16

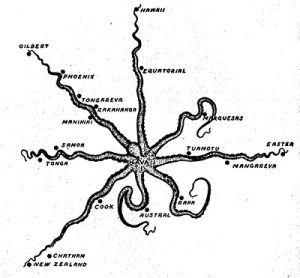

Published in 1993, the book A New Oceania: Rediscovering our Sea of Islands marked the re-imagining of the Pacific as a network of islands, resources, people and innovations, rather than a largely empty ocean dotted with small and isolated specks of land. That reimagining of the Pacific (which included the re-writing of Pacific discovery to include the point of view of islanders and the recognition that the Pacific had already been thoroughly explored before the arrival of Europeans) was a product of the late-twentieth century and the emergence of Māori and Pasifika voices and sensibilities.

The reanalysis of explorers’ journals that began in the 1960s offered new insights into Islander experiences when encountering Europeans. The timing of this scholarship was significant, as was its determination to strip away European preconceptions and projections in order to understand the behaviour of Islanders as rational actors with their own world views. It came as indigeneity became a source of pride, as university education become more widely available, and as the presence of historians and anthropologists who were themselves Islanders increased. The expansion of academic institutions to include more diverse scholars was of immeasurable benefit in furthering understandings of the past (and of the present).

Even in the first half of the twentieth century the significant Māori scholar Te Rangi Hīroa worked to reclaim the power of Māori tradition and to assert the achievements of Pacific navigators. His book Vikings of the Sunrise was published in 1938 during his tenure as the director of the Bishop Museum in Honolulu. During the course of his career Hīroa practised medicine, served as a member of the New Zealand parliament, served with the Māori Battalion (including at Gallipoli), worked in public health, and then developed his interests and expertise in the practice of anthropology. Vikings of the Sunrise included biographical reflections, and a passionate account of the skill and daring required to discover the islands of the Pacific. While some of the details of Hīroa’s account have been refined by later archaeologists and anthropologists, his account remains eminently readable and reasonably accurate in outline. Its assertion of pride in the skills, courage, and achievements of the ancestors make it part of the rediscovery by Pasifika of the significance of their place in the world.

Hīroa was an early herald of a Māori renaissance that became more pronounced after 1960. The American civil rights movement had an influence in Aotearoa (New Zealand), and in Aotearoa land rights became a prominent point of discussion. Linked to issues of historical grievance and the need for redress were actions that aimed to secure taonga (Māori cultural treasures), including the promotion of Te Reo (the Māori language). The Treaty of Waitangi, signed in 1840 by many Māori chiefs and by representatives of the British Crown, gained new significance in political life in the late twentieth century. In 1975 the Waitangi Tribunal was established by the government, in 1985 it began investigating historical land claims, and in the late 1980s the process of recognising and enacting the provisions of the Treaty began. That process included the return of land and resources, and the recognition and protection of taonga.

The work of Hīroa was exceptional, and until late in the twentieth century other authors often represented Pacific navigators as stumbling across land while in distress, rather than deliberately exploring the Pacific. This interpretation of Pacific exploration was supported by evidence of the distress of European explorers as they struggled to cope with navigating the vast Pacific, and by lack of evidence in the form of traditional Polynesian voyaging canoes. Within the Pacific, Islanders had quickly adopted European technology including shipbuilding methods, and after the early period of contact traditional craft were no longer used for significant journeys within Polynesia. During the 1970s movements to recapture traditional navigational techniques and voyaging technology became part of the cultural renaissance taking place within the Pacific, particularly in Hawai’i. Academics played a role in recognising the persistence and reliability of traditional navigation techniques still used in some parts of Micronesia, and in locating descriptions of traditional Polynesian canoes present within the journals of the European explorers.

Hawai’i was an important centre for the rediscovery of Pacific navigation: the Polynesian Voyaging Society was founded in Honolulu in 1973, and in 1975 the Hōkūle’a was launched. That vessel was built on traditional lines using modern materials. In 1976 it completed a return voyage between Hawai’i and Tahiti using traditional navigational techniques and demonstrating that traditional vessels and traditional navigators could reliably cross the vast distances of Polynesia. The Hōkūle’a has continued to undertake significant journeys, and other traditional vessels have been built throughout Polynesia.

Reconstructed voyaging demonstrates the reliability of Polynesian canoe building and navigation. It is a source of mana (prestige), and a reminder of the adventurous nature of the first exploration of the Pacific. Traditional voyages have also supported a pan-Oceanic identity, connecting Polynesian people across a range of island nations. Cooperation based on a common tradition has been made visible in flotillas of traditional vessels originating from different islands. The connections created through traditional voyaging are part of a response by Pacific peoples to European colonialism, and mark a reclaiming of their disrupted histories. The connections forged by traditional voyaging reach across national borders and include indigenous people on the fringes of the Pacific. The location of the Polynesian Voyaging Society within the United States, and the need for large trees from which to create canoes, has led to the involvement of Alaskan first nations groups within the voyaging movement, and those ties now extend from Alaska throughout the Pacific.

The emergence of Covid-19 disrupted plans for commemorating the 250th anniversary of James Cook’s Endeavour voyage in Australia in 2020. Commemorations had already occurred in Aotearoa before Covid-19 required the cancellation of large public events. Those commemorations included debates about the significance of Cook’s arrival, about the colonial history that followed first contact, and about the appropriateness of celebrating Cook’s journey when it involved violence and miscommunication, and acted as a forerunner to settler colonialism. A highly visible part of the commemoration was the Tuia 250 fleet, comprised of traditional vessels and tall ships. In addition, in Aotearoa Cook commemorations of the Endeavour’s voyage built on a growing awareness of the significance of the Tahitian navigator Tupaia to its success.

Across the Pacific, the history of Pacific exploration is being rewritten. European explorers and their journals have a role to play in that history: their efforts and experiences are intriguing and confronting, and the records they created provide a cloudy window into the societies they encountered and the traditions of navigation that facilitated the original exploration of the Pacific. That original exploration was an astounding feat of technical skill and courage, and it is now a source of pride for people across the Pacific.

Links

Video material

Open access secondary sources

Breen, Claire, Alexander Gillespie, Robert Joseph, Valmaine Toki. “Putting Aotearoa on the Map: New Zealand has Changed its Name Before, Why Not Again?” The Conversation, October 6, 2021. https://theconversation.com/putting-aotearoa-on-the-map-new-zealand-has-changed-its-name-before-why-not-again-168651

Dening, Greg. “Encompassing the Sea of Islands: A Most Remarkable Beach Crossing.” Commonplace 5, no. 2 (January, 2005). http://commonplace.online/article/encompassing-the-sea-of-islands-a-most-remarkable-beach-crossing/

Hayden, Leonie. “Te Rā the Sail, Last of its Kind.” The Spinoff, August 31, 2019. https://thespinoff.co.nz/atea/atea-otago/31-08-2019/te-ra-the-sail-last-of-its-kind

Hīroa, Te Rangi. Vikings of the Sunrise, New Zealand ed. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs, 1954. https://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-BucViki-t1-front-d1-d1.html

New Zealand Government. “Tuia te Muka Tangata ki Uta. Weaving People Together for a Shared Future.” Accessed March 30 2022. https://mch.govt.nz/tuia250

Other secondary sources

Arvin, Maile Renee. Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai`i and Oceania. Durham: Duke University Press, 2019.

Finney, Ben. Voyage of Rediscovery: A Cultural Odyssey Through Polynesia. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Hau’ofa, Epeli (ed). A New Oceania: Rediscovering our Sea of Islands. Suva, Fiji: School of Social and Economic Development, University of the South Pacific, 1993.

Howe, Kerry. The Quest for Origins: Who first discovered and settled the Pacific Islands? Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2003.

Matsuda, Matt K. “About Ancestors,” Journal of Pacific History 56, no. 3 (2021): 258-273.