1

When Europeans set out across the Atlantic they were equipped with ideas of what they would find, and those ideas were largely medieval. The medieval period in Europe lasted roughly 1000 years, beginning with the disintegration of the western Roman Empire, and ending as European exploration of the wider world gathered pace. While medieval Europe spanned a long period of time, a large geographic area, and a range of cultures, it was unified by a Christian worldview, by common political structures, and by a recognition of Europe as a meaningful entity. This worldview influenced how Europeans behaved in new places, and how they interpreted what they found there.

Medieval European understandings of the wider world can be traced in the maps produced in that period. Mappae mundi (world maps) of the period depict the important elements of the world, although they sought to explain the world rather than to serve as a basis for navigation. Other medieval maps engaged with physical geography, among them the Catalan Atlas (which followed the style of nautical charts). Both types of map offer insights into how Europeans viewed the world beyond Europe, and both indicate the limited extent of European knowledge. The mappae mundi are particularly fascinating as they offer insight into what Europeans believed, hoped, and feared about the wider world.

A variety of sources were consulted in the construction of mappae mundi. The Hereford mappa mundi is a large and elaborate world map that was produced in the British Isles in c.1290 and has been held by Hereford Cathedral since 1682. At the centre of this map is Jerusalem, and a large number of biblical sites (including the Tower of Babel) can be identified. The map provides insight into medieval European minds: the wealth of biblical sites indicates the significance of Christianity, while the presence of buildings the map-makers knew no longer existed indicates that such maps offered a view of the world that was about more than mere physical reality.

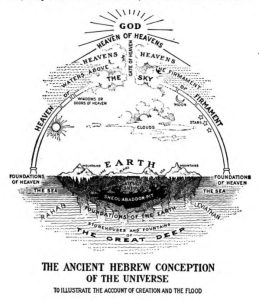

The significance of the Bible as a source of geographical knowledge was problematic, as its text is largely unconcerned with the physical structure of the world, although it contains sections that hint at it. Those hints, expanded and connected, indicate that the world is flat and stationary. Despite this, while some medieval Europeans might have lived on a flat earth, knowledge of Greek thought and mathematics permeated medieval Europe, and medieval kings grasped orbs to show their power over a spherical world. Even the disc shape of mappae mundi is misleading—those creating the maps sought to depict the interesting parts of a globe, while making good use of a flat surface. Including featureless ocean would have wasted map making materials.

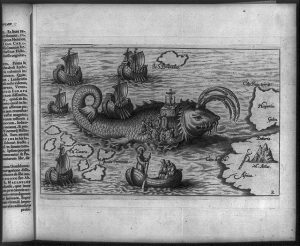

Instead of being taken entirely literally, biblical influences on European understanding of geography were powerful but indirect. Christian logic is apparent in depictions and descriptions of the world. As a result of that logic Jerusalem is the centre of a world girt by the ocean sea, and so routes to it necessarily travel uphill. Similarly, the Garden of Eden exists in the east, but in order to make it impervious to Noah’s flood it floats above the surface of the world. And as a result of the significance of the Bible, Asia dominates the world maps produced in medieval Europe because of the region’s profusion of biblical sites, and because of the wealth it was known to contain. Other sources also informed mappae mundi. Popular stories about Alexander the Great contributed famous people and fabulous animals (sometimes expanding on characters present within the Bible) to the maps. Arabian tales led to the inclusion of legendary islands off the coast of India.

Written accounts of travel also informed medieval geographers: accounts of the travels of Marco Polo and of Sir John Mandeville were both popular late in the medieval period. Polo’s account of his travels as far as China were first published in c.1300. While his account is now recognised as providing accurate information about China in the late thirteenth century, in medieval Europe many considered it unbelievable as it did not accord with expectations of the region. In contrast, the Travels of John Mandeville appeared in c.1360. That account of a journey around the world and back again included descriptions of the wonderous animals and people familiar from mappae mundi, and it was generally accepted as a truthful account of the wider world. Polo’s and Mandeville’s accounts were both consulted by Columbus, and both were familiar to European explorers in the early modern period.

Other accounts of real travels received less attention than Mandeville’s fictional travels. Within the Icelandic Sagas are two accounts of Leif Erikson and his expedition reaching Vinland (North America) in c.1000. Archaeological evidence indicates there was a Viking presence in Newfoundland at that time, although the onset of the little ice age and the increasing difficulties of navigating the Atlantic near the Arctic Circle meant that presence was only temporary. The Icelandic accounts of Vinland did not influence medieval European views of the way in which the world was structured.

The sagas were not the only written traditional stories that dealt with travel across the Atlantic. The story of St Brendan of Ardfert and Clonfert (recorded as Navigatio Brendani in the eleventh century) hints that the Irish discovered the Americas. Born in 484, St Brendan was reported to have undertaken a seven-year voyage that included celebrating Mass on the back of a whale and finding a brightly lit land with a great river that he explored for 40 days without finding its other coast. St Brendan’s Isle regularly appeared on European maps until the sixteenth century. Similarly, a fifteenth-century story had the Welsh Prince Madoc discovering the Americas in 1170.

The maps and tales produced in medieval Europe provide insight into the expectations of the European explorers who first crossed the Atlantic and who then entered the Pacific. They also provide insight into their motivations: Asia looms large on medieval world maps. It is the source of desirable goods, and the east held the promise of wealth and adventure. Medieval European maps might populate the rest of the world with strange beasts and men, but Asia’s wealth made it worth reaching. When Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 Europe’s main trading route with Asia was severed, and European efforts to find other ways to access the wealth of the East triggered European exploration of the wider world.

Links

Explorer Journals

Mandeville, John. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville. Edited by David Price. London: Macmillan and Co Ltd, 1900. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/782/782-h/782-h.htm

Polo, Marco. The Travels of Marco Polo. Vol. 1. Transcribed by Rustichello of Pisa. Edited by Henri Cordier. Translated by Henry Yule. London: Murray, 1920. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10636

Polo, Marco. The Travels of Marco Polo. Vol. 2. Transcribed by Rustichello of Pisa. Edited by Henri Cordier. Translated by Henry Yule. London: Murray, 1920. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/12410

O’Donoghue, Denis. Brendaniana: St. Brendan the Voyager in Story and Legend. Dublin: Browne & Nolan, 1893. https://archive.org/details/brendanianastbr00odogoog/page/n16/mode/2up

O’Donoghue, Denis. “Nauigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis” [The Voyage of St Brendan the Abbot]. https://markjberry.blogs.com/StBrendan.pdf (Note: This is a description of voyage without supplementary material.)

Maps and online resources

Cresques, Abraham. Atlas de cartes marines. (The Catalan Atlas). c.1370-1380

Hereford Cathedral. “Mappa Mundi.”

Virtual Mappa: Digital Editions of Medieval Maps of the World.

Open Access Secondary Sources

Anderson, John D. “The Navigatio Brendani: A Medieval Best Seller.” Classical Journal 83, no. 4 (April-May 1988): 315-322. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3297848?seq=1 83, no.4 (1988): 315-322

Ducza, Matthew. “Medieval World Maps: Diagrams of a Christian Universe.” University of Melbourne Collections 12 (2013): 8-13. https://museumsandcollections.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/1379050/04_Ducza_MedievalMaps12.pdf

Firth-Godbehere, Richard. “The Purpose of Maps at the Time of the Crusades (A brief look).” (2012). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256420979_The_Purpose_of_Maps_at_the_Time_of_the_Crusades_A_brief_look

Greenlee, John Wyatt. “Historia Cartarum: Meditations on the Historical Production of Spaces.” Last modified 2020. https://historiacartarum.org/

Jolly, Margaret. “Imagining Oceania: Indigenous and Foreign Representations of a Sea of Islands.” The Contemporary Pacific 19, no. 1 (2007): 508-545. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23724907

Pischke, G. “The Ebstorf Map: Tradition and Contents of a Medieval Picture of the World”. History of Geo- and Space Sciences 5 (2014): 155–161. https://hgss.copernicus.org/articles/5/155/2014/hgss-5-155-2014.pdf

Other Secondary Sources

Edson, Evelyn. “The Medieval World View: Contemplating the Mappamundi.” History Compass 8, no.6 (2010): 503-517.