64 10.5 Mechanisms for Plate Motion

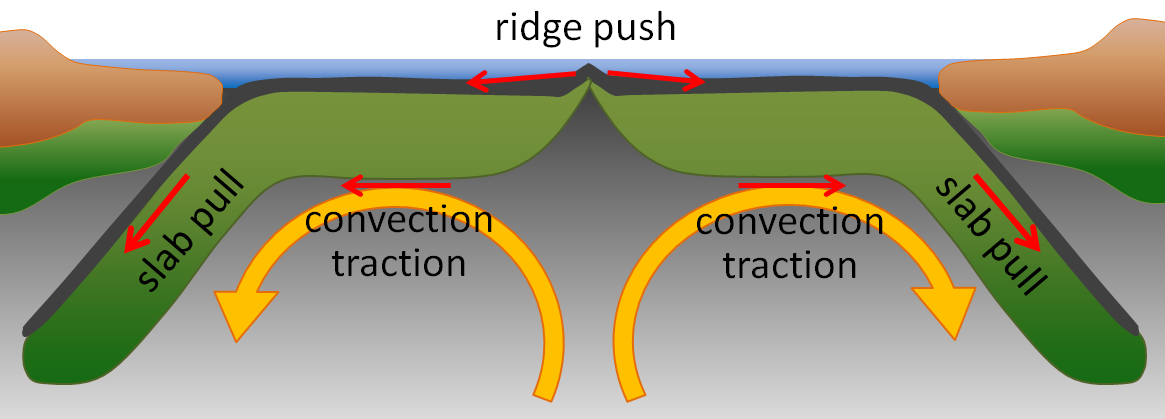

It has been often repeated in this text and elsewhere that convection of the mantle is critical to plate tectonics, and while this is almost certainly so, other forces likely play a significant role. One side in the argument holds that the plates are only moved by the traction caused by mantle convection. The other side holds that traction plays only a minor role and that two other forces, ridge-push and slab-pull, are more important (Figure 10.5.1). Some argue that the real answer lies somewhere in between.

Kearey and Vine (1996)[1] have listed some compelling arguments in favour of the ridge-push/slab-pull model, as follows: (a) plates that are attached to subducting slabs (e.g., Pacific, Australian, and Nazca Plates) move the fastest, and plates that are not (e.g., North American, South American, Eurasian, and African Plates) move significantly slower; (b) in order for the traction model to apply, the mantle would have to be moving about five times faster than the plates are moving (because the coupling between the partially liquid asthenosphere and the plates is not strong), and such high rates of convection are not supported by geophysical models; and (c) although large plates have potential for much higher convection traction, plate velocity is not related to plate area.

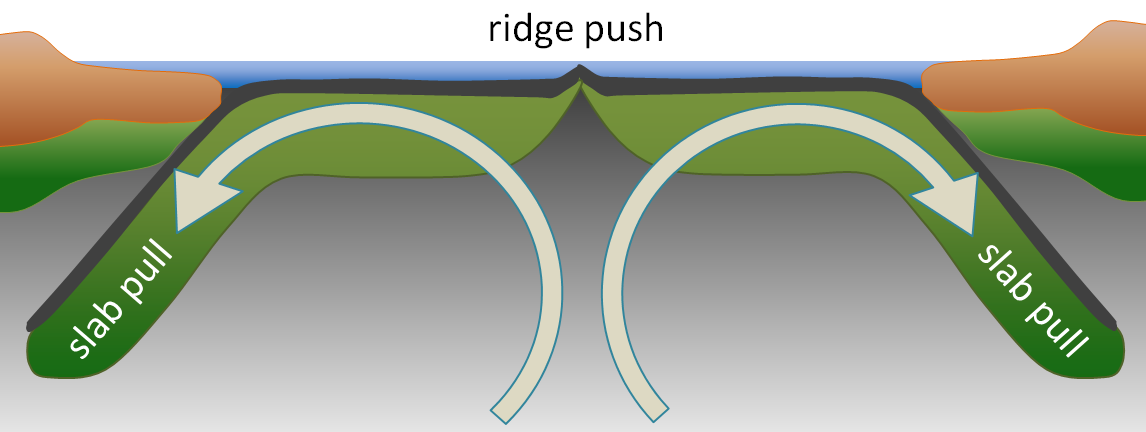

In the ridge-push/slab-pull model, which is the one that has been adopted by most geologists working on plate-tectonic problems, the lithosphere is the upper surface of the convection cells, as is illustrated in Figure 10.5.2.

Although ridge-push/slab-pull is the widely favoured mechanism for plate motion, it’s important not to underestimate the role of mantle convection. Without convection, there would be no ridges to push from because upward convection brings hot buoyant rock to surface. Furthermore, many plates, including our own North American Plate, move along nicely—albeit slowly—without any slab-pull happening.

Image Descriptions

Figure 10.5.1 image description: In this model, there are three forces working to move the plates. Ridge-push forces cause two plates to pull apart on the surface. Slab-pull forces pull the plates down. This movement of out and down is also encouraged by convection traction, or clockwise and counterclockwise currents that are present beneath the plates. [Return to Figure 10.5.1]

Media Attributions

- Figures 10.5.1, 10.5.2: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Kearey and Vine , 1996, Global Tectonics (2ed), Blackwell Science Ltd., Oxford ↵

the concept that at least part of the mechanism of plate motion is the push of oceanic lithosphere down from a ridge area

It’s one thing to know the facts about geological time—how long it is, how we measure it, how we divide it up, and what we call the various periods and epochs—but it is quite another to really understand geological time. The problem is that our lives are short and our memories are even shorter. Our experiences span only a few decades, so we really don’t have a way of knowing what 11,700 years means. What’s more, it’s hard for us to understand how 11,700 years differs from 65.5 million years, or even from 1.8 billion years. It’s not that we can’t comprehend what the numbers mean—we can all get that figured out with a bit of practice—but even if we do know the numerical meaning of 65.5 Ma, we can’t really appreciate how long ago it was.

You may be wondering why it’s so important to really “understand” geological time. There are some very good reasons. One is so that we can fully understand how geological processes that seem impossibly slow can produce anything of consequence. For example, we are familiar with the concept of driving from one major city to another: a journey of several hours at around 100 kilometres per hour. Continents move toward each other at rates of a fraction of a millimetre per day, or something in the order of 0.00000001 kilometres per hour, and yet, at this impossibly slow rate (try walking at that speed!), they can move thousands of kilometres. Sediments typically accumulate at even slower rates—less than a millimetre per year—but still they are thick enough to be thrust up into monumental mountains and carved into breathtaking canyons.

Another reason is that for our survival on this planet, we need to understand issues like extinction of endangered species and anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change. Some people, who don’t understand geological time, are quick to say that the climate has changed in the past, and that what is happening now is no different. And it certainly has changed in the past—many times. For example, from the Eocene (50 Ma) to the present day, Earth’s climate cooled by about 12°C. That’s a huge change that ranks up there with many of the important climate changes of the distant past, and yet the rate of change over that time was only 0.000024°C/century. Anthropogenic climate change has been 1.1°C over the past century,[1]; that is 45,800 times faster than the rate of natural climate change since the Eocene!

One way to wrap your mind around geological time is to put it into the perspective of single year, because we all know how long it is from one birthday to the next. At that rate, each hour of the year is equivalent to approximately 500,000 years, and each day is equivalent to 12.5 million years.

If all of geological time is compressed down to a single year, Earth formed on January 1, and the first life forms evolved in late March (roughly 3,500 Ma). The first large life forms appeared on November 13 (roughly 600 Ma), plants appeared on land around November 24, and amphibians on December 3. Reptiles evolved from amphibians during the first week of December and dinosaurs and early mammals evolved from reptiles by December 13, but the dinosaurs, which survived for 160 million years, were gone by Boxing Day (December 26). The Pleistocene Glaciation got started at around 6:30 p.m. on New Year’s Eve, and the last glacial ice left southern Canada by 11:59 p.m.

It’s worth repeating: on this time scale, the earliest ancestors of the animals and plants with which we are familiar did not appear on Earth until mid-November, the dinosaurs disappeared after Christmas, and most of Canada was periodically locked in ice from 6:30 to 11:59 p.m. on New Year’s Eve. As for people, the first to inhabit B.C. got here about one minute before midnight, and the first Europeans arrived about two seconds before midnight.

It is common for the popular press to refer to distant past events as being “prehistoric.” For example, dinosaurs are reported as being “prehistoric creatures,” even by the esteemed National Geographic Society.[2] The written records of our history date back to about 6,000 years ago, so anything prior to that can be considered “prehistoric.” But to call the dinosaurs prehistoric is equivalent to—and about as useful as—saying that Singapore is beyond the city limits of Kamloops! If we are going to become literate about geological time, we have to do better than calling dinosaurs, or early horses (54 Ma), or even early humans (2.8 Ma), “prehistoric.”

Exercise 8.5 What happened on your birthday?

Using the “all of geological time compressed to one year” concept, determine the geological date that is equivalent to your birthday. First go to Day Number of the Year Calculator to find out which day of the year your birth date is. Then divide that number by 365, and multiply that number by 4,570 to determine the time (in millions since the beginning of geological time). Finally subtract that number from 4,570 to determine the date back from the present.

For example, April Fool’s Day (April 1) is day 91 of the year: 91/365 = 0.2493. 0.2493 x 4,570 = 1,139 million years from the start of time, and 4,570 - 1,193 = 3,377 Ma is the geological date.

Finally, go to the Foundation for Global Community’s “Walk through Time” website to find out what was happening on your day. The nearest date to 3,377 Ma is 3,400 Ma. Bacteria ruled the world at 3,400 Ma, and there’s a discussion about their lifestyles.

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 8.5 answers.