62 10.3 Geological Renaissance of the Mid-20th Century

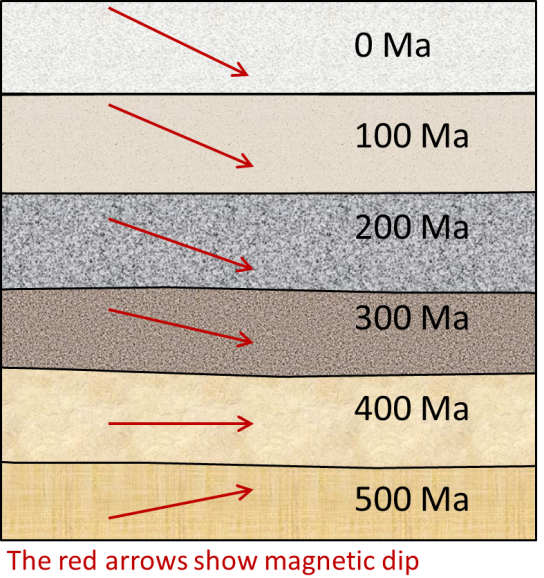

As the mineral magnetite (Fe3O4) crystallizes from magma, it becomes magnetized with an orientation parallel to that of Earth’s magnetic field at that time. This is called remnant magnetism. Rocks like basalt, which cool from a high temperature and commonly have relatively high levels of magnetite (up to 1 or 2%), are particularly susceptible to being magnetized in this way, but even sediments and sedimentary rocks, as long as they have small amounts of magnetite, will take on remnant magnetism because the magnetite grains gradually become reoriented following deposition. By studying both the horizontal and vertical components of the remnant magnetism, one can tell not only the direction to magnetic north at the time of the rock’s formation, but also the latitude where the rock formed relative to magnetic north.

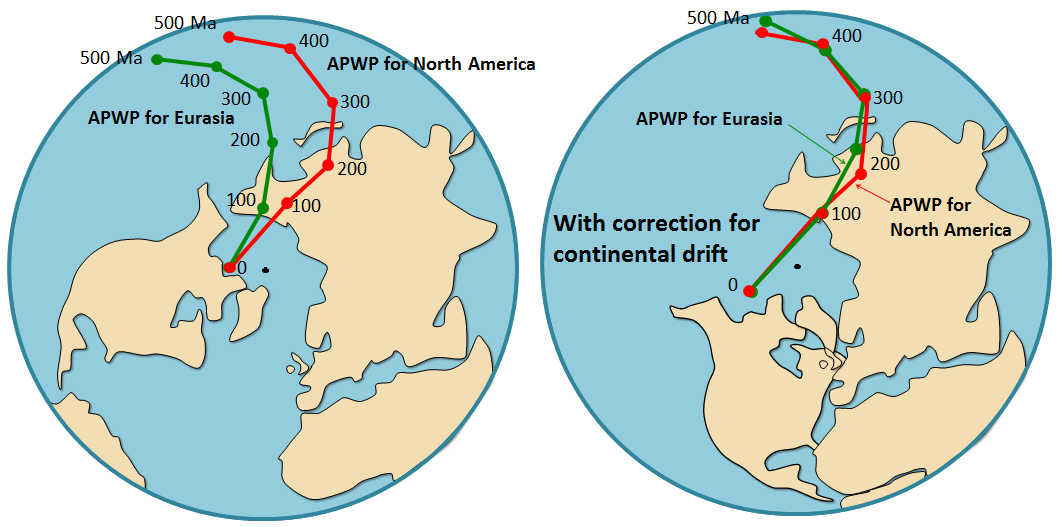

In the early 1950s, a group of geologists from Cambridge University, including Keith Runcorn, Ted Irving,[1] and several others, started looking at the remnant magnetism of Phanerozoic British and European volcanic rocks, and collecting paleomagnetic data. They found that rocks of different ages sampled from generally the same area showed quite different apparent magnetic pole positions (Figure 10.3.1). They initially assumed that this meant that Earth’s magnetic field had, over time, departed significantly from its present position—which is close to the rotational pole.

The curve defined by the paleomagnetic data was called a polar wandering path because Runcorn and his students initially thought that their data represented actual movement of the magnetic poles (since geophysical models of the time suggested that the magnetic poles did not need to be aligned with the rotational poles). We now know that the magnetic data define movement of continents, and not of the magnetic poles, so we call it an apparent polar wandering path (APWP).

At around 500 Ma, what we now call Europe was south of the equator, and so European rocks formed then would have acquired an upward-pointing magnetic field orientation (see Figure 9.3.2 and Figure 10.3.2). Between then and now, Europe gradually moved north, and the rocks forming at various times acquired steeper and steeper downward-pointing magnetic orientations.When researchers evaluated magnetic data in this way in the 1950s, they plotted where the North Pole would have appeared to be based on the magnetic data and assumed that the continent was always where it is now. That means that the 500 Ma “apparent” north pole would have been somewhere in the South Pacific, and that over the following 500 million years it would have gradually moved north.Of course we now know that the magnetic poles don’t move around much (although polarity reversals do take place) and that the reason Europe had a magnetic orientation characteristic of the southern hemisphere is that it was in the southern hemisphere at 500 Ma.Runcorn and colleagues soon extended their work to North America, and this also showed apparent polar wandering, but the results were not consistent with those from Europe. For example, the 200 Ma pole for North America plotted somewhere in China, while the 200 Ma pole for Europe plotted in the Pacific Ocean. Since there could only have been one pole position at 200 Ma, this evidence strongly supported the idea that North America and Europe had moved relative to each other since 200 Ma. Subsequent paleomagnetic work showed that South America, Africa, India, and Australia also have unique polar wandering curves. In 1956, Runcorn changed his mind and became a proponent of continental drift.This paleomagnetic work of the 1950s was the first new evidence in favour of continental drift, and it led a number of geologists to start thinking that the idea might have some merit. Nevertheless, for a majority of geologists working on global geology at the time, this type of evidence was not sufficiently convincing to get them to change their views.

During the 20th century, our knowledge and understanding of the ocean basins and their geology increased dramatically. Before 1900, we knew virtually nothing about the bathymetry and geology of the oceans. By the end of the 1960s, we had detailed maps of the topography of the ocean floors, a clear picture of the geology of ocean floor sediments and the solid rocks underneath them, and almost as much information about the geophysical nature of ocean rocks as of continental rocks.

Up until about the 1920s, ocean depths were measured using weighted lines dropped overboard. In deep water this is a painfully slow process and the number of soundings in the deep oceans was probably fewer than 1,000. That is roughly one depth sounding for every 350,000 square kilometres of the ocean. To put that in perspective, it would be like trying to describe the topography of British Columbia with elevation data for only a half a dozen points! The voyage of the Challenger in 1872 and the laying of trans-Atlantic cables had shown that there were mountains beneath the seas, but most geologists and oceanographers still believed that the oceans were essentially vast basins with flat bottoms, filled with thousands of metres of sediments.

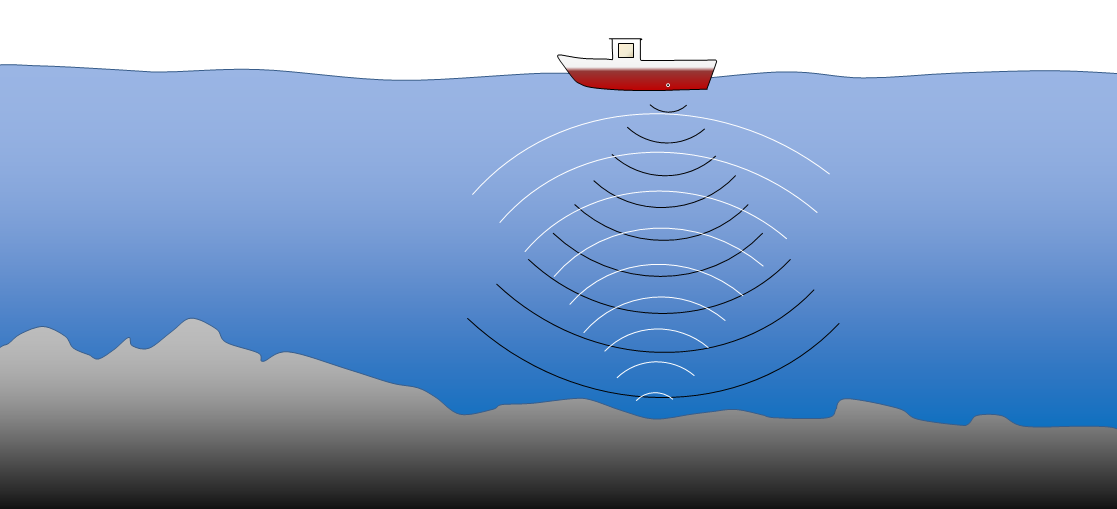

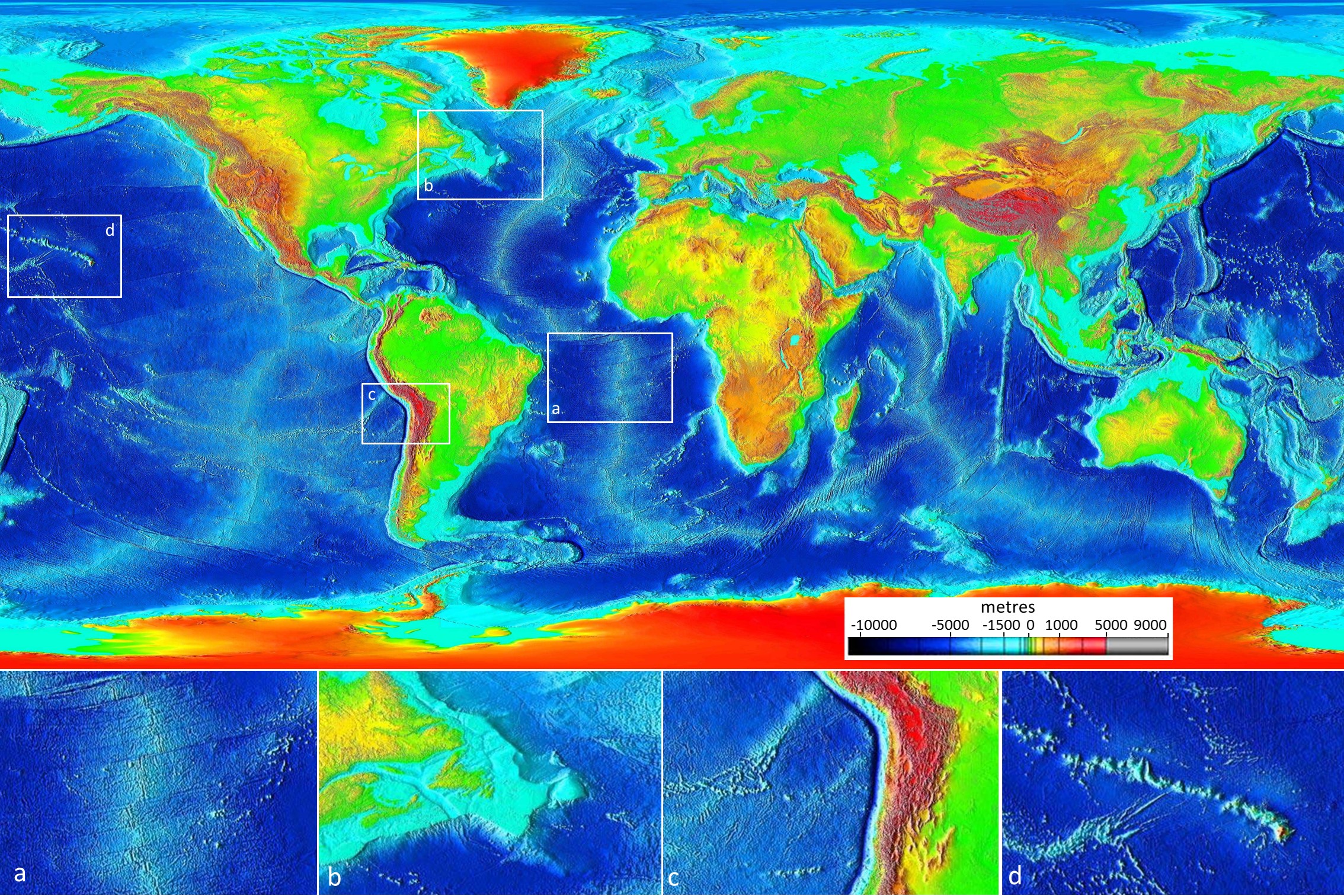

Following development of acoustic depth sounders in the 1920s (Figure 10.3.3), the number of depth readings increased by many orders of magnitude, and by the 1930s, it had become apparent that there were major mountain chains in all of the world’s oceans. During and after World War II, there was a well-organized campaign to study the oceans, and by 1959, sufficient bathymetric data had been collected to produce detailed maps of all the oceans (Figure 10.3.4).

The important physical features of the ocean floor are:

- Extensive linear ridges (commonly in the central parts of the oceans) with water depths in the order of 2,000 to 3,000 m (Figure 10.3.4, inset a)

- Fracture zones perpendicular to the ridges (inset a)

- Deep-ocean plains at depths of 5,000 to 6,000 m (insets a and d)

- Relatively flat and shallow continental shelves with depths under 500 m (inset b)

- Deep trenches (up to 11,000 m deep), most near the continents (inset c)

- Seamounts and chains of seamounts (inset d)

Seismic reflection sounding involves transmitting high-energy sound bursts and then measuring the echos with a series of geophones towed behind a ship. The technique is related to acoustic sounding as described above; however, much more energy is transmitted and the sophistication of the data processing is much greater. As the technique evolved, and the amount of energy was increased, it became possible to see through the sea-floor sediments and map the bedrock topography and crustal thickness. Hence sediment thicknesses could be mapped, and it was soon discovered that although the sediments were up to several thousands of metres thick near the continents, they were relatively thin — or even non-existent — in the ocean ridge areas (Figure 10.3.5). The seismic studies also showed that the crust is relatively thin under the oceans (5 km to 6 km) compared to the continents (30 km to 60 km) and geologically very consistent, composed almost entirely of basalt.

In the early 1950s, Edward Bullard, who spent time at the University of Toronto but is mostly associated with Cambridge University, developed a probe for measuring the flow of heat from the ocean floor. Bullard and colleagues found the rate to be higher than average along the ridges, and lower than average in the trench areas. Although Bullard was a plate-tectonics sceptic, these features were interpreted to indicate that there is convection within the mantle — the areas of high heat flow being correlated with upward convection of hot mantle material, and the areas of low heat flow being correlated with downward convection.

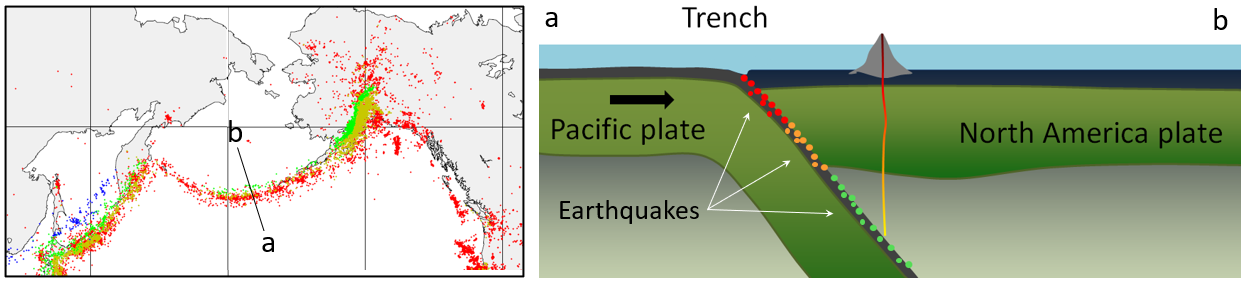

With developments of networks of seismographic stations in the 1950s, it became possible to plot the locations and depths of both major and minor earthquakes with great accuracy. It was found that there is a remarkable correspondence between earthquakes and both the mid-ocean ridges and the deep ocean trenches. In 1954 Gutenberg and Richter showed that the ocean-ridge earthquakes were all relatively shallow, and confirmed what had first been shown by Benioff in the 1930s — that earthquakes in the vicinity of ocean trenches were both shallow and deep, but that the deeper ones were situated progressively farther inland from the trenches (Figure 10.3.6).

In the 1950s, scientists from the Scripps Oceanographic Institute in California persuaded the U.S. Coast Guard to include magnetometer readings on one of their expeditions to study ocean floor topography. The first comprehensive magnetic data set was compiled in 1958 for an area off the coast of B.C. and Washington State. This survey revealed a bewildering pattern of low and high magnetic intensity in sea-floor rocks (Figure 10.3.7). When the data were first plotted on a map in 1961, nobody understood them — not even the scientists who collected them. Although the patterns made even less sense than the stripes on a zebra, many thousands of kilometres of magnetic surveys were conducted over the next several years.

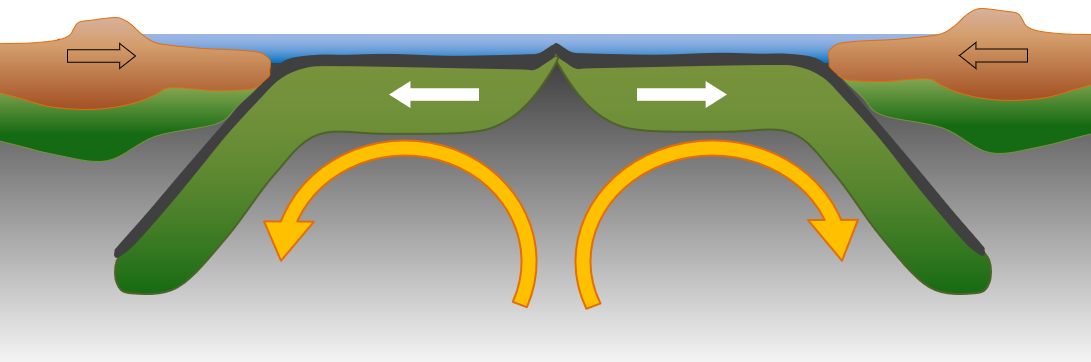

The wealth of new data from the oceans began to significantly influence geological thinking in the 1960s. In 1960, Harold Hess, a widely respected geologist from Princeton University, advanced a theory with many of the elements that we now accept as plate tectonics. He maintained some uncertainty about his proposal however, and in order to deflect criticism from mainstream geologists, he labelled it geopoetry. In fact, until 1962, Hess didn’t even put his ideas in writing—except internally to the U.S. Navy (which funded his research)—but presented them mostly in lectures and seminars. Hess proposed that new sea floor was generated from mantle material at the ocean ridges, and that old sea floor was dragged down at the ocean trenches and re-incorporated into the mantle. He suggested that the process was driven by mantle convection currents, rising at the ridges and descending at the trenches (Figure 10.3.8). He also suggested that the less-dense continental crust did not descend with oceanic crust into trenches, but that colliding land masses were thrust up to form mountains. Hess’s theory formed the basis for our ideas on sea-floor spreading and continental drift, but it did not deal with the concept that the crust is made up of specific plates. Although the Hess model was not roundly criticized, it was not widely accepted (especially in the U.S.), partly because it was not well supported by hard evidence.

Collection of magnetic data from the oceans continued in the early 1960s, but still nobody could explain the origin of the zebra-like patterns. Most assumed that they were related to variations in the composition of the rocks—such as variations in the amount of magnetite—as this is a common explanation for magnetic variations in rocks of the continental crust. The first real understanding of the significance of the striped anomalies was the interpretation by Fred Vine, a Cambridge graduate student. Vine was examining magnetic data from the Indian Ocean and, like others before, he noted the symmetry of the magnetic patterns with respect to the oceanic ridge.

At the same time, other researchers, led by groups in California and New Zealand, were studying the phenomenon of reversals in Earth’s magnetic field. They were trying to determine when such reversals had taken place over the past several million years by analyzing the magnetic characteristics of hundreds of samples from basaltic flows. As discussed in Chapter 9, it is evident that Earth’s magnetic field becomes weakened periodically and then virtually non-existent, before becoming re-established with the reverse polarity. During periods of reversed polarity, a compass would point south instead of north.

The time scale of magnetic reversals is irregular. For example, the present “normal” event, known as the Bruhnes magnetic chron, has persisted for about 780,000 years. This was preceded by a 190,000-year reversed event; a 50,000-year normal event known as Jaramillo; and then a 700,000-year reversed event (see Figure 9.3.3).

In a paper published in September 1963, Vine and his PhD supervisor Drummond Matthews proposed that the patterns associated with ridges were related to the magnetic reversals, and that oceanic crust created from cooling basalt during a normal event would have polarity aligned with the present magnetic field, and thus would produce a positive anomaly (a black stripe on the sea-floor magnetic map), whereas oceanic crust created during a reversed event would have polarity opposite to the present field and thus would produce a negative magnetic anomaly (a white stripe). The same idea had been put forward a few months earlier by Lawrence Morley, of the Geological Survey of Canada; however, his papers submitted earlier in 1963 to Nature and The Journal of Geophysical Research were rejected. Many people refer to the idea as the Vine-Matthews-Morley (VMM) hypothesis.

Vine, Matthews, and Morley were the first to show this type of correspondence between the relative widths of the stripes and the periods of the magnetic reversals. The VMM hypothesis was confirmed within a few years when magnetic data were compiled from spreading ridges around the world. It was shown that the same general magnetic patterns were present straddling each ridge, although the widths of the anomalies varied according to the spreading rates characteristic of the different ridges. It was also shown that the patterns corresponded with the chronology of Earth’s magnetic field reversals. This global consistency provided strong support for the VMM hypothesis and led to rejection of the other explanations for the magnetic anomalies.

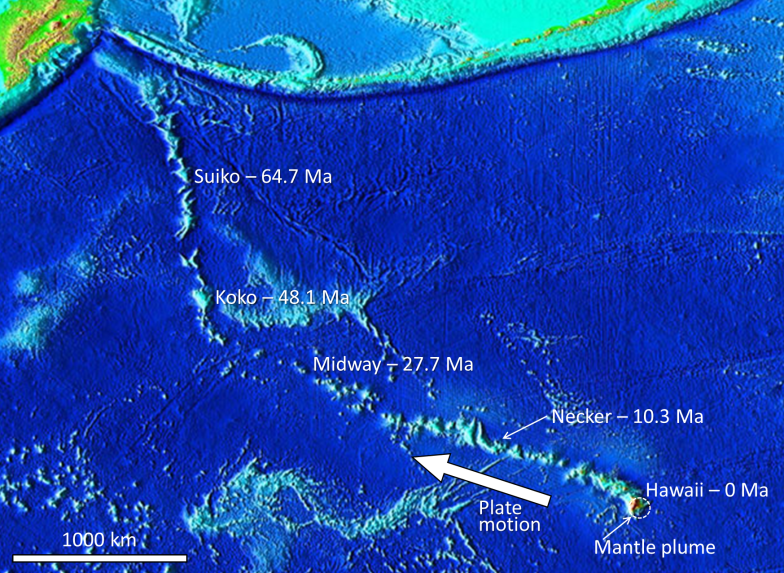

In 1963, J. Tuzo Wilson of the University of Toronto proposed the idea of a mantle plume or hot spot—a place where hot mantle material rises in a stationary and semi-permanent plume, and affects the overlying crust. He based this hypothesis partly on the distribution of the Hawaiian and Emperor Seamount island chains in the Pacific Ocean (Figure 10.3.9). The volcanic rock making up these islands gets progressively younger toward the southeast, culminating with the island of Hawaii itself, which consists of rock that is almost all younger than 1 Ma. Wilson suggested that a stationary plume of hot upwelling mantle material is the source of the Hawaiian volcanism, and that the ocean crust of the Pacific Plate is moving toward the northwest over this hot spot. Near the Midway Islands, the chain takes a pronounced change in direction, from northwest-southeast for the Hawaiian Islands and to nearly north-south for the Emperor Seamounts. This change is widely ascribed to a change in direction of the Pacific Plate moving over the stationary mantle plume, but a more plausible explanation is that the Hawaiian mantle plume has not actually been stationary throughout its history, and in fact moved at least 2,000 km south over the period between 81 and 45 Ma.[2]

Exercise 10.2 Volcanoes and the Rate of Plate Motion

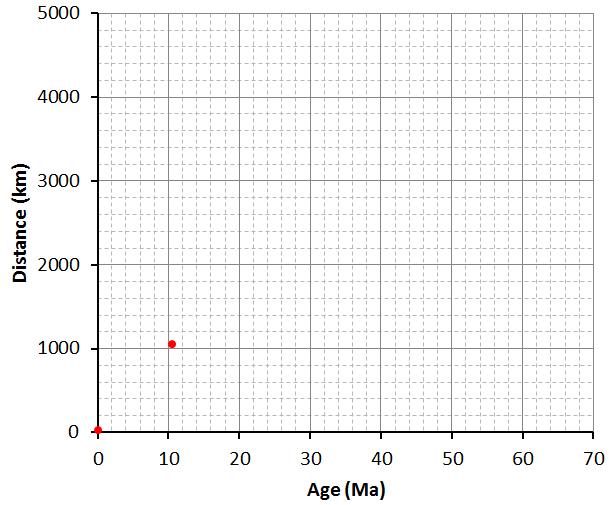

The Hawaiian and Emperor volcanoes shown in Figure 10.3.9 are listed in the table below along with their ages and their distances from the centre of the mantle plume under Hawaii (the Big Island).

| Island | Age | Distance | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hawaii | 0 Ma | 0 km | – |

| Necker | 10.3 Ma | 1,058 km | 10.2 cm/y |

| Midway | 27.7 Ma | 2,432 km | |

| Koko | 48.1 Ma | 3,758 km | |

| Suiko | 64.7 Ma | 4,860 km |

Plot the data on the graph provided here, and use the numbers in the table to estimate the rates of plate motion for the Pacific Plate in cm/year. (The first two are plotted for you.)

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 10.2 answers.

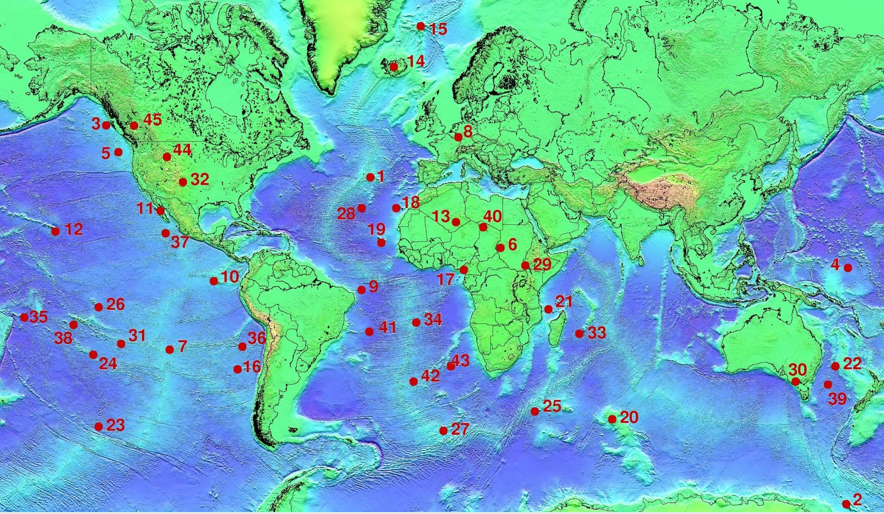

There is evidence of many such mantle plumes around the world (Figure 10.3.10). Most are within the ocean basins—including places like Hawaii, Iceland, and the Galapagos Islands—but some are under continents. One example is the Yellowstone hot spot in the west-central United States, and another is the one responsible for the Anahim Volcanic Belt in central British Columbia. It is evident that mantle plumes are very long-lived phenomena, lasting for at least tens of millions of years, possibly for hundreds of millions of years in some cases.

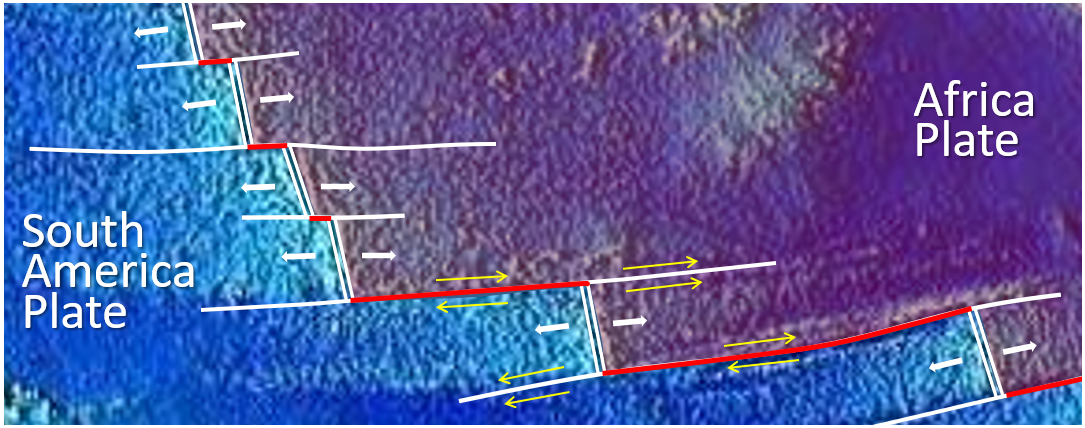

Although oceanic spreading ridges appear to be curved features on Earth’s surface, in fact the ridges are composed of a series of straight-line segments, offset at intervals by faults perpendicular to the ridge (Figure 10.3.11). In a paper published in 1965, Tuzo Wilson termed these features transform faults. He described the nature of the motion along them, and showed why there are earthquakes only on the section of a transform fault between two adjacent ridge segments. The San Andreas Fault in California is a very long transform fault that links the southern end of the Juan de Fuca spreading ridge to the East Pacific Rise spreading ridges situated in the Gulf of California (see Figure 10.4.9). The Queen Charlotte Fault, which extends north from the northern end of the Juan de Fuca spreading ridge (near the northern end of Vancouver Island) toward Alaska, is also a transform fault.

In the same 1965 paper, Wilson introduced the idea that the crust can be divided into a series of rigid plates, and thus he is responsible for the term plate tectonics.

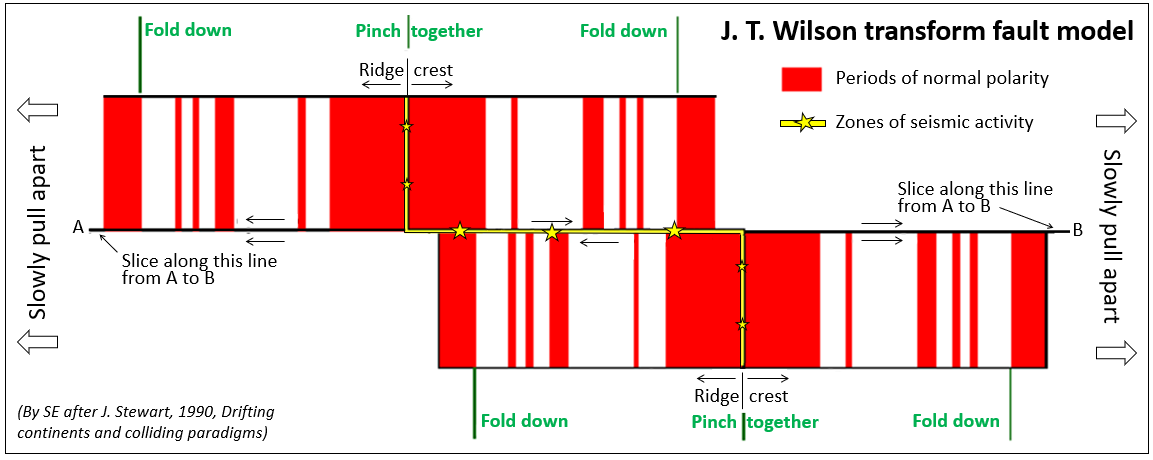

Exercise 10.3 Paper transform fault model

Tuzo Wilson used a paper model, a little bit like the one shown here, to explain transform faults to his colleagues. To use this model either print this page or download the image above and print that, then cut around the outside, and then slice along the line A-B (the fracture zone) with a sharp knife. Fold down the top half where shown, and then pinch together in the middle. Do the same with the bottom half.

When you’re done, you should have something like the example shown on Figure 10.3.13, with two folds of paper extending underneath. Find someone else to pinch those folds with two fingers just below each ridge crest, and then gently pull apart where shown. As you do, the oceanic crust will emerge from the middle, and you’ll see that the parts of the fracture zone between the ridge crests will be moving in opposite directions (this is the transform fault) while the parts of the fracture zone outside of the ridge crests will be moving in the same direction. You’ll also see that the oceanic crust is being magnetized as it forms at the ridge. The magnetic patterns shown are accurate, and represent the last 2.5 Ma of geological time.

There are other versions of this model available here: Paper Models of Transform Faults.[3]

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 10.3 answers.

Image Descriptions

Figure 10.3.2 image description: At 500 Ma, rocks in Europe had upward-pointing magnetic orientations. At 400 Ma, the magnetic orientation leveled. From 300 Ma to the present, rocks in Europe shown an increasingly downward-pointing magnetic orientation. [Return to Figure 10.3.2]

Figure 10.3.6 image description: A cross section of the trench formed at the Aleutian subduction zone as the Pacific plate subducts under the North American plate in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The farther away an earthquake is from this trench (on the North America plate side), the deeper it is. [Return to Figure 10.3.6]

Media Attributions

- Figures 10.3.1, 10.3.2, 10.3.3, 10.3.5, 10.3.6, 10.3.8, 10.3.11, 10.3.12, 10.3.13: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

- Figure 10.3.4: “Elevation” by NOAA. Adapted by Steven Earle. Public domain.

- Figure 10.3.7: “Juan de Fuca Ridge” by USGS. Adapted by Steven Earle. Public domain. Based on Raff, A. and Mason, R., 1961, Magnetic survey off the west coast of North America, 40˚ N to 52˚ N latitude, Geol. Soc. America Bulletin, V. 72, p. 267-270.

- Figure 10.3.9: “Hawaii Hotspot” by National Geophysical Data Center. Adapted by Steven Earle. Public domain.

- Figure 10.3.10: “Hotspots” by Ingo Wölbern. Public domain.

- Ted Irving later set up a paleomagnetic lab at the Geological Survey of Canada in Sidney, B.C., and did a great deal of important work on understanding the geology of western North America. ↵

- J. A. Tarduno et al., 2003, The Emperor Seamounts: Southward Motion of the Hawaiian Hotspot Plume in Earth’s Mantle, Science 301 (5636): 1064–1069. ↵

- For more information see: Earle, S., 2004, A simple paper model of a transform fault at a spreading ridge, J. Geosc. Educ. V. 52, p. 391-2. ↵

Learning Objectives

After carefully reading this chapter, completing the exercises within it, and answering the questions at the end, you should be able to:

- Explain why rocks formed at depth in the crust are susceptible to weathering at the surface.

- Describe the main processes of mechanical weathering, and the types of materials that are produced when mechanical weathering predominates.

- Describe the main processes of chemical weathering, and the products of chemical weathering of minerals such as feldspar, ferromagnesian silicates, and calcite.

- Explain the type of weathering processes that are likely to have taken place to produce a particular sediment deposit.

- Discuss the relationships between weathering and soil formation, and the origins of soil horizons and some of the different types of soil.

- Describe and explain the distribution of some of the important soil types in Canada.

- Explain the geological carbon cycle, and how variations in rates of weathering can lead to climate change.

Weathering is what takes place when a body of rock is exposed to the "weather"—in other words, to the forces and conditions that exist at Earth's surface. With the exception of volcanic rocks and some sedimentary rocks, most rocks are formed at some depth within the crust. There they experience relatively constant temperature, high pressure, no contact with the atmosphere, and little or no moving water. Once a rock is exposed at the surface, which is what happens when the overlying rock is eroded away, conditions change dramatically. Temperatures vary widely, there is much less pressure, oxygen and other gases are plentiful, and in most climates, water is abundant (Figure 5.01).

Weathering includes two main processes that are quite different. One is the mechanical breakdown of rock into smaller fragments, and the other is the chemical change of the minerals within the rock to forms that are stable in the surface environment. Mechanical weathering provides fresh surfaces for attack by chemical processes, and chemical weathering weakens the rock so that it is more susceptible to mechanical weathering. Together, these processes create two very important products, one being the sedimentary clasts and ions in solution that can eventually become sedimentary rock, and the other being the soil that is necessary for our existence on Earth.

The various processes related to uplift and weathering are summarized in the rock cycle in Figure 5.02.

Image Descriptions

Figure 5.02 image description: “The Rock Cycle.” The rock cycle takes place both above and below the earth’s surface. The rock deepest beneath the earth’s surface and under extreme heat and pressure is metamorphic rock. This metamorphic rock can melt and become magma. When magma cools, if below the earth’s surface it becomes “intrusive igneous rock.” If magma cools above the earth’s surface it is “extrusive igneous rock” and becomes part of the outcrop. The outcrop is subject to weathering and erosion, and can be moved and redeposited around the earth by forces such as water and wind. As the outcrop is eroded, it becomes sediment which can be buried, compacted, and cemented beneath the earth’s surface to become sedimentary rock. As sedimentary rock gets buried deeper and comes under increased heat and pressure, it returns to its original state as metamorphic rock. Rocks in the rock cycle do not always make a complete loop. It is possible for sedimentary rock to be uplifted back above the Earth’s surface and for intrusive and extrusive igneous rock to be reburied and became metamorphic rock. [Return to Figure 5.02]

Media Attributions

- Figures 5.0.1, 5.0.2: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

Intrusive igneous rocks form at depths of several hundreds of metres to several tens of kilometres. Sediments are turned into sedimentary rocks only when they are buried by other sediments to depths in excess of several hundreds of metres. Most metamorphic rocks are formed at depths of kilometres to tens of kilometres. Weathering cannot even begin until these rocks are uplifted through various processes of mountain building—most of which are related to plate tectonics—and the overlying material has been eroded away and the rock is exposed as an outcrop.[1]

The most important agents of mechanical weathering are:

- The decrease in pressure that results from removal of overlying rock

- Freezing and thawing of water in cracks in the rock

- Formation of salt crystals within the rock

- Cracking from plant roots and removal of material by burrowing animals

When a mass of rock is exposed by weathering and removal of the overlying rock, there is a decrease in the confining pressure on the rock, and the rock expands. This unloading promotes cracking of the rock, known as exfoliation, as shown in the granitic rock in Figure 5.1.1., which, in places, is peeling off like the layers of an onion.

Granitic rock tends to exfoliate parallel to the exposed surface because the rock is typically homogenous, and it doesn’t have predetermined planes along which it must fracture. Sedimentary and metamorphic rocks, on the other hand, tend to exfoliate along predetermined planes (Figure 5.1.2).

Frost wedging is the process by which water seeps into cracks in a rock, expands on freezing, and thus enlarges the cracks (Figure 5.1.3). The effectiveness of frost wedging is related to the frequency of freezing and thawing. Frost wedging is most effective in a climate like Canada’s. In warm areas where freezing is infrequent, in very cold areas where thawing is infrequent, or in very dry areas, where there is little water to seep into cracks, the role of frost wedging is limited. If you are ever hiking in the mountains you might hear the effects of frost wedging when the Sun warms a steep rocky slope and the fragments of rock that were pried away from the surface by freezing the night before are released as that ice melts.

In many parts of Canada, the transition between freezing nighttime temperatures and thawing daytime temperatures is frequent — tens to hundreds of times a year. Even in warm coastal areas of southern B.C., freezing and thawing transitions are common at higher elevations. A common feature in areas of effective frost wedging is a talus slope—a fan-shaped deposit of fragments removed by frost wedging from the steep rocky slopes above (Figure 5.1.4).

A related process, frost heaving, takes place within unconsolidated materials on gentle slopes. In this case, water in the soil freezes and expands, pushing the overlying material up. Frost heaving is responsible for winter damage to roads all over North America.

When salt water seeps into rocks and then evaporates on a hot sunny day, salt crystals grow within cracks and pores in the rock. The growth of these crystals exerts pressure on the rock and can push grains apart, causing the rock to weaken and break. There are many examples of this on the rocky shorelines of Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, where sandstone outcrops are common and salty seawater is readily available (Figure 5.1.5). Salt weathering can also occur away from the coast, because most environments have some salt in them.

The effects of plants and animals are significant in mechanical weathering. Roots can force their way into even the tiniest cracks, and then they exert tremendous pressure on the rocks as they grow, widening the cracks and breaking the rock (Figure 5.1.6). Although animals do not normally burrow through solid rock, they can excavate and remove huge volumes of soil, and thus expose the rock to weathering by other mechanisms.

Mechanical weathering is greatly facilitated by erosion, which is the removal of weathering products, allowing for the exposure of more rock for weathering. A good example of this is shown in Figure 5.1.4. On the steep rock faces at the top of the cliff, rock fragments have been broken off by ice wedging, and then removed by gravity. This is a form of mass wasting, which is discussed in more detail in Chapter 15. Other important agents of erosion that also have the effect of removing the products of weathering include water in streams (Chapter 13), glacial ice (Chapter 16), and waves on the coasts (Chapter 17).

Exercise 5.1 Mechanical weathering

This photo shows granitic rock at the top of Stawamus Chief near Squamish, B.C. Identify the mechanical weathering processes that you can see taking place, or you think probably take place at this location.

See Appendix 3 for Exercise 5.1 answers.

Media Attributions

- Figures 5.1.1, 5.1.2, 5.1.3, 5.1.4, 5.1.5, 5.1.6, 5.1.7: © Steven Earle. CC BY.

a path of varying magnetic pole positions defined by paleomagnetic data (in fact it is now understood that the continents have wandered, not the poles, so a more appropriate terms is “apparent polar wandering path”)

measurement of the properties of sediments based on detection of sounds generated at surface and reflected from layers beneath the surface

The concept that the Earth’s crust and upper mantle (lithosphere) is divided into a number of plates that move independently on the surface and interact with each other at their boundaries.

the formation of new oceanic crust by volcanism at a divergent plate boundary

the concept that tectonic plates can move across the surface of the Earth

a region of the lithosphere that is considered to be moving across the surface of the Earth as a single unit

a plume of hot rock (not magma) that rises through the mantle (either from the base or from part way up) and reaches the surface where it spreads out and also leads to hot-spot volcanism

the surface area of volcanism and high heat flow above a mantle plume

a boundary between two plates that are moving horizontally with respect to each other