15

Amie R. McKibban and Crystal N. Steltenpohl

Chapter Fifteen Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Understand why and how communities organize

- Explain bottom-up and top-down approaches to community organizing

- Understand the cycle of organizing

“The basic requirement for the understanding of the politics of change is to recognize the world as it is. We must work with it on its terms if we are to change it to the kind of world we would like it to be. We must first see the world as it is and not as we would like it to be.”

— Saul Alinsky, Rules for Radicals

At some point, everyone wants something about their community—or how their community is treated—to change. Maybe they feel a law is unfair, or wish their group had more resources. One way to accomplish community goals is to engage in community organizing, or the act of engaging in cooperative efforts to promote a community’s interests. Just as there are many things people may wish to change, community organizing comes in many shapes and forms and can be used to initiate small changes within a community or larger changes throughout society. Engaging in community organizing involves actively cultivating relationships with a number of people, some of whom may have different ideas about solutions. If it sounds complicated, that’s because it is! Thankfully, we have many examples of successful community organizing, some of which come from collaborative partnerships.

COLLABORATIVE PARTNERSHIPS

To understand collaborative partnerships, let’s first break down these two terms into their simplest form. A partnership is a mutual relationship between two or more people. This relationship can be hierarchical, as is the case between you and your boss, or equal, like the relationship between you and your co-workers. Collaboration, on the other hand, is an action. Specifically, collaboration is the action of working with one or more people to produce or create something.

Taken together, a collaborative partnership is a reciprocal relationship between two or more people with a shared goal in mind. Collaborative partnerships are often dynamic, characterized by constant change, activity, or progress. Thinking about what you have read so far, what are some examples of collaborative partnerships you have encountered in the case study boxes throughout this book? Before reading further, take a moment to list them. Now that you have revisited the case studies and have a list of collaborative partnerships, are there commonalities between them? Do they differ from what you think of as community organizing? Often in Community Psychology, collaborative partnerships have common themes with and key differences from other forms of community organizing. Let’s take a look at some of these commonalities and differences.

Organization of Collaborative Partnerships

As you may recall from the introductory chapter (Jason et al., 2019), a major focus of Community Psychology is that of social justice. It is common for community psychologists to develop collaborative partnerships with organizations that serve oppressed groups. As cutbacks in the public sector have become more and more common the past three decades, collaborative partnerships between community psychologists and community organizations have provided one solution to dwindling resources within organizations (Nelson et al., 2001). These partnerships can also assist when the organization lacks expertise in certain areas. For example, community psychologist Amie McKibban partnered with the YMCA Caldwell Center in Evansville, Indiana to assist the organization in gathering feedback from the diverse population the center served to better meet their needs. After completing focus groups with the neighborhood residents, Dr. McKibban and her Community Psychology students developed a needs-based survey that was administered to the same residents. As a result, the center was able to write evidence-based grants and obtain funding for different types of programs that better met the residents’ needs (McKibban & Steltenpohl, 2019; see the following case study).

Case Study 15.1

The Caldwell Center Partnership

The YMCA Caldwell Center is in the Glenwood neighborhood, a racially diverse, economically disadvantaged area with 46.8% of the residents living below poverty and 53.5% having less than a high school education. The goal of working with this YMCA branch was twofold: the project aided community psychologist Amie McKibban in teaching her students real-world, marketable skills relevant to community psychological research, and the community partners received assistance in developing a tangible product that could be utilized to better serve community members’ needs. This partnership was established through the University of Southern Indiana’s Outreach and Engagement office, which is designed to connect community entities in need of services with researchers on campus. The collaborative effort rested on two demonstrable outcomes for the Caldwell Center: to provide qualitative feedback from different age groups utilizing their services (a bottom-up focus on residents’ needs) and to create a quantitative measurement tool that could be used to collect data more easily and quickly once they ended the partnership.

Bottom-Up and Top-Down Approaches

Collaborative partnerships, as illustrated in Case Study 15.1, are often more formal in nature, designed to meet a specific need of the organization, and have a specified timeline with an end goal. Although not always true, collaborative partnerships tend to take a top-down approach to social change. That is, they tend to be designed by experts or community leaders who are often not part of the community the social change will impact. Top-down approaches carry with them the benefit of expertise and legitimacy, but also run the risk of reflecting the experiences and world views of the experts. In other words, the needs and voices of the community may be lost in translation (Fawcett, et al., 1995). This approach also runs the risk of reinforcing existing power structures, and as you learned in Chapter 1, inequality in power structures is often the root cause of other problems such as poverty and income inequality.

Often, when we think of community organizing, a top-down approach isn’t the first thing that comes to mind. Although this is a beneficial approach in certain settings, sometimes the most powerful forms of social change utilize a bottom-up approach, which originate at the grassroots level. That is, they are designed by community members rather than experts or professionals. An easy way to illustrate this difference is with mental health care. Seeking the services of a therapist is a top-down approach to mental health care. You seek the expert advice of a therapist to feel better. On the other hand, self-help groups represent a bottom-up approach, where you seek the support of others with mental health difficulties to feel better.

Let’s consider another example—that of food insecurity. A top-down approach to food insecurity may include a city mandate that public schools send snacks home with children living in food deserts, where the snacks are provided by those in power. In contrast, a bottom-up approach may include a community garden initiative where local residents plant and tend to gardens, with the food being provided by those living in the food desert. This is precisely what one group of concerned citizens in Evansville, Indiana did when they started the first Urban Seeds community garden in 2005. Their efforts have since grown into a non-profit organization that serves the region of Southern Indiana. Of course, with any kind of partnership, it is important to consider the potential for iatrogenic effects, or unintended consequences. You may find it helpful to talk about values and goals early on in the process of working with community organizations and groups, looking specifically for areas of overlap and differences. It is also a good idea to define important terms, talk about how you will deal with conflict (for example, a disagreement between university researchers and the school district), and discuss how long the relationship will last. Partners should revisit these agreements to make sure any changes are addressed. See Case Study 15.2 for an example and some good ideas to consider.

Case Study 15.2

Innovative Channels of Change in California

Regina Day Langhout and her team worked with an after-school program in Maplewood, California to aid students in designing, researching, and implementing action research in their school. Students learned about research design and methodology, developed and completed actions to address their selected issues, and presented their findings. As the partnership developed, Langhout and her team ran into challenges around limited budgets, power differentials between students and their school institutions, limitations on what projects were considered “worth” pursuing, and what the “right” channels of change were. It was important for Langhout’s team to continue to communicate with students and faculty throughout the partnership and address these challenges as they came up (Kohfeldt, Chhun, Grace, & Langhout, 2011).

Now that you know the difference between these two approaches, think about changes you would like to see in your own community. What type of approach do you feel would be best to achieve that change? Sometimes figuring out which approach may be best can be difficult, and community psychologists generally agree that neither approach is best, as they both offer benefits. Whereas bottom-up approaches tend to embrace the values inherent in Community Psychology, top-down approaches are often needed for their resources—such as funding and expertise. In many cases, like the one described in Case Study 15.1, the two approaches are combined in hopes of achieving the best results.

COMMUNITY COALITIONS

Let’s go back to the things you would like to see changed in your local community. Is there something going on that seems insurmountable? Perhaps a problem that seems impossible to change? Oftentimes this is the case when we think about social problems and their solutions. Indeed, some social problems are wide-reaching and require long-term, complex solutions that extend beyond the scope of collaborative partnerships. Community coalitions, on the other hand, tend to tackle larger social issues by bringing together a representation of community citizens and organizations—both private and public—situated in a way to address large social problems at multiple levels within a community. Like collaborative partnerships, community coalitions have become more popular in recent years following cutbacks to funding for social services, therefore putting pressure on communities to do more with less (Nelson et al., 2001).

Given the organizational structure of community coalitions, members often agree upon a mission, vision, and set of shared values, all of which help coalitions write and implement action plans. These action plans help guide the coalition in their work, whether the work is carried out by the coalition itself or by affiliated organizations (Wolff, 2001a). Not only do coalitions help strengthen citizen participation, a staple of Community Psychology, they hold the potential to change policy at local and state levels, and increase community resources (Wolff, 2001b). To illustrate coalitions in action, let’s consider two very different community coalitions—one that came out of a grassroots effort to tackle a host of community issues where the work is done by the coalition itself (Case Study 15.3a), and one that developed over decades of work to decrease economic disparities, where much of the work is carried out by affiliated organizations (Case Study 15.3b).

Case Study 15.3a

Congregations Acting for Justice and Empowerment

Congregations Acting for Justice and Empowermentis an interfaith coalition comprised of 22 religious organizations in Southern Indiana. It started by members of different religious congregations coming together to better understand what community issues were mutually important to them through listening sessions, a practice that continues today and draws hundreds of community members from different congregations. Through these listening sessions, members decide on one or two issues to address throughout the year and develop an evidence-based action plan. One example of how this coalition impacted community practice was their success in reaching an agreement with three county sheriff’s offices and the city fire department to equip officers and firefighters with Narcan, a life-saving medication for drug overdoses.

Watch this this PSA on the success of a similar approach to drug overdoses in Massachusetts.

Case Study 15.3b

The Community Action Program of Evansville

The Community Action Program of Evansville is a multi-organization coalition that developed under the auspices of the City of Evansville in the 1960s with the mission of promoting economic and social self-sufficiency for the area’s racial minority populations. The coalition develops action plans under the guidance of a Board of Directors consisting of representatives from three different counties that represent both the public and private sector. Twenty-four community programs are housed under this coalition— including programs such as Head Start, Financial Literacy for Home Buyers, and Emergency Need Pantry—with multiple organizations carrying out the work. The coalition’s development of partnerships to provide affordable, apartment-style housing for multi-person households is an example of community practice.

THE CYCLE OF COMMUNITY ORGANIZING

Successful community organizing tends to follow a cycle: assessment, research, mobilization (action), and reflection (Speer et al., 1995). A student organization wanting to improve access to mental health resources on its university campus may first assess what resources already exist on campus. They may also have one-on-one or small group meetings with students, staff, and faculty to better understand their experiences. If they can, they may also do a survey of a representative sample of students. Their main questions may be things like: What issues do students face when dealing with their own mental health? Are students able to meet with counselors when they need to? Are there differences in what groups readily have access to resources? Do faculty know what the process of referring students to various resources on campus looks like?

After this assessment stage, the student organization will want to enter the research stage. Here, it will be important to meet with campus leaders to understand what funding and other resources are allocated to mental health. They may meet with the dean of students to discuss different programming goals or the counseling center to understand what mental health concerns students come into the center with most often and how those concerns are addressed. The student organization may hold public meetings on the issue for students, staff, and faculty to raise concerns or to build public support. This will help them move into the action phase.

In the action phase, the student organization may host events raising awareness of mental health concerns and how to address them, with a call for more resources on campus dedicated to helping students thrive socioemotionally. They may create and distribute a petition calling for administrators and the board of trustees to allocate more funding to hire more counselors or provide the counseling center more or updated space. They may even participate in sit-ins, march on campus, or publish opinion pieces in the student or local newspapers. With the increased use of social media, they may create a social media campaign, incorporating the use of hashtags and encouraging community members to share their stories.

After these actions have been taken, the student organization will move into the reflection stage. Here, student leaders and their allies will want to reflect on what happened. What went well? What didn’t go well? What’s next? As Saul Alinsky (1971) suggests in Rules for Radicals, ideal organizers are curious (“Is this true?”), irreverent (“Just because it’s always been this way, does that make it right?”), and imaginative (“Let’s try to come up with another way to do this!”). They have a good sense of humor, a bit of a blurred vision of a better world, and an organized personality. Nurturing these qualities would help increase the quality of the student leaders’ reflections about their experiences. As the student leaders engage in reflection, they will also be looking forward to the next assessment stage.

It is important to recognize that time may be needed for communities to see the full effects of their efforts, as systemic change often takes time. As changemakers are considering what actions to take, they should always be mindful of intended impact. What outcomes would these student leaders hope for? Perhaps the goal is shorter wait times for students needing access to services, or a reduction in the number of medical withdrawals for mental health concerns. These are easy to measure and track, assuming the students have access to these metrics. Some outcomes, however, are harder to measure: how do we measure a reduction in stigma against those with mental health-related diagnoses? For something like that, it will be important to consider change over time, both on campus and nationally. Perhaps it would be good for students to work with faculty to develop a yearly survey to estimate attitudes surrounding mental health issues and maybe even prevalence of common mental health diagnoses.

As you might be able to see, measuring impact can get complicated pretty quickly, and often requires change leaders and others to think ahead and envision what factors will positively and negatively affect their ability to judge how things have gotten better or worse as a result of the actions they take. Some of the common obstacles found when trying to measure outcomes of coalitions include:

- Issues surrounding how representative their coalition and outcomes are compared to coalitions and outcomes generally

- Control of the independent variable (the coalition)

- Identification of extraneous variables and interactions between other extraneous variables

- Figuring out what outcomes to measure and how to measure them

- Changes over time in understanding and measurement of issues, and

- Fighting the desire to present results in a favorable way (Berkowitz, 2001).

As we have learned throughout this textbook, communities can vary widely in their membership, the contexts they inhabit, and their access to resources. While the complexity of working on and measuring the impact of community work makes this work challenging, Berkowitz encourages us to rise to that challenge and find new ways to measure what we need to measure in a reasonable and scientifically valid way.

COMMUNITY ORGANIZING TECHNIQUES

Typically, when communities organize, their goals fall within two broad categories: resource provision, or ensuring a community is provided with a resource it is lacking (a form of first-order change), and transformation, or fundamentally changing a community and its structures such that resources and power are more equitably distributed (a form of second-order change; Hale, 2014). For example, a community may be interested in improving the educational outcomes of its children. If the community’s focus is on resource provision, they may push for smaller student-to-teacher classroom ratios or better pay for teachers. If the community’s focus is on transformation, they may push for a change in culture whereby community members share ownership of students’ educational outcomes with teachers and create programs that engage all members of the community.

Those who put transformational change above resource provision argue that resources are necessary for communities and community change, but without attention to changing the systems that caused the lack of resources, there is a danger of recreating systems that allow for some groups to be left behind. For instance, if a community pushes for better pay for teachers, this may benefit teachers in some schools or school districts more than others.

A key consideration for someone interested in community organizing is finding ways to keep volunteers engaged; organizations can only be as effective as their volunteers are when working together over an extended period. Some estimates suggest only one-third of first-time meeting attendees show up to later meetings (Christens & Speer, 2011). So, what factors affect whether someone stays involved? Some factors that seem to positively influence attendance include face-to-face meetings designed to build interpersonal relationships and attendance at research-related actions (see above, where we talk about the research stage of community organizing).

Capacity Building

For change to happen, a community must engage in a process known as capacity building, or a process in which communities or organizations work to improve their collective skills and resources. In other words, before actions happen, communities need to make sure they can do the things they need to do to make that action happen and sustain the results they want. These things can include tangible resources like money or space, power, leadership, or the networks of people who care about an issue.

But why is capacity building important? Engaging in capacity building can improve community readiness for members to do the things they need to do for change to happen. For example, one study of seven Kansas communities trying to reduce underage drinking found that increasing a community’s readiness through capacity building resulted in new programs, policies, and practice changes being more easily facilitated (Anderson-Carpenter et al., 2017).

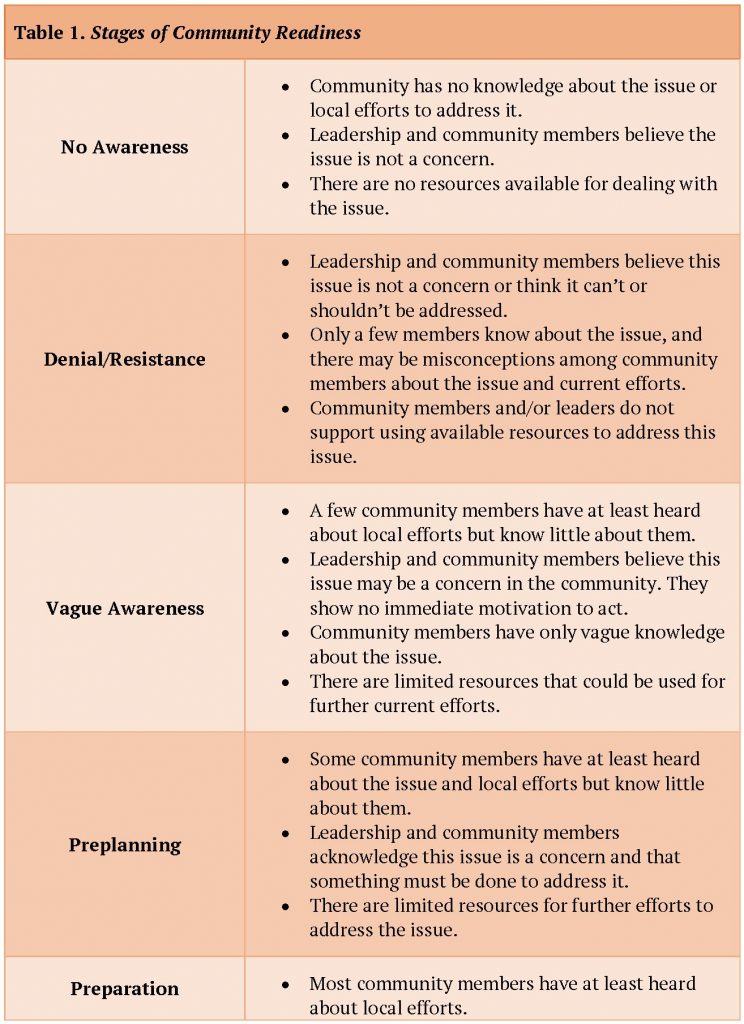

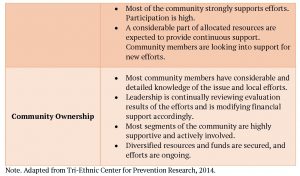

Community readiness typically moves through nine stages (see The Stages of Community Readiness above) and can increase or decrease depending on the community issue, the intensity of community efforts, and external events. Community readiness to implement interventions to prevent underage drinking, for example, may drastically increase following a terrible car accident where underage drivers had been drinking. Case Study 15.4 provides an example of community psychologists using stages of community readiness to guide their intervention.

Case Study 15.4

Community Readiness to Address Youth Tobacco Use

Jason et al. (2005) found that police departments and citizen community groups are often in different stages of readiness to change regarding reducing youth access to cigarettes. Some communities initially had minimal awareness that a problem existed locally and had no intention to invest in change, whereas others had an awareness of the problem, but no commitment to action and still others had a clear recognition of the problem and willingness to make some preliminary trials. A few other communities were ready to work hard at programs that should lead to behavior change. When working with a community in the denial stage, the Community Psychology research group often needed first to show them data from the schools to indicate that there was, in fact, a significant problem with youth smoking in their communities. The researchers also showed them data, which had been collected from the assessment of local merchants’ tobacco sales patterns, indicating that these merchants were illegally selling tobacco to minors. When the research group worked with communities in the preparation stage, police chiefs often found it helpful to rate the community’s level of readiness and where the community might like to be in a year so that the community could monitor their anticipated changes. The police chiefs’ ratings were collected by the Community Readiness Scale developed by the psychologists. The very process of discussing these issues often facilitated the communities in preparing for change and taking action. Sometimes the assessment called for the development of new tobacco control ordinances for towns, and the community psychologists were able to help the communities bring about important policy changes. It was only by understanding this readiness to take action that they could tailor the interventions to the needs of each community, and slowly work with them to become more motivated to prepare, take and maintain active social policies that could reduce youth access to tobacco and ultimately youth rates of smoking. As an example, for over a year, the research team worked collaboratively with one community to insure that this ordinance was carefully crafted and had broad community support to pass. The research team was invited to testify at a local city counsel meeting to provide evidence supporting the need for the revised ordinance. This policy development and advocacy were not required in every town, but this example shows how the team needed to carefully target their collaborative work to address the unique needs and readiness to change of each community. As a result of the success of this study and the importance of understanding community readiness, these community psychologists next used their Community Readiness Interview Scale in a larger randomized study involving 24 communities.

OTHER KEY CONCEPTS OF COMMUNITY ORGANIZING

Collective Efficacy and Participatory Efficacy

As we have learned throughout this chapter, the work of community psychologists relies heavily on community members acting collectively and intentionally (Foster-Fishman, et al., 2001). It also relies on a sense of collective efficacy, that is, the belief that the actions of the group can be successful in creating change (Zimmerman, 2000). Collective efficacy depends on many factors, such as the task at hand, access to resources, and leadership. It also depends on personal participatory efficacy—your own belief that you can effectively participate in community organizations. Both vary from situation to situation. For example, you may feel that the student group you belong to can effectively change the campus housing visitor policy (collective efficacy) and that your research skills will contribute to the group’s efforts (participatory efficacy). On the other hand, you may feel that the local homeless coalition you volunteer for will effectively establish partnerships for affordable housing (collective efficacy) but feel that you cannot contribute effectively to that mission (participatory efficacy).

Burnout in Community Organizing

We can all relate to feelings of stress. In community partnerships and coalitions, stress can lead to burnout – that feeling of overall exhaustion when there’s too much pressure (stress) and not enough sources of satisfaction or feelings of support (Maslach et al., 2000). When coalition or team members experience burnout, it comes as no surprise that the quality of their work or willingness to participate deteriorates. Researchers have found six organizational factors that contribute to burnout: high workload, little influence in decision making, inadequate rewards (e.g., compensation, recognition), lack of social support, lack of fairness, and disagreement on values (Maslach & Leiter, 2008). Effective leadership and organizational capacity can aid in preventing many of these factors, and the way in which you define the social problem and decide how to change it can make a difference.

Small Wins Approach

Think about the last time you received a high score on a paper you put a lot of time and effort into writing. It felt good, right? Successes, and the recognition of those successes, can go a long way in community organizing. When the social issue your organization is tackling has opposition, seems insurmountable, or is controversial, it is important to identify and establish small wins early in the planning phase. Organizational theorist Karl Weick (1986) found that when proposed changes are wide-sweeping and extensive, it tends to increase feelings of threat, and hence, increases a community’s resistance to change, and inaction among change agents. However, when proposed changes are small, concrete, and of moderate importance, risks seem more tolerable and manageable. These “small wins” also have the added benefit of attracting allies, preventing inaction, and deterring opponents. Take a moment to read the excerpt from Weick himself on small changes in Case Study 15.5.

Case Study 15.5

The Small Changes and Big Success of the Task Force on Gay Liberation

“The successful effort by the Task Force on Gay Liberation to change the way in which the Library of Congress classified books on the gay liberation movement is another example of a small win. Prior to 1972, books on this topic were assigned numbers reserved for books on abnormal sexual relations, sexual crimes, and sexual perversions (HQ 71-471). After 1972, the classifications were changed so that homosexuality was no longer a subcategory of abnormal relations, and all entries formerly described as ‘abnormal sex relations’ were now described as varieties of sexual life (Spector & Kitsuse, 1977, pp. 13-14). Labels and technical classifications, the mundane work of catalogers, have become the turf on which claims are staked, wins are frequent, and seemingly small changes attract attention, recruit allies, and give opponents second thoughts” (Weick, 1986, p. 42).

SUMMING UP

Community members may engage in community organizing for many reasons and in a variety of ways, though typically these goals fall within two categories: resource provision and transformation. As we learned in this chapter, collaborative partnerships may be organized using a top-down approach, where communities work with experts who are likely not a part of the affected community, or a bottom-up approach, which is driven by the community members themselves. Community coalitions tackle larger societal issues by bringing together people from across the community and its organizations.

Regardless of the exact method, community organizing often follows a cycle in which communities assess critical issues affecting the community, research causes and correlates of the issues, act through strategization and mobilization, and reflect on lessons learned. Successful organizers engage in capacity building and improving community readiness, both of which increase a community’s chances of success. Part of increasing community readiness involves building a sense of participatory and collective efficacy, which involve people’s sense that they—and their community—can change things. When things don’t go well, community members may experience burnout, or feelings of overall exhaustion that negatively impact one’s ability to engage in community organizing, which is why it’s important to focus on small wins.

Critical Thought Questions

- What skills do you think a good organizer has? Some of these skills are individual-focused (for example, organizational skills), but others might be interpersonal (e.g. collaboration).

- Imagine that a friend came to you and wanted to improve the amount, quality, and cost of vegetarian and vegan options on campus, among other environmentally-conscious actions they would like to eventually take. Take your friend through the cycle of organizing, highlighting potential opportunities and challenges that may be experienced along the way.

- Think about a social issue that is important to you. What is a bottom-up approach to address this issue? How about a top-down approach?

- What are some examples of collaborative partnerships in your local community? How about community coalitions?

- Think about the drug and alcohol prevention program in your own school. What are some possible positive and negative effects of that program?

Take the Chapter 15 Quiz

View the Chapter 15 Lecture Slides

____________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Alinsky, S. D. (1971). Rules for radicals: A practical primer for realistic radicals. Vintage Books.

Anderson‐Carpenter, K. D., Watson‐Thompson, J., Jones, M. D., & Chaney, L. (2017). Improving community readiness for change through coalition capacity building: Evidence from a multisite intervention. Journal of Community Psychology, 45(4), 486-499.

Berkowitz, B. (2001). Studying the outcomes of community-based coalitions. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(2), 213-227.

Christens, B. D., & Speer, P. W. (2011). Contextual influences on participation in community organizing: A multilevel longitudinal study. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 253-263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9393-y

Fawcett, S. B., Paine-Andrews, A., Fransisco, V., Schulz, J. Richter, K., Lewis, R., . . . Lopez, C. (1995). Using empowerment theory in collaborative partnerships for community health and development. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 677-698.

Foster-Fishman, P., Berkowitz, S., Lounsbury, D., Jacobson, S., & Allen, N. (2001). Building collaborative capacity in community coalitions: A review and integrative framework. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 241-262.

Hale, M. R. (2014). Community organizing: For resource provision or transformation? A review of the literature. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 5, 2-9.

Jason, L. A., Glantsman, O., O’Brien, J. F., & Ramian, K. N. (2019). Introduction to the field of Community Psychology. In L. A. Jason, O. Glantsman, J. F. O’Brien, & K. N. Ramian (Eds.), Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an agent of change. https://press.rebus.community/introductiontocommunitypsychology/chapter/intro-to-community-psychology/

Jason, L. A., Pokorny, S. B., Ji, P., & Kunz, C. (2005). Developing community-school-university partnerships to control youth access to tobacco. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 16, 201-222.

Kohfeldt, D., Chhun, L., Grace, S., & Langhout, R. D. (2011). Youth empowerment in context: Exploring tensions in school-based yPAR. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47(1-2), 28-45.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2000). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397-422.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 498-512.

McKibban, A. R., & Steltenpohl, C. N. (2019). Community psychology at a regional university: On engaging undergraduate students in applied research. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice, 10(2), 1-14.

Nelson, G., Prilleltensky, I., & MacGillivary, H. (2001). Building value-based partnerships toward solidarity with oppressed groups. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 649 – 677. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010406400101

Speer, P. W., Hughey, J., Gensheimer, L. K., & Adams-Leavitt, W. (1995). Organizing for power: A comparative case study. Journal of Community Psychology, 23(1), 57-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(199501)23:1<57::AID-JCOP2290230106>3.0.CO;2-9

Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research. (2014). Community readiness for community change (2nd ed.). Colorado State University.

Weick, K. (1984). Small wins: Redefining the scale of social issues. American Psychologist, 39, 40-49.

Wolff, T. (2001a). Community coalition building: Contemporary practice and research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 165-172.

Wolff, T. (2001b). The future of community coalition building. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 263-268.

Zimmerman, M. A. (2000). Empowerment theory: Psychological, organizational and community levels of analysis. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook Of Community Psychology (pp. 43-63). Kluver/Plenum.

A focus on the individual where the influence of larger environmental or societal factors is ignored.