoughtful combining of qualitative and quantitative data collection methods.