Chapter 16: Equilibria of Other Reaction Classes

Learning Outcomes

- Write chemical equations and equilibrium expressions representing solubility equilibria

- Carry out equilibrium computations involving solubility, equilibrium expressions, and solute concentrations

Solubility equilibria are established when the dissolution and precipitation of a solute species occur at equal rates. These equilibria underlie many natural and technological processes, ranging from tooth decay to water purification. An understanding of the factors affecting compound solubility is, therefore, essential to the effective management of these processes. This section applies previously introduced chapter on equilibrium concepts and tools to systems involving dissolution and precipitation.

The Solubility Product

Recall from the chapter on solutions that the solubility of a substance can vary from essentially zero (insoluble or sparingly soluble) to infinity (miscible). A solute with finite solubility can yield a saturated solution when it is added to a solvent in an amount exceeding its solubility, resulting in a heterogeneous mixture of the saturated solution and the excess, undissolved solute. For example, a saturated solution of silver chloride (AgCl) is one in which the equilibrium shown below has been established.

[latex]\text{AgCl}\left(s\right){\underset{\text{precipitation}}{\overset{\text{dissolution}}{\rightleftharpoons}}}{\text{Ag}}^{+}\left(aq\right)+{\text{Cl}}^{-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

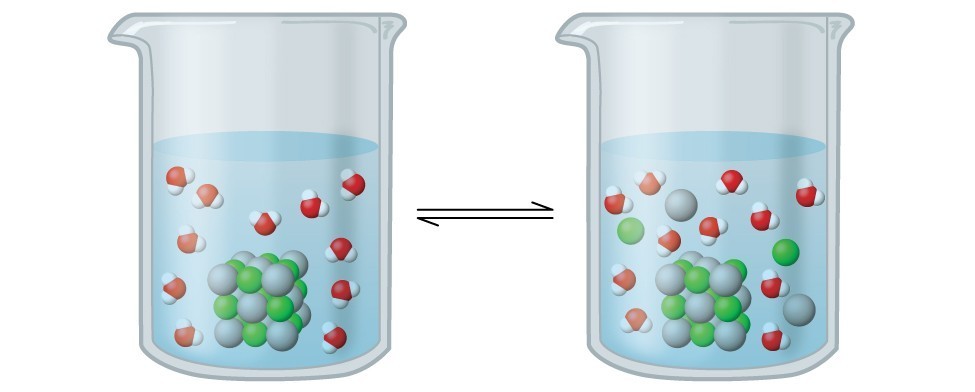

In this solution, an excess of solid AgCl dissolves and dissociates to produce aqueous [latex]\ce{Ag+}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{Cl-}[/latex] ions at the same rate that these aqueous ions combine and precipitate to form solid [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex] (Figure 16.1.1). Because silver chloride is a sparingly soluble salt, the equilibrium concentration of its dissolved ions in the solution is relatively low.

The equilibrium constant for the equilibrium between a slightly soluble ionic solid and a solution of its ions is called the solubility product (Ksp) of the solid. Recall from the chapter on solutions and colloids that we use an ion’s concentration as an approximation of its activity in a dilute solution. For silver chloride, at equilibrium:

[latex]\text{AgCl}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{Cl}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\qquad{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[{\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)\right]\left[{\text{Cl}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\right][/latex]

Recall that only gases and solutes are represented in equilibrium constant expressions, so the Ksp does not include a term for the undissolved [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex]. A listing of solubility product constants for several sparingly soluble compounds is provided in Solubility Products. Each of these equilibrium constants is much smaller than 1 because the compounds listed are only slightly soluble. A small Ksp represents a system in which the equilibrium lies to the left, so that relatively few hydrated ions would be present in a saturated solution.

| Table 16.1.1. Common Solubility Products by Decreasing Equilibrium Constants | |

|---|---|

| Substance | Ksp at 25 °C |

| [latex]\ce{CuCl}[/latex] | 1.2 × 10–6 |

| [latex]\ce{CuBr}[/latex] | 6.27 × 10–9 |

| [latex]\ce{AgI}[/latex] | 1.5 × 10–16 |

| [latex]\ce{PbS}[/latex] | 7 × 10–29 |

| [latex]\ce{Al(OH)3}[/latex] | 2 × 10–32 |

| [latex]\ce{Fe(OH)3}[/latex] | 4 × 10–38 |

Example 16.1.1: Writing Equations and Solubility Products

Write the dissolution equation and the solubility product expression for each of the following slightly soluble ionic compounds:

- [latex]\ce{AgI}[/latex], silver iodide, a solid with antiseptic properties

- [latex]\ce{CaCO3}[/latex], calcium carbonate, the active ingredient in many over-the-counter chewable antacids

- [latex]\ce{Mg(OH)2}[/latex], magnesium hydroxide, the active ingredient in Milk of Magnesia

- [latex]\ce{Mg(NH4)PO4}[/latex], magnesium ammonium phosphate, an essentially insoluble substance used in tests for magnesium

- [latex]\ce{Ca5(PO4)3OH}[/latex], the mineral apatite, a source of phosphate for fertilizers

(Hint: When determining how to break 4 and 5 up into ions, refer to the list of polyatomic ions in the section on chemical nomenclature.)

Show Solution

- [latex]\text{AgI}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons\text{Ag}^{+}\left(aq\right)+\text{I}^{-}\left(aq\right)\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Ag}^{+}\right]\left[\text{I}^{-}\right][/latex]

- [latex]\text{CaCO}_{3}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons\text{Ca}^{2+}\left(aq\right)+\text{CO}_{3}^{2-}\left(aq\right)\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Ca}^{2+}\right]\left[\text{CO}_{3}^{2-}\right][/latex]

- [latex]\text{Mg}\left(\text{OH}\right)_{2}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons\text{Mg}^{2+}\left(aq\right)+2\text{OH}^{-}\left(aq\right)\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Mg}^{2+}\right]\left[\text{OH}^{-}\right]^{2}[/latex]

- [latex]\text{Mg}\left(\text{NH}_{4}\right)\text{PO}_{4}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons\text{Mg}^{2+}\left(aq\right)+\text{NH}_{4}^{+}\left(aq\right)+\text{PO}_{4}^{3-}\left(aq\right) \,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Mg}^{2+}\right]\left[\text{NH}_{4}^\text{+}\right]\left[\text{PO}_{4}^{3-}\right][/latex]

- [latex]\text{Ca}_{5}\left(\text{PO}_{4}\right)3\text{OH}\left(\text{s}\right)\rightleftharpoons5\text{Ca}^{2+}\left(aq\right)+3\text{PO}_{4}^{3-}\left(aq\right)+\text{OH}-\left(aq\right)\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Ca}^{2+}\right]^{5}\left[\text{PO}_{4}^{3-}\right]^{3}\left[\text{OH}^{-}\right][/latex]

Check Your Learning

Now we will extend the discussion of Ksp and show how the solubility product constant is determined from the solubility of its ions, as well as how Ksp can be used to determine the molar solubility of a substance.

Ksp and Solubility

The Ksp of a slightly soluble ionic compound may be simply related to its measured solubility provided the dissolution process involves only dissociation and solvation, for example:

[latex]{\text{M}}_{p}{\text{X}}_{q}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons p{\text{M}}^{\text{m+}}\left(aq\right)+q{\text{X}}^{\text{n}-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

For cases such as these, one may derive Ksp values from provided solubilities, or vice-versa. Calculations of this sort are most conveniently performed using a compound’s molar solubility, measured as moles of dissolved solute per liter of saturated solution.

Example 16.1.2: Calculation of Ksp from Equilibrium Concentrations

Fluorite, [latex]\ce{CaF2}[/latex], is a slightly soluble solid that dissolves according to the equation:

[latex]{\text{CaF}}_{2}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{2F}}^{-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

The concentration of [latex]\ce{Ca^2+}[/latex] in a saturated solution of [latex]\ce{CaF2}[/latex] is 2.15 × 10–4M. What is the solubility product of fluorite?

Show Solution

According to the stoichiometry of the dissolution equation, the fluoride ion molarity of a [latex]\ce{CaF2}[/latex] solution is equal to twice its calcium ion molarity:

[latex][\text{F}^{-}]=(2\text{ mol F}^{-}/1\text{ mol Ca}^{2+})=(2)(2.15\times{10}^{-4}M)=4.30\times{10}^{-4}M[/latex]

Substituting the ion concentrations into the Ksp expression gives

[latex]{K}_{\text{sp}}={\text{[Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\text{]}\text{[}{\text{F}}^{-}{]}^{2}=\text{(2.15}\times {10}^{-4}\big){\left(4.30\times {10}^{-4}\right)}^{2}=\text{3.98}\times {10}^{-11}[/latex]

Check Your Learning

Example 16.1.3: Determination of Molar Solubility from Ksp

The Ksp of copper(I) bromide, [latex]\ce{CuBr}[/latex], is 6.3 × 10–9. Calculate the molar solubility of copper bromide.

Show Solution

The solubility product constant of copper(I) bromide is 6.3 × 10–9. The reaction is:

[latex]\text{CuBr}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Cu}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{Br}}^{-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

First, write out the solubility product equilibrium constant expression:

[latex]{K}_{\text{sp}}=\text{[}{\text{Cu}}^{\text{+}}{]\text{[}\text{Br}}^{-}\text{]}[/latex]

Create an ICE table (as introduced in the chapter on fundamental equilibrium concepts), leaving the [latex]\ce{CuBr}[/latex] column empty as it is a solid and does not contribute to the Ksp:

At equilibrium:

[latex]{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Cu}^{+}\right]\left[\text{Br}^{-}\right][/latex]

[latex]6.3\times {10}^{-9}=\left(x\right)\left(x\right)={x}^{2}[/latex]

[latex]x=\sqrt{\left(6.3\times {10}^{-9}\right)}=\text{7.9}\times {10}^{-5}[/latex]

Therefore, the molar solubility of [latex]\ce{CuBr}[/latex] is 7.9 × 10–5M.

Check Your Learning

Example 16.1.4: Determination of Molar Solubility from Ksp, Part II

The Ksp of calcium hydroxide, [latex]\ce{Ca(OH)2}[/latex], is 1.3 × 10–6. Calculate the molar solubility of calcium hydroxide.

Show Solution

The dissolution equation and solubility product expression are

[latex]{\text{Ca(OH)}}_{2}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{2OH}}^{-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

[latex]{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Ca}^{2+}\right]\left[\text{OH}^{-}\right]^{2}[/latex]

Create an ICE table, leaving the [latex]\ce{Ca(OH)2}[/latex] column empty as it is a solid and does not contribute to the Ksp:

At equilibrium:

[latex]{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Ca}^{2+}\right]\left[\text{OH}^{-}\right]^{2}[/latex]

[latex]1.3\times{10}^{-6}=\left(x\right)\left(2x\right)^{2}=\left(x\right)\left(4x^{2}\right)=4{x}^{3}[/latex]

[latex]x=\sqrt[3]{\dfrac{1.3\times {10}^{-6}}{4}}=\text{6.9}\times {10}^{-3}[/latex]

Therefore, the molar solubility of [latex]\ce{Ca(OH)2}[/latex] is 6.9 × 10–3M.

Check Your Learning

Note that solubility is not always given as a molar value. When the solubility of a compound is given in some unit other than moles per liter, we must convert the solubility into moles per liter (i.e., molarity) in order to use it in the solubility product constant expression. Example 16.1.5 shows how to perform those unit conversions before determining the solubility product equilibrium.

Example 16.1.5: Determination of Ksp from Gram Solubility

Many of the pigments used by artists in oil-based paints (Figure 16.1.2) are sparingly soluble in water. For example, the solubility of the artist’s pigment chrome yellow, [latex]\ce{PbCrO4}[/latex], is 4.6 × 10–6 g/L. Determine the solubility product for [latex]\ce{PbCrO4}[/latex].

Show Solution

We are given the solubility of [latex]\ce{PbCrO4}[/latex] in grams per liter. If we convert this solubility into moles per liter, we can find the equilibrium concentrations of Pb2+ and [latex]{\text{CrO}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex], then Ksp:![This figure shows four horizontally oriented rectangles. The first three from the left are shaded green and the last one at the right is shaded white. Right pointing arrows between the rectangles are labeled “1,” “2,” and “3” moving left to right across the diagram. The first rectangle is labeled “Solubility of P b C r O subscript 4, in g divdided by L.” The second rectangle is labeled “[ P b C r O subscript 4 ], in m o l divided by L.” The third is labeled “[ P b superscript 2 plus] and [ C r O subscript 4 superscript 2 negative ].” The fourth rectangle is labeled “K subscript s p.”](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/courses-images-archive-read-only/wp-content/uploads/sites/887/2015/05/23213942/CNX_Chem_15_01_PbCrO4_img.jpg) Step 1. Use the molar mass of [latex]\ce{PbCrO4}[/latex], [latex]\left(\dfrac{323.2\text{g}}{1\text{mol}}\right)[/latex], to convert the solubility of PbCrO4 in grams per liter into moles per liter:

Step 1. Use the molar mass of [latex]\ce{PbCrO4}[/latex], [latex]\left(\dfrac{323.2\text{g}}{1\text{mol}}\right)[/latex], to convert the solubility of PbCrO4 in grams per liter into moles per liter:

[latex]\begin{array}{l}{ }\left[{\text{PbCrO}}_{4}\right]&=&\dfrac{4.6\times {10}^{-6}{\text{g PbCrO}}_{4}}{1\text{L}}\times \dfrac{1{\text{mol PbCrO}}_{4}}{323.2{\text{g PbCrO}}_{4}}\\& =&\dfrac{1.4\times {10}^{-8}{\text{mol PbCrO}}_{4}}{1\text{L}}\\& =&\text{}1.4\times {10}^{-8}M\end{array}[/latex]

Step 2. The chemical equation for the dissolution indicates that 1 mol of [latex]\ce{PbCrO4}[/latex] gives 1 mol of [latex]\ce{Pb^2+}[/latex](aq) and 1 mol of [latex]{\text{CrO}}_{4}{}^{\text{2-}}\text{(}aq\text{)}:[/latex]

[latex]{\text{PbCrO}}_{4}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Pb}}^{2+}\left(aq\right)+{\text{CrO}}_{4}{}^{2-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

The dissolution stoichiometry shows a 1:1 relation between the molar amounts of compound and its two ions, and so both [latex]\ce{[Pb^2+]}[/latex] and [latex]\left[{\text{CrO}}_{4}{}^{\text{2-}}\right][/latex] are equal to the molar solubility of [latex]\ce{PbCrO4}[/latex]

[latex]\left[\text{Pb}^{2+}\right]=\left[\text{CrO}_{4}^{2-}\right]=1.4\times{10}^{-8}M[/latex]

Step 3. Solve.

[latex]K_{\text{sp}}= [\text{Pb}^{2+}]\left[{\text{CrO}}_{4}{}^{2-}\right]=(1.4\times{10}^{-8})(1.4\times{10}^{-8}) = 2.0\times{10}^{-16}[/latex]

Check Your Learning

Example 16.1.6: Calculating the Solubility of [latex]\ce{Hg2Cl2}[/latex]

Calomel, [latex]\ce{Hg2Cl2}[/latex], is a compound composed of the diatomic ion of mercury(I), [latex]{\text{Hg}}_{2}{}^{\text{2+}}[/latex], and chloride ions, [latex]\ce{Cl-}[/latex]. Although most mercury compounds are now known to be poisonous, eighteenth-century physicians used calomel as a medication. Their patients rarely suffered any mercury poisoning from the treatments because calomel is quite insoluble:

[latex]{\text{Hg}}_{2}{\text{Cl}}_{2}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Hg}}_{2}{}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{2Cl}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\qquad{K}_{\text{sp}}=\text{1.1}\times {10}^{-18}[/latex]

Calculate the molar solubility of [latex]\ce{Hg2Cl2}[/latex].

Show Solution

The molar solubility of [latex]\ce{Hg2Cl2}[/latex] is equal to the concentration of [latex]{\text{Hg}}_{2}{}^{\text{2+}}[/latex] ions because for each 1 mol of [latex]\ce{Hg2Cl2}[/latex] that dissolves, 1 mol of [latex]{\text{Hg}}_{2}{}^{\text{2+}}[/latex] forms:

- Determine the direction of change. Before any [latex]\ce{Hg2Cl2}[/latex] dissolves, Q is zero, and the reaction will shift to the right to reach equilibrium.

- Determine x and equilibrium concentrations. Concentrations and changes are given in the following ICE table:

- Note that the change in the concentration of [latex]\ce{Cl-}[/latex] (2x) is twice as large as the change in the concentration of [latex]{\text{Hg}}_{2}{}^{\text{2+}}[/latex] (x) because 2 mol of Cl– forms for each 1 mol of [latex]{\text{Hg}}_{2}{}^{\text{2+}}[/latex] that forms. [latex]\ce{Hg2Cl2}[/latex] is a pure solid, so it does not appear in the calculation.

- Solve for x and the equilibrium concentrations. We substitute the equilibrium concentrations into the expression for Ksp and calculate the value of x: [latex]{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Hg}_{2}^{2+}\right]\left[\text{Cl}^{-}\right]^{2}[/latex][latex]1.1\times{10}^{-18}=\left(x\right)\left(2x\right)^{2}[/latex][latex]4{x}^{3}=\text{1.1}\times {10}^{-18}[/latex][latex]x=\sqrt[3]{\left(\frac{1.1\times {10}^{-18}}{4}\right)}=\text{6.5}\times {10}^{-7}\text{}M[/latex][latex]\left[{\text{Hg}}_{2}{}^{\text{2+}}\right]=\text{6.5}\times {10}^{-7}\text{}M=\text{6.5}\times {10}^{-7}\text{}M[/latex][latex]\left[\text{Cl}^{-}\right]=2x=2\left(6.5\times{10}^{-7}\right)=1.3\times {10}^{-6}M[/latex]The molar solubility of [latex]\ce{Hg2Cl2}[/latex] is equal to [latex]{\text{[Hg}}_{2}{}^{\text{2+}}][/latex], or 6.5 × 10–7M.

- Check the work. At equilibrium, Q = Ksp:

[latex]Q=\left[\text{Hg}_{2}^{2+}\right]\left[\text{Cl}^{-}\right]^{2}=\left(6.5\times{10}^{-7}\right)\left(1.3\times{10}^{-6}\right)^{2}=1.1\times{10}^{-18}[/latex]

The calculations check.

Check Your Learning

Tabulated Ksp values can also be compared to reaction quotients calculated from experimental data to tell whether a solid will precipitate in a reaction under specific conditions: Q equals Ksp at equilibrium; if Q is less than Ksp, the solid will dissolve until Q equals Ksp; if Q is greater than Ksp, precipitation will occur at a given temperature until Q equals Ksp.

Predicting Precipitation

The equation that describes the equilibrium between solid calcium carbonate and its solvated ions is:

[latex]{\text{CaCO}}_{3}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{CO}}_{3}^{2-}\left(aq\right)\qquad{K}_{sp} = [\text{Ca}^{2+}][\text{CO}_3^{2-}] = 8.7 \times{10}^{-9}[/latex]

It is important to realize that this equilibrium is established in any aqueous solution containing [latex]\ce{Ca^2+}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{CO3^2-}[/latex] ions, not just in a solution formed by saturating water with calcium carbonate. Consider, for example, mixing aqueous solutions of the soluble compounds sodium carbonate and calcium nitrate. If the concentrations of calcium and carbonate ions in the mixture do not yield a reaction quotient, Qsp, that exceeds the solubility product, Ksp, then no precipitation will occur. If the ion concentrations yield a reaction quotient greater than the solubility product, then precipitation will occur, lowering those concentrations until equilibrium is established (Qsp = Ksp). The comparison of Qsp to Ksp to predict precipitation is an example of the general approach to predicting the direction of a reaction first introduced in the chapter on equilibrium. For the specific case of solubility equilibria:

Qsp < Ksp: the reaction proceeds in the forward direction (solution is not saturated; no precipitation observed)

Qsp > Ksp: the reaction proceeds in the reverse direction (solution is supersaturated; precipitation will occur)

This predictive strategy and related calculations are demonstrated in the next few example exercises.

Example 16.1.7: Precipitation of [latex]\ce{Mg(OH)2}[/latex]

The first step in the preparation of magnesium metal is the precipitation of [latex]\ce{Mg(OH)2}[/latex] from sea water by the addition of lime, [latex]\ce{Ca(OH)2}[/latex], a readily available inexpensive source of [latex]\ce{OH-}[/latex] ion:

[latex]{\text{Mg(OH)}}_{2}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Mg}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{2OH}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{K}_{\text{sp}}=\text{2.1}\times {10}^{-13}[/latex]

The concentration of Mg2+(aq) in sea water is 0.0537 M. Will Mg(OH)2 precipitate when enough [latex]\ce{Ca(OH)2}[/latex] is added to give a [latex]\ce{[OH-]}[/latex] of 0.0010 M?

Show Solution

This problem asks whether the reaction:

[latex]{\text{Mg(OH)}}_{2}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Mg}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{2OH}}^{-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

shifts to the left and forms solid [latex]\ce{Mg(OH)2}[/latex] when [latex]\ce{[Mg^2+]}[/latex] = 0.0537 M and [latex]\ce{[OH-]}[/latex] = 0.0010 M. The reaction shifts to the left if Q is greater than Ksp. Calculation of the reaction quotient under these conditions is shown here:

[latex]Q=\left[\text{Mg}^{2+}\right]\left[\text{OH}^{-}\right]^{2}=\left(0.0537\right)\left(0.0010\right)^{2}=5.4\times{10}^{-8}[/latex]

Because Q is greater than Ksp (Q = 5.4 × 10–8 is larger than Ksp = 2.1 × 10–13), we can expect the reaction to shift to the left and form solid magnesium hydroxide. [latex]\ce{Mg(OH)2}[/latex](s) forms until the concentrations of magnesium ion and hydroxide ion are reduced sufficiently so that the value of Q is equal to Ksp.

Check Your Learning

Example 16.1.8: Precipitation of AgCl upon Mixing Solutions

Does silver chloride precipitate when equal volumes of a 2.0 × 10–4–M solution of [latex]\ce{AgNO3}[/latex] and a 2.0 × 10–4–M solution of [latex]\ce{NaCl}[/latex] are mixed?

(Note: The solution also contains Na+ and [latex]{\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}[/latex] ions, but when referring to solubility rules, one can see that sodium nitrate is very soluble and cannot form a precipitate.)

Show Solution

The equation for the equilibrium between solid silver chloride, silver ion, and chloride ion is:

[latex]\text{AgCl}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{Cl}}^{-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

The solubility product is 1.6 × 10–10 (see Solubility Products).

[latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex] will precipitate if the reaction quotient calculated from the concentrations in the mixture of [latex]\ce{AgNO3}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{NaCl}[/latex] is greater than Ksp. The volume doubles when we mix equal volumes of [latex]\ce{AgNO3}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{NaCl}[/latex] solutions, so each concentration is reduced to half its initial value. Consequently, immediately upon mixing, [latex]\ce{[Ag+]}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{[Cl-]}[/latex] are both equal to:

[latex]\frac{1}{2}\left(2.0\times {10}^{-4}\right)\text{}M=\text{1.0}\times {10}^{-4}\text{}M[/latex].

The reaction quotient, Q, is momentarily greater than Ksp for [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex], so a supersaturated solution is formed:

[latex]Q=\left[\text{Ag}^{+}\right]\left[\text{Cl}^{-}\right]=\left(1.0\times{10}^{-4}\right)\left(1.0\times {10}^{-4}\right)=1.0\times{10}^{-8}\gt{K}_{\text{sp}}[/latex]

Since supersaturated solutions are unstable, [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex] will precipitate from the mixture until the solution returns to equilibrium, with Q equal to Ksp.

Check Your Learning

In the previous two examples, we have seen that Mg(OH)2 or [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex] precipitate when Q is greater than Ksp. In general, when a solution of a soluble salt of the Mm+ ion is mixed with a solution of a soluble salt of the Xn– ion, the solid, MpXq precipitates if the value of Q for the mixture of Mm+ and Xn– is greater than Ksp for MpXq. Thus, if we know the concentration of one of the ions of a slightly soluble ionic solid and the value for the solubility product of the solid, then we can calculate the concentration that the other ion must exceed for precipitation to begin. To simplify the calculation, we will assume that precipitation begins when the reaction quotient becomes equal to the solubility product constant.

Example 16.1.9: Precipitation of Calcium Oxalate

Blood will not clot if calcium ions are removed from its plasma. Some blood collection tubes contain salts of the oxalate ion, [latex]{\text{C}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex], for this purpose (Figure 16.1.4). At sufficiently high concentrations, the calcium and oxalate ions form solid, [latex]\ce{CaC2O2·H2O}[/latex] (which also contains water bound in the solid). The concentration of [latex]\ce{Ca^2+}[/latex] in a sample of blood serum is 2.2 × 10–3M. What concentration of [latex]{\text{C}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex] ion must be established before [latex]\ce{CaC2O4·H2O}[/latex] begins to precipitate?

Show Solution

The equilibrium expression is:

[latex]{\text{CaC}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{C}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}{}^{2-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

For this reaction:

[latex]{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[{\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\right]\left[{\text{C}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}^{2-}\right]=1.96\times {10}^{-8}[/latex] (see Solubility Products)

[latex]\ce{CaC2O4}[/latex] does not appear in this expression because it is a solid. Water does not appear because it is the solvent.

Solid [latex]\ce{CaC2O4}[/latex] does not begin to form until Q equals Ksp. Because we know Ksp and [latex]\ce{[Ca^2+]}[/latex], we can solve for the concentration of [latex]{\text{C}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex] that is necessary to produce the first trace of solid:

[latex]Q={K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Ca}^{2+}\right]\left[\text{C}_{2}\text{O}_{4}^{2-}\right]=1.96\times{10}^{-8}[/latex]

[latex]\left(2.2\times {10}^{-3}\right){\text{[C}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}{}^{\text{2-}}]=\text{1.96}\times {10}^{-8}[/latex]

[latex]\left[{\text{C}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}{}^{2-}\right]=\dfrac{1.96\times {10}^{-8}}{2.2\times {10}^{-3}}=8.9\times {10}^{-6}[/latex]

A concentration of [latex]\left[{\text{C}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex] = 8.9 × 10–6M is necessary to initiate the precipitation of CaC2O4 under these conditions.

Check Your Learning

It is sometimes useful to know the concentration of an ion that remains in solution after precipitation. We can use the solubility product for this calculation too: If we know the value of Ksp and the concentration of one ion in solution, we can calculate the concentration of the second ion remaining in solution. The calculation is of the same type as that in Example 16.1.9—calculation of the concentration of a species in an equilibrium mixture from the concentrations of the other species and the equilibrium constant. However, the concentrations are different; we are calculating concentrations after precipitation is complete, rather than at the start of precipitation.

Example 16.1.10: Concentrations Following Precipitation

Clothing washed in water that has a manganese [[latex]\ce{Mn^2+}[/latex](aq)] concentration exceeding 0.1 mg/L (1.8 × 10–6M) may be stained by the manganese upon oxidation, but the amount of Mn2+ in the water can be reduced by adding a base. If a person doing laundry wishes to add a buffer to keep the pH high enough to precipitate the manganese as the hydroxide, [latex]\ce{Mn(OH)2}[/latex], what pH is required to keep [latex]\ce{[Mn^2+]}[/latex] equal to 1.8 × 10–6M?

Show Solution

The dissolution of [latex]\ce{Mn(OH)2}[/latex] is described by the equation:

[latex]{\text{Mn(OH)}}_{2}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Mn}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{2OH}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{K}_{\text{sp}}=\text{2}\times {10}^{-13}[/latex]

We need to calculate the concentration of [latex]\ce{OH-}[/latex] when the concentration of [latex]\ce{Mn^2+}[/latex] is 1.8 × 10–6M. From that, we calculate the pH. At equilibrium:

[latex]{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Mn}^{2+}\right]\left[\text{OH}^{-}\right]^{2}\qquad\text{ or }\qquad\left(1.8\times {10}^{-6}\right){\left[{\text{OH}}^{-}\right]}^{2}=\text{2}\times {10}^{-13}[/latex]

so

[latex]\left[{\text{OH}}^{-}\right]=\text{3.3}\times {10}^{-4}M[/latex].

Now we calculate the pH from the pOH:

[latex]\begin{array}{c}\text{pOH}=-\text{log}\left[{\text{OH}}^{-}\right]=-\text{log}\left(3.3\times {10}^{- 4}\right)=\text{3.48}\\ \text{pH}=\text{14.00}-\text{pOH}=\text{14.00}-\text{3.48}=\text{10.52}\end{array}[/latex]

(final result rounded to one significant digit, limited by the certainty of the Ksp)

Check Your Learning

In solutions containing two or more ions that may form insoluble compounds with the same counter ion, an experimental strategy called selective precipitation may be used to remove individual ions from solution. By increasing the counter ion concentration in a controlled manner, ions in solution may be precipitated individually, assuming their compound solubilities are adequately different. In solutions with equal concentrations of target ions, the ion forming the least soluble compound will precipitate first (at the lowest concentration of counter ion), with the other ions subsequently precipitating as their compound’s solubilities are reached. As an illustration of this technique, the next example exercise describes separation of a two halide ions via precipitation of one as a silver salt.

Example 16.1.11: Precipitation of Silver Halides

A solution contains 0.00010 mol of [latex]\ce{KBr}[/latex] and 0.10 mol of [latex]\ce{KCl}[/latex] per liter. [latex]\ce{AgNO3}[/latex] is gradually added to this solution. Which forms first, solid [latex]\ce{AgBr}[/latex] or solid [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex]?

Show Solution

The two equilibria involved are:

[latex]\text{AgCl}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{Cl}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{K}_{\text{sp}}=\text{1.6}\times {10}^{-10}[/latex]

[latex]\text{AgBr}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{Br}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,K_{\text{sp}}=\text{5.0}\times {10}^{-13}[/latex]

If the solution contained about equal concentrations of [latex]\ce{Cl-}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{Br-}[/latex], then the silver salt with the smallest Ksp ([latex]\ce{AgBr}[/latex]) would precipitate first. The concentrations are not equal, however, so we should find the [latex]\ce{[Ag+]}[/latex] at which [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex] begins to precipitate and the [latex]\ce{[Ag+]}[/latex] at which [latex]\ce{AgBr}[/latex] begins to precipitate. The salt that forms at the lower [latex]\ce{[Ag+]}[/latex] precipitates first.

[latex]\ce{AgBr}[/latex] precipitates when Q equals Ksp for [latex]\ce{AgBr}[/latex]

[latex]Q=K_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Ag}^{+}\right]\left[\text{Br}^{-}\right]=\left[\text{Ag}^{+}\right]\left(0.00010\right)=5.0\times {10}^{-13}[/latex]

[latex][{\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\text{]}=\dfrac{\text{5.0}\times {10}^{-13}}{0.00010}=\text{5.0}\times {10}^{-9}[/latex]

[latex]\ce{AgBr}[/latex] begins to precipitate when [Ag+] is 5.0 × 10–9M.

For [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex]: [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex] precipitates when Q equals Ksp for [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex] (1.6 × 10–10). When [latex]\ce{[Cl-]}[/latex] = 0.10 M:

[latex]{Q}_{\text{sp}}=K_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Ag}^{+}\right]\left[\text{Cl}^{-}\right]=\left[\text{Ag}^{+}\right]\left(0.10\right)=1.6\times{10}^{-10}[/latex]

[latex][{\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\text{]}=\dfrac{1.6\times {10}^{-10}}{0.10}\text{=1.6}\times {10}^{-9}M[/latex]

[latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex] begins to precipitate when [latex]\ce{[Ag+]}[/latex] is 1.6 × 10–9M.

[latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex] begins to precipitate at a lower [latex]\ce{[Ag+]}[/latex] than [latex]\ce{AgBr}[/latex], so [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex] begins to precipitate first. Note the chloride ion concentration of the initial mixture was significantly greater than the bromide ion concentration, and so silver chloride precipitated first despite having a Ksp greater than that of silver bromide.

Check Your Learning

Common Ion Effect

Compared with pure water, the solubility of an ionic compound is less in aqueous solutions containing a common ion (one also produced by dissolution of the ionic compound). This is an example of a phenomenon known as the common ion effect, which is a consequence of the law of mass action that may be explained using Le ChÂtelier’s principle. Consider the dissolution of silver iodide:

[latex]\text{AgI}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{I}}^{-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

This solubility equilibrium may be shifted left by the addition of either silver(I) or iodide ions, resulting in the precipitation of AgI and lowered concentrations of dissolved [latex]\ce{Ag+}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{I-}[/latex]. In solutions that already contain either of these ions, less [latex]\ce{AgI}[/latex] may be dissolved than in solutions without these ions.

This effect may also be explained in terms of mass action as represented in the solubility product expression:

[latex]K_{sp} = [\text{Ag}^+][\text{I}^-][/latex]

The mathematical product of silver(I) and iodide ion molarities is constant in an equilibrium mixture regardless of the source of the ions, and so an increase in one ion’s concentration must be balanced by a proportional decrease in the other.

Example 16.1.12: Common Ion Effect on Solubility

What is the effect on the amount of solid [latex]\ce{Mg(OH)2}[/latex] and the concentrations of [latex]\ce{Mg^2+}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{OH-}[/latex] when each of the following are added to a saturated solution of [latex]\ce{Mg(OH)2}[/latex]?

- [latex]\ce{MgCl2}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{KOH}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{NaNO3}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Mg(OH)2}[/latex]

Show Solution

The solubility equilibrium is

[latex]\text{Mg(OH)}_2(s) \rightleftharpoons \text{Mg}^{2+} (aq) + 2\text{OH}^- (aq)[/latex]

- Adding a common ion, [latex]\ce{Mg^2+}[/latex], will increase the concentration of this ion and shift the solubility equilibrium to the left, decreasing the concentration of hydroxide ion and increasing the amount of undissolved magnesium hydroxide.

- Adding a common ion, [latex]\ce{OH-}[/latex], will increase the concentration of this ion and shift the solubility equilibrium to the left, decreasing the concentration of magnesium ion and increasing the amount of undissolved magnesium hydroxide.

- The added compound does not contain a common ion, and no effect on the magnesium hydroxide solubility equilibrium is expected.

- Adding more solid magnesium hydroxide will increase the amount of undissolved compound in the mixture. The solution is already saturated, though, so the concentrations of dissolved magnesium and hydroxide ions will remain the same.

- [latex]Q = [\text{Mg}^{2+}][\text{OH}^-]^2[/latex]

- Thus, changing the amount of solid magnesium hydroxide in the mixture has no effect on the value of Q, and no shift is required to restore Q to the value of the equilibrium constant.

Check Your Learning

Key Concepts and Summary

The equilibrium constant for an equilibrium involving the precipitation or dissolution of a slightly soluble ionic solid is called the solubility product, Ksp, of the solid. When we have a heterogeneous equilibrium involving the slightly soluble solid MpXq and its ions Mm+ and Xn–:

[latex]\text{M}_{\text{p}}{\text{X}}_{\text{q}}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons p{\text{M}}^{\text{m+}}\left(aq\right)+q{\text{X}}^{\text{n}-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

We write the solubility product expression as:

[latex]{K}_{\text{sp}}={{\text{[M}}^{\text{m+}}\text{]}}^{\text{p}}{{\text{[X}}^{\text{n}-}]}^{\text{q}}[/latex]

The solubility product of a slightly soluble electrolyte can be calculated from its solubility; conversely, its solubility can be calculated from its Ksp, provided the only significant reaction that occurs when the solid dissolves is the formation of its ions.

A slightly soluble electrolyte begins to precipitate when the magnitude of the reaction quotient for the dissolution reaction exceeds the magnitude of the solubility product. Precipitation continues until the reaction quotient equals the solubility product.

Key Equations

- [latex]\text{Mp}_{\text{Xq}}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons p{\text{M}}^{\text{m+}}\left(aq\right)+q{\text{X}}^{\text{n}-}\left(aq\right)\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{M}^{\text{m+}}\right]^{\text{p}}\left[\text{X}^{\text{n}-}\right]^\text{q}[/latex]

Try It

- Complete the changes in concentrations for each of the following reactions:

- [latex]\begin{array}{ccc}\text{AgI}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow & {\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)& +{\text{I}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\\ & x&\text{ _____}\end{array}[/latex]

- [latex]\begin{array}{ccc}{\text{CaCO}}_{3}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow & {\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+& {\text{CO}}_{3}{}^{2-}\left(aq\right)\\ & \text{____}& x\end{array}[/latex]

- [latex]\begin{array}{ccc}\text{Mg}{\left(\text{OH}\right)}_{2}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow & {\text{Mg}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+& 2{\text{OH}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\\ & x&\text{ _____}\end{array}[/latex]

- [latex]\begin{array}{ccc}{\text{Mg}}_{3}{\left({\text{PO}}_{4}\right)}_{2}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow & 3{\text{Mg}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+& 2{\text{PO}}_{4}{}^{3-}\left(aq\right)\\ & & x\text{_____}\end{array}[/latex]

- [latex]\begin{array}{cccc}{\text{Ca}}_{5}{\left({\text{PO}}_{4}\right)}_{3}\text{OH}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow & 5{\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+& 3{\text{PO}}_{4}^{3-}\left(aq\right)+& {\text{OH}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\\ & \text{_____}& \text{_____}& x\end{array}[/latex]

- Complete the changes in concentrations for each of the following reactions:

- [latex]\begin{array}{ccc}{\text{BaSO}}_{4}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow & {\text{Ba}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+& {\text{SO}}_{4}{}^{2-}\left(aq\right)\\ & x& \text{_____}\end{array}[/latex]

- [latex]\begin{array}{ccc}{\text{Ag}}_{2}{\text{SO}}_{4}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow & 2{\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+& {\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}\left(aq\right)\\ & \text{_____}& x\end{array}[/latex]

- [latex]\begin{array}{ccc}\text{Al}{\left(\text{OH}\right)}_{3}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow & {\text{Al}}^{\text{3+}}\left(aq\right)+& 3{\text{OH}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\\ & x& \text{_____}\end{array}[/latex]

- [latex]\begin{array}{cccc}\text{Pb}\left(\text{OH}\right)\text{Cl}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow & {\text{Pb}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+& {\text{OH}}^{-}\left(aq\right)+& {\text{Cl}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\\ & \text{_____}\text{}& x& \text{_____}\end{array}[/latex]

- [latex]\begin{array}{ccc}{\text{Ca}}_{3}{\left({\text{AsO}}_{4}\right)}_{2}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow & 3{\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+& 2{\text{AsO}}_{4}^{3-}\left(aq\right)\\ & 3x& \text{_____}\end{array}[/latex]

- How do the concentrations of [latex]\ce{Ag+}[/latex] and [latex]{\text{CrO}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex] in a saturated solution above 1.0 g of solid [latex]\ce{Ag2CrO4}[/latex] change when 100 g of solid [latex]\ce{Ag2CrO4}[/latex] is added to the system? Explain.

- How do the concentrations of [latex]\ce{Pb^2+}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{S2-}[/latex] change when [latex]\ce{K2S}[/latex] is added to a saturated solution of [latex]\ce{PbS}[/latex]?

- What additional information do we need to answer the following question: How is the equilibrium of solid silver bromide with a saturated solution of its ions affected when the temperature is raised?

- Which of the following slightly soluble compounds has a solubility greater than that calculated from its solubility product because of hydrolysis of the anion present: [latex]\ce{CoSO3}[/latex], [latex]\ce{CuI}[/latex], [latex]\ce{PbCO3}[/latex], [latex]\ce{PbCl2}[/latex], [latex]\ce{Tl2S}[/latex], [latex]\ce{KClO4}[/latex]?

- Which of the following slightly soluble compounds has a solubility greater than that calculated from its solubility product because of hydrolysis of the anion present: [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex], [latex]\ce{BaSO4}[/latex], [latex]\ce{CaF2}[/latex], [latex]\ce{Hg2I2}[/latex], [latex]\ce{MnCO3}[/latex], [latex]\ce{ZnS}[/latex], [latex]\ce{PbS}[/latex]?

- Write the ionic equation for dissolution and the solubility product (Ksp) expression for each of the following slightly soluble ionic compounds:

- [latex]\ce{PbCl2}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Ag2S}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Sr3(PO4)2}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{SrSO4}[/latex]

- Write the ionic equation for the dissolution and the Ksp expression for each of the following slightly soluble ionic compounds:

- [latex]\ce{LaF3}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{CaCO3}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Ag2SO4}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Pb(OH)2}[/latex]

- The Handbook of Chemistry and Physics gives solubilities of the following compounds in grams per 100 mL of water. Because these compounds are only slightly soluble, assume that the volume does not change on dissolution and calculate the solubility product for each.

- [latex]\ce{BaSiF6}[/latex], 0.026 g/100 mL (contains [latex]{\text{SiF}}_{6}^{2-}[/latex] ions)

- [latex]\ce{Ce(IO3)4}[/latex], 1.5 × 10–2 g/100 mL

- [latex]\ce{Gd2(SO4)3}[/latex], 3.98 g/100 mL

- [latex]\ce{(NH4)2PtBr6}[/latex], 0.59 g/100 mL (contains [latex]{\text{PtBr}}_{6}^{2-}[/latex] ions)

- The Handbook of Chemistry and Physics gives solubilities of the following compounds in grams per 100 mL of water. Because these compounds are only slightly soluble, assume that the volume does not change on dissolution and calculate the solubility product for each.

- [latex]\ce{BaSeO4}[/latex], 0.0118 g/100 mL

- [latex]\ce{Ba(BrO3)2·H2O}[/latex], 0.30 g/100 mL

- [latex]\ce{NH4MgAsO4·6H2O}[/latex], 0.038 g/100 mL

- [latex]\ce{La2(MoO4)2}[/latex], 0.00179 g/100 mL

- Use solubility products and predict which of the following salts is the most soluble, in terms of moles per liter, in pure water: [latex]\ce{CaF2}[/latex], [latex]\ce{Hg2Cl2}[/latex], [latex]\ce{PbI2}[/latex], or [latex]\ce{Sn(OH)2}[/latex].

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the molar solubility of each of the following from its solubility product:

- [latex]\ce{KHC4H4O6}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{PbI2}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Ag4[Fe(CN)6]}[/latex], a salt containing the [latex]{\text{Fe(CN)}}_{4}^{-}[/latex] ion.

- [latex]\ce{Hg2I2}[/latex]

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the molar solubility of each of the following from its solubility product:

- [latex]\ce{Ag2SO4}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{PbBr2}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{AgI}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{CaC2O4·H2O}[/latex]

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the concentration of all solute species in each of the following solutions of salts in contact with a solution containing a common ion. Show that changes in the initial concentrations of the common ions can be neglected.

- [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex](s) in 0.025 M NaCl

- [latex]\ce{CaF2}[/latex](s) in 0.00133 M KF

- [latex]\ce{Ag2SO4}[/latex](s) in 0.500 L of a solution containing 19.50 g of [latex]\ce{K2SO4}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Zn(OH)2}[/latex](s) in a solution buffered at a pH of 11.45

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the concentration of all solute species in each of the following solutions of salts in contact with a solution containing a common ion. Show that changes in the initial concentrations of the common ions can be neglected.

- [latex]\ce{TlCl}[/latex](s) in 1.250 M [latex]\ce{HCl}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{PbI2}[/latex](s) in 0.0355 M [latex]\ce{CaI2}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Ag2CrO4}[/latex](s) in 0.225 L of a solution containing 0.856 g of [latex]\ce{K2CrO4}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Cd(OH)2}[/latex](s) in a solution buffered at a pH of 10.995

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the concentration of all solute species in each of the following solutions of salts in contact with a solution containing a common ion. Show that it is not appropriate to neglect the changes in the initial concentrations of the common ions.

- [latex]\ce{TlCl}[/latex](s) in 0.025 M [latex]\ce{TlNO3}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{BaF2}[/latex](s) in 0.0313 M [latex]\ce{KF}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{MgC2O4}[/latex] in 2.250 L of a solution containing 8.156 g of [latex]\ce{Mg(NO3)2}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Ca(OH)2}[/latex](s) in an unbuffered solution initially with a pH of 12.700

- Explain why the changes in concentrations of the common ions in Question 17 can be neglected.

- Explain why the changes in concentrations of the common ions in Question 18 cannot be neglected.

- Calculate the solubility of aluminum hydroxide, [latex]\ce{Al(OH)3}[/latex], in a solution buffered at pH 11.00.

- Refer to Solubility Products for solubility products for calcium salts. Determine which of the calcium salts listed is most soluble in moles per liter and which is most soluble in grams per liter.

- Most barium compounds are very poisonous; however, barium sulfate is often administered internally as an aid in the X-ray examination of the lower intestinal tract (Figure 16.1.3). This use of BaSO4 is possible because of its low solubility. Calculate the molar solubility of [latex]\ce{BaSO4}[/latex] and the mass of barium present in 1.00 L of water saturated with [latex]\ce{BaSO4}[/latex].

- Public Health Service standards for drinking water set a maximum of 250 mg/L (2.60 × 10–3 M) of [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex] because of its cathartic action (it is a laxative). Does natural water that is saturated with CaSO4 (“gyp” water) as a result or passing through soil containing gypsum, [latex]\ce{CaSO4}\cdot \ce{2H2O}[/latex], meet these standards? What is [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex] in such water?

- Perform the following calculations:

- Calculate [latex]\ce{[Ag+]}[/latex] in a saturated aqueous solution of [latex]\ce{AgBr}[/latex].

- What will [latex]\ce{[Ag+]}[/latex] be when enough [latex]\ce{KBr}[/latex] has been added to make [latex]\ce{[Br-]}[/latex] = 0.050 M?

- What will [latex]\ce{[Br-]}[/latex] be when enough [latex]\ce{AgNO3}[/latex] has been added to make [latex]\ce{[Ag+]}[/latex] = 0.020 M?

- The solubility product of [latex]\ce{CaSO4·2H2O}[/latex] is 2.4 × 10–5. What mass of this salt will dissolve in 1.0 L of 0.010 M [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}?[/latex]

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the concentrations of ions in a saturated solution of each of the following (see Solubility Products).

- [latex]\ce{TlCl}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{BaF2}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Ag2CrO4}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{CaC2O4·H2O}[/latex]

- the mineral anglesite, [latex]\ce{PbSO4}[/latex]

- Assuming that no equilibria other than dissolution are involved, calculate the concentrations of ions in a saturated solution of each of the following (see Solubility Products):

- [latex]\ce{AgI}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Ag2SO4}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Mn(OH)2}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Sr(OH)2·8H2O}[/latex]

- the mineral brucite, [latex]\ce{Mg(OH)2}[/latex]

- The following concentrations are found in mixtures of ions in equilibrium with slightly soluble solids. From the concentrations given, calculate Ksp for each of the slightly soluble solids indicated:

- [latex]\ce{AgBr: [Ag+]}[/latex] = 5.7 × 10–7M, [Br–] = 5.7 × 10–7M

- [latex]\ce{CaCO3: [Ca^2+]}[/latex] = 5.3 × 10–3M, [latex]\left[\text{CO}_{3}^{2-}\right][/latex] = 9.0 × 10–7M

- [latex]\ce{PbF2: [Pb^2+]}[/latex] = 2.1 × 10–3M, [F–] = 4.2 × 10–3M

- [latex]\ce{Ag2CrO4: [Ag+]}[/latex] = 5.3 × 10–5M, 3.2 × 10–3M

- [latex]\ce{InF3: [In^3+]}[/latex] = 2.3 × 10–3M, [F–] = 7.0 × 10–3M

- The following concentrations are found in mixtures of ions in equilibrium with slightly soluble solids. From the concentrations given, calculate Ksp for each of the slightly soluble solids indicated:

- [latex]\ce{TlCl: [Tl+]}[/latex] = 1.21 × 10–2M, [Cl–] = 1.2 × 10–2M

- [latex]\ce{Ce(IO3)4: [Ce^4+]}[/latex] = 1.8 × 10–4M, [latex]\left[\text{IO}_{3}^{-}\right][/latex] = 2.6 × 10–13M

- [latex]\ce{Gd2(SO4)3: [Gd^3+]}[/latex] = 0.132 M, [latex]\left[\text{SO}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex] = 0.198 M

- [latex]\ce{Ag2SO4: [Ag+]}[/latex] = 2.40 × 10–2M, [latex]\left[{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex] = 2.05 × 10–2M

- [latex]\ce{BaSO4: [Ba^2+]}[/latex] = 0.500 M, [latex]\left[{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex] = 2.16 × 10–10M

- Which of the following compounds precipitates from a solution that has the concentrations indicated? (See Solubility Products for Ksp values.)

- [latex]\ce{KClO4: [K+]}[/latex] = 0.01 M, [latex]\left[{\text{ClO}}_{4}^{-}\right][/latex] = 0.01 M

- [latex]\ce{K2PtCl6: [K+]}[/latex] = 0.01 M, [latex]{\text{[PtCl}}_{6}^{2-}][/latex] = 0.01 M

- [latex]\ce{PbI2: [Pb^2+]}[/latex] = 0.003 M, [I–] = 1.3 × 10–3M

- [latex]\ce{Ag2S: [Ag+]}[/latex] = 1 × 10–10M, [S2–] = 1 × 10–13M

- Which of the following compounds precipitates from a solution that has the concentrations indicated? (See Solubility Products for Ksp values.)

- [latex]\ce{CaCO3: [Ca^2+]}[/latex] = 0.003 M, [latex]{\text{[CO}}_{3}^{2-}][/latex] = 0.003 M

- [latex]\ce{Co(OH)2: [Co^2+]}[/latex] = 0.01 M, [OH–] = 1 × 10–7M

- [latex]\ce{CaHPO4: [Ca^2+]}[/latex] = 0.01 M, [latex]{\text{[HPO}}_{4}^{2-}][/latex] = 2 × 10–6M

- [latex]\ce{Pb3(PO4)2: [Pb^2+]}[/latex] = 0.01 M, [latex]{\text{[PO}}_{4}^{3-}][/latex] 1 × 10–13M

- Calculate the concentration of [latex]\ce{Tl+}[/latex] when [latex]\ce{TlCl}[/latex] just begins to precipitate from a solution that is 0.0250 M in [latex]\ce{Cl-}[/latex].

- Calculate the concentration of sulfate ion when [latex]\ce{BaSO4}[/latex] just begins to precipitate from a solution that is 0.0758 M in [latex]\ce{Ba^2+}[/latex].

- Calculate the concentration of [latex]\ce{Sr^2+}[/latex] when [latex]\ce{SrF2}[/latex] starts to precipitate from a solution that is 0.0025 M in [latex]\ce{F-}[/latex].

- Calculate the concentration of [latex]{\text{PO}}_{4}^{3-}[/latex] when [latex]\ce{Ag3PO4}[/latex] starts to precipitate from a solution that is 0.0125 M in [latex]\ce{Ag+}[/latex].

- Calculate the concentration of [latex]\ce{F-}[/latex] required to begin precipitation of [latex]\ce{CaF2}[/latex] in a solution that is 0.010 M in [latex]\ce{Ca^2+}[/latex].

- Calculate the concentration of [latex]\ce{Ag+}[/latex] required to begin precipitation of [latex]\ce{Ag2CO3}[/latex] in a solution that is 2.50 × 10–6M in [latex]{\text{CO}}_{3}^{2-}[/latex].

- What [latex]\ce{[Ag+]}[/latex] is required to reduce [latex]\ce{[CO3^2-]}[/latex] to 8.2 × 10–4M by precipitation of [latex]\ce{Ag2CO3}[/latex]?

- What [latex]\ce{[F-]}[/latex] is required to reduce [latex]\ce{[Ca^2+]}[/latex] to 1.0 × 10–4M by precipitation of [latex]\ce{CaF2}[/latex]?

- A volume of 0.800 L of a 2 × 10–4–M [latex]\ce{Ba(NO3)2}[/latex] solution is added to 0.200 L of 5 × 10–4M [latex]\ce{Li2SO4}[/latex]. Does [latex]\ce{BaSO4}[/latex] precipitate? Explain your answer.

- Perform these calculations for nickel(II) carbonate.

- With what volume of water must a precipitate containing [latex]\ce{NiCO3}[/latex] be washed to dissolve 0.100 g of this compound? Assume that the wash water becomes saturated with [latex]\ce{NiCO3}[/latex] (Ksp = 1.36 × 10–7).

- If the [latex]\ce{NiCO3}[/latex] were a contaminant in a sample of CoCO3 (Ksp = 1.0 × 10–12), what mass of [latex]\ce{CoCO3}[/latex] would have been lost? Keep in mind that both [latex]\ce{NiCO3}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{CoCO3}[/latex] dissolve in the same solution.

- Iron concentrations greater than 5.4 × 10–6M in water used for laundry purposes can cause staining. What [latex]\ce{[OH-]}[/latex] is required to reduce [latex]\ce{[Fe^2+]}[/latex] to this level by precipitation of [latex]\ce{Fe(OH)2}[/latex]?

- A solution is 0.010 M in both [latex]\ce{Cu^2+}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{Cd^2+}[/latex]. What percentage of [latex]\ce{Cd^2+}[/latex] remains in the solution when 99.9% of the [latex]\ce{Cu^2+}[/latex] has been precipitated as [latex]\ce{CuS}[/latex] by adding sulfide?

- A solution is 0.15 M in both [latex]\ce{Pb^2+}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{Ag+}[/latex]. If [latex]\ce{Cl-}[/latex] is added to this solution, what is [latex]\ce{[Ag+]}[/latex] when [latex]\ce{PbCl2}[/latex] begins to precipitate?

- What reagent might be used to separate the ions in each of the following mixtures, which are 0.1 M with respect to each ion? In some cases it may be necessary to control the [latex]\ce{pH}[/latex]. (Hint: Consider the Ksp values given in Solubility Products.)

- [latex]{\text{Hg}}_{2}^{2+}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{Cu^2+}[/latex]

- [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{Cl-}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Hg^2+}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{Co^2+}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Zn^2+}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{Sr^2+}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Ba^2+}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{Mg^2+}[/latex]

- [latex]{\text{CO}}_{3}^{2-}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{OH-}[/latex]

- A solution contains 1.0 × 10–5 mol of [latex]\ce{KBr}[/latex] and 0.10 mol of [latex]\ce{KCl}[/latex] per liter. [latex]\ce{AgNO3}[/latex] is gradually added to this solution. Which forms first, solid [latex]\ce{AgBr}[/latex] or solid [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex]?

- A solution contains 1.0 × 10–2 mol of [latex]\ce{KI}[/latex] and 0.10 mol of [latex]\ce{KCl}[/latex] per liter. [latex]\ce{AgNO3}[/latex] is gradually added to this solution. Which forms first, solid AgI or solid [latex]\ce{AgCl}[/latex]?

- The calcium ions in human blood serum are necessary for coagulation (Figure 16.1.4). Potassium oxalate, [latex]\ce{K2C2O4}[/latex], is used as an anticoagulant when a blood sample is drawn for laboratory tests because it removes the calcium as a precipitate of [latex]\ce{CaC2O4·H2O}[/latex]. It is necessary to remove all but 1.0% of the [latex]\ce{Ca^2+}[/latex] in serum in order to prevent coagulation. If normal blood serum with a buffered pH of 7.40 contains 9.5 mg of [latex]\ce{Ca^2+}[/latex] per 100 mL of serum, what mass of [latex]\ce{K2C2O4}[/latex] is required to prevent the coagulation of a 10 mL blood sample that is 55% serum by volume? (All volumes are accurate to two significant figures. Note that the volume of serum in a 10-mL blood sample is 5.5 mL. Assume that the Ksp value for [latex]\ce{CaC2O4}[/latex] in serum is the same as in water.)

- About 50% of urinary calculi (kidney stones) consist of calcium phosphate, [latex]\ce{Ca3(PO4)2}[/latex]. The normal mid range calcium content excreted in the urine is 0.10 g of [latex]\ce{Ca^2+}[/latex] per day. The normal mid range amount of urine passed may be taken as 1.4 L per day. What is the maximum concentration of phosphate ion that urine can contain before a calculus begins to form?

- The pH of normal urine is 6.30, and the total phosphate concentration [latex]\left(\left[\text{PO}_{4}^{3-}\right]+\left[{\text{HPO}}_{4}^{2-}\right]+\left[{\text{H}}_{2}{\text{PO}}_{4}^{-}\right]+\left[\text{H}_3\text{PO}_4\right]\right)[/latex] is 0.020 M. What is the minimum concentration of [latex]\ce{Ca^2+}[/latex] necessary to induce kidney stone formation? (See Question 49 for additional information.)

- Magnesium metal (a component of alloys used in aircraft and a reducing agent used in the production of uranium, titanium, and other active metals) is isolated from sea water by the following sequence of reactions: [latex]{\text{Mg}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{Ca(OH)}}_{2}\left(aq\right)\longrightarrow {\text{Mg(OH)}}_{2}\left(s\right)+{\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)[/latex][latex]{\text{Mg(OH)}}_{2}\left(s\right)+\text{2HCl}(aq)\longrightarrow {\text{MgCl}}_{2}\left(s\right)+{\text{2H}}_{2}\text{O}\left(l\right)[/latex]

[latex]{\text{MgCl}}_{2}\left(l\right)\stackrel{\text{electrolysis}}{\longrightarrow }\text{Mg}\left(s\right)+{\text{Cl}}_{2}\left(g\right)[/latex]Sea water has a density of 1.026 g/cm3 and contains 1272 parts per million of magnesium as [latex]\ce{Mg^2+}[/latex](aq) by mass. What mass, in kilograms, of [latex]\ce{Ca(OH)2}[/latex] is required to precipitate 99.9% of the magnesium in 1.00 × 103 L of sea water? - Hydrogen sulfide is bubbled into a solution that is 0.10 M in both [latex]\ce{Pb^2+}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{Fe^2+}[/latex] and 0.30 M in [latex]\ce{HCl}[/latex]. After the solution has come to equilibrium it is saturated with [latex]\ce{H2S}[/latex] ([latex]\ce{[H2S]}[/latex] = 0.10 M). What concentrations of [latex]\ce{Pb^2+}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{Fe^2+}[/latex] remain in the solution? For a saturated solution of H2S we can use the equilibrium:[latex]{\text{H}}_{2}\text{S}\left(aq\right)+{\text{2H}}_{2}\text{O}\left(l\right)\rightleftharpoons {\text{2H}}_{3}{\text{O}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{S}}^{2-}\left(aq\right)K=1.0\times 1{0}^{-26}[/latex](Hint: The [latex]\left[{\text{H}}_{3}{\text{O}}^{\text{+}}\right][/latex] changes as metal sulfides precipitate.)

- Perform the following calculations involving concentrations of iodate ions:

- The iodate ion concentration of a saturated solution of [latex]\ce{La(IO3)3}[/latex] was found to be 3.1 × 10–3 mol/L. Find the Ksp.

- Find the concentration of iodate ions in a saturated solution of [latex]\ce{Cu(IO3)2}[/latex] (Ksp = 7.4 × 10–8).

- Calculate the molar solubility of [latex]\ce{AgBr}[/latex] in 0.035 M [latex]\ce{NaBr}[/latex] (Ksp = 5 × 10–13).

- How many grams of [latex]\ce{Pb(OH)2}[/latex] will dissolve in 500 mL of a 0.050-M [latex]\ce{PbCl2}[/latex] solution (Ksp = 1.2 × 10–15)?

- Use this simulation to study the process of salts dissolving and forming saturated solutions to complete the following exercise. Using 0.01 g [latex]\ce{CaF2}[/latex], give the Ksp values found in a 0.2-M solution of each of the salts. Discuss why the values change as you change soluble salts.

- How many grams of Milk of Magnesia, [latex]\ce{Mg(OH)2}[/latex] (s) (58.3 g/mol), would be soluble in 200 mL of water. Ksp = 7.1 × 10–12. Include the ionic reaction and the expression for Ksp in your answer. What is the pH? (Kw = 1 × 10–14 = [latex]\left[{\text{H}}_{3}{\text{O}}^{\text{+}}\right][/latex] [latex]\ce{[OH-]}[/latex])

- Two hypothetical salts, LM2 and LQ, have the same molar solubility in [latex]\ce{H2O}[/latex]. If Ksp for LM2 is 3.20 × 10–5, what is the Ksp value for LQ?

- Which of the following carbonates will form first? Which of the following will form last? Explain.

- [latex]{\text{MgCO}}_{3}{K}_{\text{sp}}=3.5\times 1{0}^{-8}[/latex]

- [latex]{\text{CaCO}}_{3}{K}_{\text{sp}}=4.2\times 1{0}^{-7}[/latex]

- [latex]{\text{SrCO}}_{3}{K}_{\text{sp}}=3.9\times 1{0}^{-9}[/latex]

- [latex]{\text{BaCO}}_{3}{K}_{\text{sp}}=4.4\times 1{0}^{-5}[/latex]

- [latex]{\text{MnCO}}_{3}{K}_{\text{sp}}=5.1\times 1{0}^{-9}[/latex]

- How many grams of [latex]\ce{Zn(CN)2}[/latex](s) (117.44 g/mol) would be soluble in 100 mL of [latex]\ce{H2O}[/latex]? Include the balanced reaction and the expression for Ksp in your answer. The Ksp value for Zn(CN)2(s) is 3.0 × 10–16.

Show Selected Solutions

- In dissolution, one unit of substance produces a quantity of discrete ions or polyatomic ions that equals the number of times that the subunit appears in the formula.

- [latex]\begin{array}{ccc}\text{AgI}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons & {\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+& {\text{I}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\\ & x& {x}\end{array}[/latex]

Dissolving AgI(s) must produce the same amount of I– ion as it does Ag+ ion. - [latex]\begin{array}{ccc}{\text{CaCO}}_{3}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons & {\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+& {\text{CO}}_{3}^{2-}\left(aq\right)\\ & {x}& x\end{array}[/latex]

Dissolving [latex]\ce{CaCO3}[/latex](s) must produce the same amount of [latex]\ce{Ca^2+}[/latex] ion as it does [latex]{\text{CO}}_{3}^{2-}[/latex] ion. - [latex]\begin{array}{lll}\text{Mg}{\left(\text{OH}\right)}_{2}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow \hfill & {\text{Mg}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)\hfill & +2{\text{OH}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\hfill \\ \hfill & x\hfill & {\text{2}x}\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

When one unit of [latex]\ce{Mg(OH)2}[/latex] dissolves, two ions of [latex]\ce{OH-}[/latex] are formed for each [latex]\ce{Mg^2+}[/latex] ion. - [latex]\begin{array}{ccc}{\text{Mg}}_{3}{\left({\text{PO}}_{4}\right)}_{2}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons & {\text{3Mg}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+& {\text{2PO}}_{4}^{3-}\left(aq\right)\\ & {3x}& 2x\end{array}[/latex]

One unit of [latex]\ce{Mg3(PO4)2}[/latex] provides two units of [latex]{\text{PO}}_{4}^{3-}[/latex] ion and three units of [latex]\ce{Mg^2+}[/latex] ion. - [latex]\begin{array}{cccc}{\text{Ca}}_{5}{\left({\text{PO}}_{4}\right)}_{3}\text{OH}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons & {\text{5Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+& {\text{3PO}}_{4}^{3-}\left(aq\right)+& {\text{OH}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\\ & {5x}& {3x}& x\end{array}[/latex]

One unit of [latex]\ce{Ca5(PO4)3OH}[/latex] dissolves into five units of [latex]\ce{Ca^2+}[/latex] ion, three units of [latex]{\text{PO}}_{4}^{3-}[/latex] ion, and one unit of [latex]\ce{OH-}[/latex] ion.

- [latex]\begin{array}{ccc}\text{AgI}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons & {\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+& {\text{I}}^{-}\left(aq\right)\\ & x& {x}\end{array}[/latex]

- There is no change. A solid has an activity of 1 whether there is a little or a lot.

- The solubility of silver bromide at the new temperature must be known. Normally the solubility increases and some of the solid silver bromide will dissolve.

- [latex]\ce{CaF2}[/latex], [latex]\ce{MnCO3}[/latex], and [latex]\ce{ZnS}[/latex]; each is a salt of a weak acid and the hydronium ion from water reacts with the anion, causing more solid to dissolve to maintain the equilibrium concentration of the anion

- The answers for each compound are as follows:

- [latex]\text{LaF}_{3}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons\text{La}^{3+}\left(aq\right)+{3F}^{-}\left(aq\right)\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{La}^{3+}\right]\left[\text{F}^{-}\right]^{3}[/latex]

- [latex]\text{CaCO}_{3}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons\text{Ca}^{2+}\left(aq\right)+\text{CO}_{3}^{2-}\left(aq\right)\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Ca}^{2+}\right]\left[\text{CO}_{3}^{2-}\right][/latex]

- [latex]\text{Ag}_{2}\text{SO}_{4}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons2\text{Ag}^{+}\left(aq\right)+\text{SO}_{4}^{2-}\left(aq\right)\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Ag}^{+}\right]^{2}\left[\text{SO}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex]

- [latex]\text{Pb}\left(\text{OH}\right)_{2}\left(s\right)\rightleftharpoons\text{Pb}^{2+}\left(aq\right)+2\text{OH}^{-}\left(aq\right)\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{;}\,\,\,\,\,\,\,{K}_{\text{sp}}=\left[\text{Pb}^{2+}\right]\left[\text{OH}^{-}\right]^{2}[/latex]

- Convert each concentration into molar units. Multiply each concentration by 10 to determine the mass in 1 L, and then divide the molar mass.

- [latex]\ce{BaSeO4}[/latex]

- [latex]\frac{0.{\text{118 g L}}^{-1}}{280.{\text{28 g mol}}^{-1}}=\text{4.21}\times {10}^{-4}\text{}M[/latex]

- K = [Ba2+] [latex]\left[{\text{SeO}}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex] = (4.21 × 10–4)(4.21 × 10–4) = 1.77 × 10–7

- [latex]\ce{Ba(BrO3)2·H2O}[/latex]:

- [latex]\frac{3.0{\text{g L}}^{-1}}{{\text{411.147 g mol}}^{-1}}=\text{7.3}\times {10}^{-3}\text{}M[/latex]

- K = [Ba2+] [latex]{\left[{\text{BrO}}_{3}{}^{-}\right]}^{2}[/latex] = (7.3 × 10–3)(2 × 7.3 × 10–3)2 = 1.6 × 10–6

- [latex]\ce{NH4MgAsO4·6H2O}[/latex]:

- [latex]\frac{0.{\text{38 g L}}^{-1}}{{\text{289.3544 g mol}}^{-1}}=\text{1.3}\times {10}^{-3}\text{}M[/latex]

- K = [latex]\left[{\text{NH}}_{4}{}^{\text{+}}\right][/latex] [Mg2+] [latex]\left[{\text{AsO}}_{4}{}^{3-}\right][/latex] = (1.3 × 10–3)3 = 2.2 × 10–9

- La2(MoO4)3:

- [latex]\frac{0.0{\text{179 g L}}^{-1}}{{\text{757.62 g mol}}^{-1}}=\text{2.36}\times {10}^{-5}\text{}M[/latex]

- K = [La3+]2 [latex]{\left[{\text{MoO}}_{4}{}^{2-}\right]}^{3}[/latex] = (2 × 2.36 × 10–5)2(3 × 2.36 × 10–5)3 = 2.228 × 10–9 × 3.549 × 10–13 = 7.91 × 10–22

- [latex]\ce{BaSeO4}[/latex]

- Let x be the molar solubility.

- Ksp = [latex]\left[{\text{K}}^{\text{+}}\right]\left[{\text{HC}}_{4}{\text{H}}_{4}{\text{O}}_{6}^{-}\right][/latex] = 3 × 10–4 = x2, x = 2 × 10–2M;

- Ksp = [Pb2+][I–]2 = 8.7 × 109 = x(2x)3 = 4x3, x = 1.3 × 10–3M;

- Ksp = [latex]{\left[{\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\right]}^{4}\left[{\text{Fe(CN)}}_{6}{}^{\text{4-}}\right][/latex] = 1.55 × 10–41 = (4x)4x = 256x5, x = 2.27 × 10–9M;

- Ksp = [latex]\left[{\text{Hg}}_{2}{}^{\text{2+}}\right]{\left[{\text{I}}^{-}\right]}^{2}[/latex] = 4.5 × 10–29 = [x][2x]2 = 4x3, x = 2.2 × 10–10M

- The correct concentrations are as follows:

- Ksp = 1.8 × 10–10 = [latex]\ce{[Ag+][Cl-]}[/latex] = x(x + 0.025), where x = [Ag+]. Assume that x is small when compared with 0.025 and therefore ignore it:

- [latex]x=\frac{1.8\times {10}^{-10}}{0.025}=7.2\times {10}^{-9}\text{}M=\left[{\text{Ag}}^{\text{+}}\right],\text{}\left[{\text{Cl}}^{-}\right]=0.02\text{5}M[/latex]

- Check: [latex]\frac{7.2\times {10}^{-9}\text{}M}{0.025\text{}M}\times \text{100%}=\text{2.9}\times {10}^{-5}%[/latex], an insignificant change;

- Ksp = 3.9 × 10–11 = [latex]\ce{[Ca^2+][F-]2}[/latex] = x(2x + 0.00133 M)2, where x = [latex]\ce{[Ca^2+]}[/latex]. Assume that x is small when compared with 0.0013 M and disregard it:

- [latex]x=\frac{\text{3.9}\times {10}^{-11}}{{\left(0.00133\right)}^{2}}=2.2\times {10}^{-5}\text{}M=\left[{\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\right],\text{}\left[{\text{F}}^{-}\right]=0.0013\text{}M[/latex]

- Check: [latex]\frac{\text{2.25}\times {10}^{-5}\text{}M}{0.00133\text{}M}\times \text{100%}=\text{1.69%}[/latex]. This value is less than 5% and can be ignored.

- Find the concentration of [latex]\ce{K2SO4}[/latex]:

- [latex]\frac{\text{19.50 g}}{174.2{\text{60 g mol}}^{-1}}=\text{0.1119 mol}[/latex]

[latex]\frac{0.1119\text{mol}}{0.5\text{L}}=\text{0.2238}M={\text{[SO}}_{4}{}^{2-}][/latex]

Ksp = 1.18 × 10–18 = [Ag+]2 [latex]{\text{[SO}}_{4}{}^{2-}][/latex] = 4x2(x + 0.2238)

[latex]{x}^{2}=\frac{1.18\times {10}^{-18}}{4\left(0.2238\right)}=\text{1.32}\times {10}^{-18}[/latex]

x = 1.15 × 10–9[Ag+] = 2x = 2.30 × 10–9M - Check: [latex]\frac{1.15\times {10}^{-9}}{0.2238}\times 100%=\text{5.14}\times {10}^{-7}[/latex]; the condition is satisfied.

- [latex]\frac{\text{19.50 g}}{174.2{\text{60 g mol}}^{-1}}=\text{0.1119 mol}[/latex]

- Find the concentration of [latex]\ce{OH-}[/latex] from the pH:

- pOH = 14.00 – 11.45 = 2.55

[OH–] = 2.8 × 10–3M

Ksp = 4.5 × 10–17 = [Zn2+][OH–]2 = x(2x + 2.8 × 10–3)2 - Assume that x is small when compared with 2.8 × 10–3:

[latex]x=\frac{4.5\times {10}^{-17}}{{\left(2.8\times {10}^{-3}\right)}^{2}}=\text{5.7}\times 10 - 12\text{}M={\text{[Zn}}^{\text{2+}}\text{]}[/latex] - Check: [latex]\frac{5.7\times {10}^{-12}}{2.8\times {10}^{-3}}\times \text{100%}=\text{2.0}\times {10}^{-7}%[/latex]; x is less than 5% of [OH–] and is, therefore, negligible. In each case the change in initial concentration of the common ion is less than 5%.

- pOH = 14.00 – 11.45 = 2.55

- Ksp = 1.8 × 10–10 = [latex]\ce{[Ag+][Cl-]}[/latex] = x(x + 0.025), where x = [Ag+]. Assume that x is small when compared with 0.025 and therefore ignore it:

- The answers are as follows:

- Ksp = 1.9 × 10–4 = [latex]\ce{[Ti+][Cl-]}[/latex]; Let x = [latex]\ce{[Cl-]}[/latex]:1.9 × 10–4 = (x = 0.025)x

- Assume that x is small when compared with 0.025:

- [latex]x=\frac{1.9\times {10}^{-4}}{0.025}=7.6\times {10}^{-3}\text{}M[/latex]

- Check: [latex]\frac{7.6\times {10}^{-3}}{0.025}\times \text{100%}=\text{30%}[/latex]

- This value is too large to drop x. Therefore solve by using the quadratic equation:

- [latex]\frac{-b\pm \sqrt{{b}^{2}-4ac}}{2a}[/latex]

- x2 + 0.025x – 1.9 × 10–4 = 0

- [latex]\begin{array}{l}{ }x=\frac{-0.025\pm \sqrt{6.25\times {10}^{-4}+7.6\times {10}^{-4}}}{2}=\frac{-0.025\pm \sqrt{1.385\times {10}^{-3}}}{2}\\ =\frac{-0.025\pm 0.0372}{2}=0.00\text{61}M\end{array}[/latex]

- (Use only the positive answer for physical sense.)

- [Ti+] = 0.025 + 0.0061 = 3.1 × 10–2M

- [Cl–] = 6.1 × 10–3

- Assume that x is small when compared with 0.025:

- Ksp = 1.7 × 10–6 = [Ba2+][F–]2:

- Let x = [Ba2+]

- 1.7 × 10–6 = x(x + 0.0313)2 = 1.7 × 10–3M

- Check: [latex]\frac{1.7\times {10}^{-3}}{0.0313}\times \text{100%}=\text{5.5%}[/latex]

- This value is too large to drop x, and the entire equation must be solved. One method to find the answer is to solve by successive approximations. Begin by choosing the value of x that has just been calculated:

- x′(5.4 × 10–5 + 0.0313)2 = 1.7 × 10–3 or

- [latex]x\prime =\frac{1.7\times {10}^{-6}}{1.089\times {10}^{-3}}=\text{1.6}\times {10}^{-3}[/latex]

- A third approximation using this last calculation is as follows:

- x′′(1.7 × 10–3 + 0.0313)2 = 1.7 × 10–6 or

- [latex]x\prime \prime =\frac{1.7\times {10}^{-6}}{1.089\times {10}^{-3}}=\text{1.6}\times {10}^{-3}[/latex]

- This value is well within 5% and is acceptable.

- [Ba2+] = 1.6 × 10–3M

- [F–] = (1.6 × 10–3 + 0.0313) = 0.0329 M;

- Find the molar concentration of the [latex]\ce{Mg(NO3)2}[/latex]. The molar mass of [latex]\ce{Mg(NO3)2}[/latex] is 148.3149 g/mol. The number of moles is [latex]\frac{\text{8.156 g}}{148.314{\text{9 g mol}}^{-1}}=\text{0.05499 mol}[/latex]

- [latex]M=\frac{\text{0.05499 mol}}{\text{2.250 L}}=\text{0.02444 M}[/latex]

- Let x = [latex]\left[{\text{C}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex] and assume that x is small when compared with 0.02444 M.

- Ksp = 8.6 × 10–5 = [Mg2+] [latex]\left[{\text{C}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex] = (x)(x + 0.02444)

- 0.02444x = 8.6 × 10–5

- x = [latex]\left[{\text{C}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex] = 3.5 × 10–3

- Check: [latex]\frac{3.5\times {10}^{-3}}{0.02444}\times \text{100%}=\text{14%}[/latex]

- This value is greater than 5%, so the quadratic equation must be used to solve for x:

- [latex]\begin{array}{l}{}\frac{-b\pm \sqrt{{b}^{2}-4ac}}{2a}\\{x}^{2}+0.02444x - 8.6\times {10}^{-5}=0\\x=\frac{-0.02444\pm \sqrt{5.973\times {10}^{-4}+3.44\times {10}^{-4}}}{2}=\text{}\frac{-0.02444\pm 0.03068}{2}\end{array}[/latex]

- (Use only the positive answer for physical sense.)

- x′ = [latex]\left[{\text{C}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}{}^{2-}\right][/latex] = 3.5 × 10–3M

- [Mg2+] = 3.1 × 10–3 + 0.02444 = 0.0275 M

- (d) pH = 12.700; pOH = 1.300

- [latex]\ce{[OH-]}[/latex] = 0.0501 M; Let x = [latex]\ce{[Ca^2+]}[/latex]

- Ksp = 7.9 × 10–6 = [latex]\ce{[Ca^2+][OH-]^2}[/latex] = (x)(x + 0.050)2

- Assume that x is small when compared with 0.050 M:

- x = [latex]\ce{[Ca^2+]}[/latex] = 3.15 × 10–3 (one additional significant figure is carried)

- Check: [latex]\frac{3.15\times {10}^{-3}}{0.050}\times \text{100%}=\text{6.28%}[/latex]

- This value is greater than 5%, so a more exact method, such as successive approximations, must be used. Begin by choosing the value of x that has just been calculated:

- x′(3.15 × 10–3 + 0.0501)2 = 7.9 × 10–6 or

- [latex]x\prime =\frac{7.9\times {10}^{-6}}{2.836\times {10}^{-3}}=\text{2.8}\times {10}^{-3}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{[Ca^2+]}[/latex] = 2.8 × 10–3M

- [latex]\ce{[OH-]}[/latex] = (2.8 × 10–3 + 0.0501) = 0.053 × 10–2M

- In each case, the initial concentration of the common ion changes by more than 5%.

- Ksp = 1.9 × 10–4 = [latex]\ce{[Ti+][Cl-]}[/latex]; Let x = [latex]\ce{[Cl-]}[/latex]:1.9 × 10–4 = (x = 0.025)x

- The changes in concentration are greater than 5% and thus exceed the maximum value for disregarding the change.

- [latex]\ce{Ca(OH)2: [Ca^2+][OH-]^2}[/latex] = 7.9 × 10–6

- Let x be [latex]\ce{[Ca^2+]}[/latex] = molar solubility; then [latex]\ce{[OH-]}[/latex] = 2x

- Ksp = x(2x)2 = 4x3 = 7.9 × 10–6

- x3 = 1.975 × 10–6

- x = 0.013 M

- [latex]\ce{CaCO3: [Ca^2+][CO3^2-]}[/latex] = 4.8 × 10–9

- Let x be [latex]\ce{[Ca^2+]}[/latex]; then [latex]{\text{[CO}}_{3}^{2-}][/latex] = [Ca2+] = molar solubility

- Ksp = x2 = 4.8 × 10–9

- x = 6.9 × 10–5M

- [latex]\ce{CaSO4·2H2O: [Ca^2+][SO4^2-]}\text{\cdot }\ce{[H2O]^2}[/latex] = 2.4 10–5

- Let x be [latex]\ce{[Ca^2+]}[/latex] = molar solubility = [latex]{\text{[SO}}_{4}^{2-}][/latex]; then [latex]\ce{[H2O]}[/latex] = 2x

- Ksp = (x)(x)(2x)2 = 2.4 × 10–5

- x4 = 6.0 × 10–6

- x = 0.049 M

- This value is more than three times the value given by the Handbook of Chemistry and Physics of (0.014 M) and reflects the complex interaction of water within the precipitate:

- [latex]\ce{CaC2O4·H2O: [Ca^2+][C2O4^2-][H2O]}[/latex] = 2.27 × 10–9

- Let x be [latex]\ce{[Ca^2+]}[/latex] = molar solubility = [latex]\left[{\text{C}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex] = [H2O]

- x3 = 2.27 × 10–9

- x = 1.3 × 10–3M

- In this case, the interaction of water is also complex and the solubility is considerably less than that calculated.

- Ca3(PO4)2: [Ca2+]3 [latex]{\left[{\text{PO}}_{4}^{3-}\right]}^{2}[/latex] = 1 × 10–25

- Upon solution there are three Ca2+ and two [latex]{\text{PO}}_{4}^{3-}[/latex] ions. Let the concentration of Ca2+ formed upon solution be x. Then [latex]\frac{2}{3}x[/latex] is the concentration of [latex]{\text{PO}}_{4}{}^{\text{3-}}:[/latex]

- [latex]{x}^{3}{\left(\frac{2}{3}x\right)}^{2}{x}^{3}=1\times {10}^{-25}=\text{0.4444}{x}^{5}[/latex]

- x = 1 × 10–5M = [Ca2+]

- The solubility is then one-third the concentration of Ca2+, or 4 × 10–6.

- First, find the concentration in a saturated solution of CaSO4. Before placing the CaSO4 in water, the concentrations of Ca2+ and [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex] are 0. Let x be the change in concentration of Ca2+, which is equal to the concentration of [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}:[/latex]

- Ksp = [Ca2+] [latex]\left[{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex] = 2.4 × 10–5

- x × x = x2 = 2.4 × 10–5

- [latex]x=\sqrt{2.4\times {10}^{-5}}[/latex]

- x = 4.9 × 10–3M = [latex]\left[{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex] = [Ca2+]

- Since this concentration is higher than 2.60 × 10–3M, “gyp” water does not meet the standards.

- The amount of CaSO4·2H2O that dissolves is limited by the presence of a substantial amount of [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex] already in solution from the 0.010 M [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}{}^{-}[/latex]. This is a common-ion problem. Let x be the change in concentration of Ca2+ and of [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex] that dissociates from CaSO4:

- [latex]{\text{CaSO}}_{4}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow {\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{SO}}_{4}{}^{\text{2-}}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

- Ksp = [Ca2+] [latex]{\text{[SO}}_{4}^{2-}][/latex] = 2.4 × 10–5

- Addition of 0.010 M [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex] generated from the complete dissociation of 0.010 M SO4 gives

- [x][x + 0.010] = 2.4 × 10–5

- Here, x cannot be neglected in comparison with 0.010 M; the quadratic equation must be used. In standard form:

- x2 + 0.010x – 2.4 × 10–5 = 0

- [latex]x=\frac{-0.01\pm \sqrt{1\times {10}^{-4}+9.6\times {10}^{-5}}}{2}=\frac{-0.01\pm 1.4\times {10}^{-2}}{2}[/latex]

- Only the positive value will give a meaningful answer:

- x = 2.0 × 10–3 = [Ca2+]

- This is also the concentration of CaSO4·2H2O that has dissolved. The mass of the salt in 1 L is

- Mass (CaSO4·2H2O) = 2.0 × 10–3 mol/L × 172.16 g/mol = 0.34 g/L

- Note that the presence of the common ion, [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex], has caused a decrease in the concentration of Ca2+ that otherwise would be in solution:

- [latex]\sqrt{2.4\times {10}^{-5}}=\text{4.9}\times {10}^{-5}\text{}M[/latex]

- In each of the following, allow x to be the molar concentration of the ion occurring only once in the formula.

- Ksp = [Ag+][Cl–] = 1.5 – 10–16 = [x2], [x] = 1.2 – 10–8M, [Ag+] = [I–] = 1.2 × 10–8M

- Ksp = [latex]{{\text{[Ag}}^{\text{+}}]}^{2}\left[{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex] = 1.18 × 10–5 = [2x]2[x], 4x3 = 1.18 × 10–5, x = 1.43 × 10–2M

As there are 2 Ag+ ions for each [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex] ion, [Ag+] = 2.86 × 10–2M, [latex]{\text{[SO}}_{4}^{2-}][/latex] = 1.43 × 10–2M; (c) Ksp = [Mn2+]2[OH–]2 = 4.5 × 10–14 = [x][2x]2, 4x3 = 4.5 × 10–14, x = 2.24 × 10–5M. - Since there are two OH– ions for each Mn2+ ion, multiplication of x by 2 gives 4.48 × 10–5M. If the value of x is rounded to the correct number of significant figures, [Mn2+] = 2.2 × 10–5M. [OH–] = 4.5 × 10–5M. If the value of x is rounded before determining the value of [OH–], the resulting value of [OH–] is 4.4 × 10–5M. We normally maintain one additional figure in the calculator throughout all calculations before rounding.

- Ksp = [Sr2+][OH–]2 = 3.2 × 10–4 = [x][2x]2, 4x3 = 3.2 × 10–4, x = 4.3 × 10–2M.

Substitution gives [Sr2+] = 4.3 × 10–2 M, [OH–] = 8.6 × 10–2M - Ksp = [Mg2+]2[OH–]2 = 1.5 × 10–11 = [x][2x]2, 4x3 = 1.5 × 10–11, x = 1.55 × 10–4M, 2x = 3.1 × 10–4.

Substitution and taking the correct number of significant figures gives [Mg2+] = 1.6 × 10–4M, [OH–] = 3.1 × 10–4M. If the number is rounded first, the first value is still [Mg2+] = 1.6 × 10–4M, but the second is [OH–] = 3.2 × 10–4M.

- In each case the value of Ksp is found by multiplication of the concentrations raised to the ion’s stoichiometric power. Molar units are not normally shown in the value of K.

- TlCl: Ksp = (1.4 × 10–2)(1.2 × 10–2) = 2.0 × 10–4

- Ce(IO3)4: Ksp = (1.8 × 10–4)(2.6 × 10–13)4 = 5.1 × 10–17

- Gd2(SO4)3: Ksp = (0.132)2(0.198)3 = 1.35 × 10–4

- Ag2SO4: Ksp = (2.40 × 10–2)2(2.05 × 10–2) = 1.18 × 10–5

- BaSO4: Ksp = (0.500)(2.16 × 10–10) = 1.08 × 10–10

- The answers are as follows:

- [latex]{\text{CaCO}}_{3}:{\text{CaCO}}_{3}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow {\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{CO}}_{3}{}^{2-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

- Ksp = [Ca2+] [latex]{\text{[CO}}_{3}^{2-}][/latex] = 4.8 × 10–9

- test Ksp against Q = [Ca2+] [latex]{\text{[CO}}_{3}^{2-}][/latex]

- Q = [Ca2+] [latex]{\text{[CO}}_{3}^{2-}][/latex] = (0.003)(0.003) = 9 × 10–6

- Ksp = 4.8 × 10–9 < 9 × 10–6

- The ion product does exceed Ksp, so CaCO3 does precipitate.

- [latex]{\text{Co(OH)}}_{2}:{\text{Co(OH)}}_{2}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow {\text{Co}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{2OH}}^{-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

- Ksp = [Co2+][OH–]2 = 2 × 10–16

- test Ksp against Q = [Co2+][OH–]2

- Q = [Co2+][OH–]2 = (0.01)(1 × 10–7)2 = 1 × 10–16

- Ksp = 2 × 10–16 > 1 × 10–16

- The ion product does not exceed Ksp, so the compound does not precipitate.

- CaHPO4: (Ksp = 5 × 10–6):

- Q = [Ca2+] [latex]{\text{[HPO}}_{4}^{2-}][/latex] = (0.01)(2 × 10–6) = 2 × 10–8 < Ksp

- The ion product does not exceed Ksp, so compound does not precipitate.

- Pb3(PO4)2: (Ksp = 3 × 10–44):

- Q = [Pb2+]3 [latex]{{\text{[PO}}_{4}^{3-}]}^{2}[/latex] = (0.01)3(1 × 10–13)2 = 1 × 10–32 > Ksp

- The ion product exceeds Ksp, so the compound precipitates.

- [latex]{\text{CaCO}}_{3}:{\text{CaCO}}_{3}\left(s\right)\longrightarrow {\text{Ca}}^{\text{2+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{CO}}_{3}{}^{2-}\left(aq\right)[/latex]

- Precipitation of [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex] will begin when the ion product of the concentration of the [latex]{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}[/latex] and Ba2+ ions exceeds the Ksp of BaSO4.

- Ksp = 1.08 × 10–10 = [Ba2+] [latex]\left[{\text{SO}}_{4}^{2-}\right][/latex] = (0.0758) [latex]{\text{[SO}}_{4}^{2-}][/latex]

- [latex]\left[\text{SO}_{4}^{2-}\right]=\frac{1.08\times{10}^{-10}}{0.0758}=\text{1.42}\times{10}^{-9}M[/latex]

- Precipitation of Ag3PO4 will begin when the ion product of the concentrations of the Ag+ and [latex]{\text{PO}}_{4}{}^{\text{3-}}[/latex] ions exceeds Ksp: