4

Captain Cook’s Endeavour voyage in 1770 was part of a growing European presence in the Pacific from the late eighteenth century onwards. While the Manila Galleon had plied its familiar route since 1565, Spanish exploration of the region was limited. Similarly, English pirates might have pursued the Galleon, but they had not mapped the Ocean. And despite the voyages of Abel Tasman and Jacob Roggeveen into the Pacific itself, the Dutch presence had largely remained west of the Australian continent, and had concentrated on avoiding undesirable landfall, rather than exploration. This changed as European technology improved and European explorers became better able to meet the challenges of reaching and navigating Oceania. But while their technology had improved, in many ways European explorers in this period were seeking the same things in the Pacific as their predecessors, and they were similarly guided by preconceptions when interpreting and reporting their Pacific encounters.

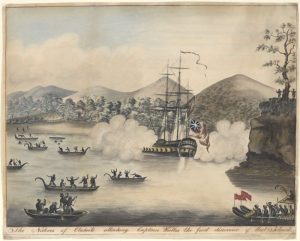

In the late eighteenth century, the number of Europeans entering the Pacific increased markedly, and European exploration of the region became more systematic. As a result, more islands were encountered, and the positions of those islands began to be calculated and recorded with some degree of accuracy. Key in this process of increasing contact between Europeans and Pacific Islanders was the island of Tahiti. That island was first encountered by Europeans on 18 June 1767, when it was sighted from the Dolphin (a ship under the command of Samuel Wallis). The Dolphin was on its second voyage to the Pacific, the first had taken place in 1764-5 under John Byron. While European vessels were beginning to reach the Pacific repeatedly by this point, they were often short of food supplies and drinking water during their voyages across the vast ocean. When it reached Tahiti in 1767 the Dolphin was in desperate need of supplies, and the officers could not determine how far away the nearest known port lay. As a result, the desperate crew resorted to violence in the face of local people who asserted their control over their land and resources. After suffering significant casualties from European canons and firearms, the Tahitians sought to control their insistent guests through overwhelming hospitality. In doing so, they helped create a persistent European myth of luscious Pacific places and people.

On the Dolphin’s return to England Tahiti was identified as an excellent location from which to observe a rare astronomical event, the transit of Venus. Accurate measurements of the transit, taken from widely flung regions of the planet, would provide data for calculations to determine distances between the sun and its planets. The Endeavour was dispatched in 1768 for what would be a three-month stay in Tahiti. During that time Tahiti was accurately charted, and its longitude calculated, meaning that it could be placed on European maps with certainty.

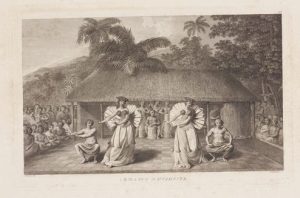

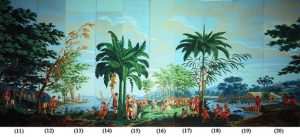

In the time between the voyages of the Dolphin and the Endeavour, the French naval explorer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville also ‘discovered’ Tahiti. Informed by their encounter with the English, the Tahitians placated their visitors from the very first, and created a perception among the French voyagers that a place of free love and plenty of the type only dreamed of in Europe actually existed in the Pacific. Thus, the myth of Tahiti took root in Europe, bolstered by multiple accounts from different voyages that either ignored the violence of Wallis’s initial encounter, or were ignorant of it. In creating the myth of Tahiti, Europeans continued a tradition of using recently encountered societies to critique their own: while European philosophers might speculate on the benefits of living closely with nature and participating in free love, they were basing their ideas on vague impressions, not close and accurate observations of island societies. Their assessments were of European civilisation and of their own societies, and their knowledge of Pacific Islanders was slight.

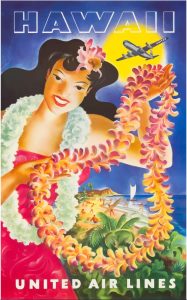

The perception of Tahiti as an earthly paradise continues to the present, supported by a tourism industry that deliberately feeds these old European myths. And Tahiti is not the only region of the Pacific to have been interpreted as paradise by European visitors. Hawai’i became a significant resupply port in the fur trade between North America and China, and was annexed by the United States in 1898. By the time of annexation, the islands were already a tourist destination and were connected to the United States by subsidised steamship lines. Hawaiian tourism intensified through the twentieth century, and the image of Pacific Island paradises persists into the twenty-first. Recent tourism campaigns by Pacific Island nations tap into very old European ideas about the regions at the edge of the map, and what might be found there.

The inhabitants of different regions of the Pacific were interpreted differently, in line with Europeans’ varied expectations of ‘savages’. Tahitians, Hawaiians, and at times Samoans were interpreted as ‘soft’ savages and subjected to a range of related interpretations. These islanders were interpreted as close to nature, useful and diligent (suitable as servants, but not equal to Europeans), and often as being at risk of decline or dying out through their contact with European civilisation. This fear of the Pacific representing a fading golden age, often associated with Europe’s classical age, was persistent and is exemplified in Paul Gauguin’s images of Tahitians, painted in the late nineteenth century. In other places explorers recognised that they were unwelcome, and typified Pacific Islanders as ‘hard’ savages who were warlike, uncivilised, and unfriendly. In those places Europeans tended to interpret Pacific Islanders as leading lives that were ‘solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short’ in line with Thomas Hobbes’s earlier description of what it was to live without effective government. These visions of Islanders had their origins in Europe, rather than the Pacific.

The journals kept by European explorers record the early period of contact between Europeans and Pacific peoples. They are remarkable documents that provide eyewitness accounts of eighteenth-century island societies, but their contents record a reality filtered through European expectations. Since the 1960s anthropologists, historians, and other scholars of the Pacific, have worked to decode these observations, highly coloured by European preconceptions, and to understand the island societies of that time in their own terms. Despite the European expectations that coloured explorer observations, recent scholarship has demonstrated that the explorers’ journals offer insights into Islander experiences of this period of encounter and shed light on the way in which European misunderstandings at times led to offence and conflict as they unwittingly insulted their island hosts or acted in culturally unacceptable ways.

The late eighteenth century marked an acceleration in contact between European and Pacific peoples. European technology allowed voyaging to become more manageable and the location of islands to be recorded with some accuracy. However, Europe’s embrace of science and technology did not free Europeans of their expectations, and European explorer journals from this period offer insight into both Pacific and European societies. The Pacific that was becoming known to Europe was in many ways a distorted reflection of European societies, as Europe used the Pacific to think with. The images of island paradises that European thinkers built using explorers’ accounts of their experiences were sufficiently compelling that they can still be detected in the present.

Links

Explorer Journals

Bougainville, Louis de. Bougainville’s Voyage Round the World in the Frigate La Boudeuse 1766, 1767, 1768 & 1769. Translated by John F. Fegan. Internet Arcive, 2013. https://archive.org/details/BougainvillesVoyageRoundTheWorldInTheFrigateLaBoudeuse17669EnglishTranslation2014.docx

Byron, John, Samuel Wallis, Philip Carteret, James Cook, and Joseph Banks. An Account of the Voyages Undertaken by the Order of His Present Majesty for Making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere, and Successively Performed by Commodore Byron, Captain Wallis, Captain Carteret, and Captain Cook, in the Dolphin, the Swallow, and the Endeavour: Drawn up from the Journals which were Kept by the Several Commanders, and from the Papers of Joseph Banks, esq, vol. I. Edited by John Hawkesworth. London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1773. https://archive.org/details/b30413801_0001/page/n7/mode/2up

Byron, John, Samuel Wallis, Philip Carteret, James Cook, and Joseph Banks. An Account of the Voyages Undertaken by the Order of His Present Majesty for Making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere, and Successively Performed by Commodore Byron, Captain Wallis, Captain Carteret, and Captain Cook, in the Dolphin, the Swallow, and the Endeavour: Drawn up from the Journals which were Kept by the Several Commanders, and from the Papers of Joseph Banks, esq, vol II. Edited by John Hawkesworth. London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1773. https://archive.org/details/b30413801_0002/page/n5/mode/2up Edited by John Hawkesworth. London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1773

Byron, John, Samuel Wallis, Philip Carteret, James Cook, and Joseph Banks. An Account of the Voyages Undertaken by the Order of His Present Majesty for Making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere, and Successively Performed by Commodore Byron, Captain Wallis, Captain Carteret, and Captain Cook, in the Dolphin, the Swallow, and the Endeavour: Drawn up from the Journals which were Kept by the Several Commanders, and from the Papers of Joseph Banks, esq, vol III. Edited by John Hawkesworth. London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1773.https://archive.org/details/accountofvoyages03hawk/mode/2up

Edwards, Edward, and George Hamilton. Voyage of H.M.S. Pandora Despatched to Arrest the Mutineers of the ‘Bounty’ in the South Seas, 1790-1791. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/22834/22834-h/22834-h.htm. London: Francis Edwards, 1915

Maps and online resources

Australian National University. “Maps Online”. Last updated January24, 2022.

Video material

Further videos:

A tourist view of Hula, presented by Joe O’Neil and the National Film and Sound Archive.

Open access secondary sources

Campbell, C. “The Culture of Culture Contact: Refractions from Polynesia.” Journal of World History 14, no. 1 (March, 2003): 63-86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20079009

Claessen, Henri J. M. “The Merry Maidens of Matavai: A Survey of the Views of Eighteenth-Century Participant Observers and Moralists.” Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde 153, no. 2 (1997): 183–210. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27864831

Farber, David and Beth Bailey. “The Fighting Man as Tourist: The Politics of Tourist Culture in Hawai’i During World War II.” Pacific Historical Review 65, no. 4 (1996): 641–60. https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/21431/Farber_Bailey_1996.pdf;jsessionid=F0FAAD72EA83E211D982F2ECC0433781?sequence=1 65, no.4 (1996): 641-660

Halter, Nicholas. Australian Travellers in the South Seas. Canberra: ANU Press, 2021. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1h45mfk

Howe, K. R. “The Fate of the ‘Savage’ in Pacific Historiography.” New Zealand Journal of History 11, no. 2, (1977): 137-154. http://www.nzjh.auckland.ac.nz/docs/1977/NZJH_11_2_04.pdf

Pearson, W. H. “The Reception of European Voyagers on Polynesian Islands, 1568-1797.” Journal de la Société des Océanistes 27 (1970): 121-154. https://www.persee.fr/doc/jso_0300-953x_1970_num_26_27_2151

Other secondary sources

Bell, Leonard. “Eyeing Samoa: People, Places, and Spaces in Photographs of the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries” in Tropical Visions in an Age of Empire, edited by Felix Driver and Luciana Martins, 156-174. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Dening, Greg. Beach Crossings: Voyaging Across Times, Cultures and Self. Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing, 2004.

Edmond, Martin. Zone of the Marvellous: In Search of the Antipodes. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2009.

Richards, Rhys. “On Using Pacific Shipping Records to Gain New Insights into Culture Contact in Polynesia before 1840.” Journal of Pacific History, 43 no. 3 (2008): 375-382.

Salmond, Anne. Aphrodite’s Island: The European Discovery of Tahiti. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.