1

Zanele Muholi, a Black lesbian South African artist, was born in 1972 in Umlazi, Durban, the fourth largest township in South Africa. Born to a mother who was a domestic worker, Muholi was born at the height of apartheid. She was only four years old when the 1976 Soweto Uprisings led to rebellious children being killed by state violence. 1976 is when the world got to see the actual horrors of the Apartheid state.

The visual history of this country has always been hidden. What happened in South Africa? Only do we see a 1994 victory moment with Nelson Mandela’s hands stretched out towards the masses as if he was the second coming of Christ. Visually, Nelson Mandela had risen like Christ after twenty-seven years of incarceration on Robben Island. Sixteen years later we see the progress of this country via televised sports play: the World Cup 2010. What is happening in South Africa? Remember that solidarity moment in the eighties? Spike Lee’s movie plots about apartheid, connections to the Jim Crow South, Berkeley students protesting for divestment while brutalized by the campus militarized police. Remember that moment? What does South Africa mean to the rest of us now? Does it remain as the moment where international solidarity prevailed? What does South Africa mean to us now?

Muholi emerges from this historical moment in the African Diaspora’s perpetual quest to escape the afterlife of slavery. Her call is to pursue visual activism in the post-apartheid visual landscape. Her insurgence is a critique of the carefully curated regime of the Rainbow Nation to show a false sense of simunye (oneness). South Africa is not one, not yet. The trauma still exists for the Born Frees. We still see barriers to access to institutions of survival. With the 2015 protest of Rhodes Must Fall at the University of Cape Town and across South Africa, visual imagery disrupted the notion that South Africa is actually in a “post-apartheid” state and proved that it is in fact still structurally functioning as an apartheid state.

South Africa is also praised for its progressive LGBT legislation. In 1996, when South Africa was creating their new constitution once apartheid ended, Section Nine (also known as the Equality clause) was created to protect populations from sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination. South Africa was the first country in the world to do this legally. In 2006, South Africa passed the Civil Union Act, which made it the first country in Africa to pass same-sex marriage laws. South Africa was technically more progressive than its queer culture hegemonic partner: the United States of America. I use this history to situate Muholi’s work as a disruption to these sanitized understandings of progress.

Muholi is drawing attention to a state of emergency in her earlier works with the Black Lesbian Body as her primary focus. She exposes the irony of calling South Africa the “gay capital of Africa,” because who is this gay capital really for? Settler Homonationalism, as theorized by Scott Lauria Morgensen (by way of Jasbir Puar), helps one understand the geographic assemblage Muholi is critiquing. When one speaks about South Africa being the “gay capital of Africa” that insinuates new queer modernities have been produced as a function of a settler-colonial politic[1]. Strategically, Muholi’s work takes witness to the Black lesbian in the township. The township is not the place people think of when people hear “the gay capital of Africa,” and Muholi knows that and intentionally uses that space to center her discourse.

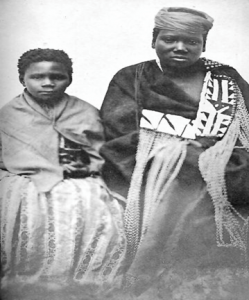

Only Half the Picture is Muholi’s 2006 debut exhibit at the Michael Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town. The reception was highly celebrated, but I argue the collection is largely under-theorized. Much of Muholi’s critical praise was for Faces and Phases: 2006-2014, a collection of 240 portraits of Black Lesbian women from primarily South Africa, but also Botswana, Mozambique, and Canada. The conceptual framework around this project was to document and archive the lives of Black lesbians in direct response to the uncertainty of Black lesbian existence in South Africa, due to the rise of hate crime murders of lesbians. Muholi once referred to these killings as Black lesbian genocide. Faces and Phases is a larger meditation on what it means to document and provide visibility to the lesbian body. Muholi is simply returning the gaze. However, in Only Half the Picture I am pulling much more conceptual work from Muholi. Many of the images are from 2003. Only nine years out of apartheid, and here is a heavy commentary on what apartheid remains have done to the black lesbian body. Muholi is essentially exploring Black female subjectivities within the post-apartheid South African context.

Black South African Feminist scholar Gabi Ngcobo comments on how the black lesbian body is the subject of daily interrogation. This interrogation comes from a misunderstanding of the existence of the black lesbian subject as if this body is only a contemporary phenomenon. Homosexuality is un-African. Homosexuality is white. You think you are a man? Let me show you are not. “Images compel us to realize that the invisible…was never ‘not not there’” (Ngcobo 4). Muholi’s debut work transgresses political boundaries and social taboos because she asserts that lesbians exist, naturally. These people are in your township, and they are your relatives. To further this assertion, “the work is less about making black lesbians visible than it is about engaging with the regimes that have used these women’s hypervisibility as a way to violate them,” (Ngcobo 4). The township is a regime that makes the black lesbian body hypervisible, vulnerable to the violation of all the pain that has not been reconciled with the apartheid past. A promise of freedom in the transitional democracy has left many dispossessed, and looking for a place to cast blame. The Black lesbian body is in essence, in exile from itself.

Black Feminist South African scholar Pumla Dineo Gqola’s article “Through Zanele Muholi’s eyes: Re/imagining ways of seeing black lesbians” helps understand the impact of Muholi’s visual talent. What Black Art canon will Muholi fit into? Where does she belong? Her archive is the underground, a covert project decoded with logic for liberation. “While we may immediately want to define the specific aesthetic bent of her work, fix her precise location, and conclusively identify the traditions from which she draws, Muholi’s work as contained in this collection resists precisely such endeavors to name, tame and classify” (Gqola 83). The process of being a student of Muholi’s work has taught me to read slow, understand the evolution of thought. We see these pictures and want to piece it all together. I try to find myself within these women; I try to read them to know if we share the same pain. Do we share the same story? I have the same scar, but not in the same place. The differentiation is a diasporic critique in itself; what makes us different is the context that forces modernity into our intimacies.

Muholi’s work is not easily digestible. There is a higher calling in the work. The images of Muholi cannot just be swallowed and appreciated in a gallery walk. “It requires that we do more than safely admit that Black lesbians exist” (Gqola 83). The techniques and effects employed by Muholi are enough to establish her own canon of thought. Thus, this inquiry is not a meditation solely on the aesthetic value of Muholi’s work; there is something more to be considered. Muholi’s work is fugitive, an insurgence to suffocating perceptions of the Black lesbian body. Black lesbians are not invisible. There are many names for a woman who has established self-determination in her pleasure; these women “are in fact highly visible manifestations of the undesirable” (Gqola 83). The consequences lead to social expulsion from communities, families, and to higher risks of sexual violence and murder. The black lesbian body is not invisible; the black lesbian body is hunted and her pleasure is fugitive.

Only Half the Picture speaks to the impossibility of effective containment of the Black lesbian body. The black lesbian will not be held in a place to hide her desires. There is a constant violation and co-optation of Black lesbian lives. Discourses want to reproduce the violence Black lesbians face, without investment in highlighting the social life of black lesbians. To extend, “Voyeuristic imagining of lesbians’ sexual intercourse permeates the spectrum of patriarchal fantasy” (Gqola 86). Muholi’s work shows how speaking oneself into normativity is impossible at times, because the representational system hegemonically belongs to hetero/sexuality. Muholi’s interpretive authority of Black lesbian lives is an assertion to look beyond the violence, eroticism and see moments of survival.

For Muholi’s work, pleasure is central to attaching certain meanings and connotations to the Black female body. How does the material expression of Black lesbian desire relate to the larger discourses of possessions and dispossessions in a post-apartheid South Africa? The political and socio-cultural imperialism of British and Afrikaner violence of the past render the Black lesbian stranger and searching for empowering meaning in Native spaces. It is as if the black lesbian body represents the downfall of a great African past. Animosity emerges. The Black lesbian body is the story of Nongqawuse. Nongqawuse’s prophecy tells of how a young sangoma/spiritual leader is told to kill all the livestock to prevent English settlers[2] from invading the Eastern Cape. She received a “calling” from her ancestors, warning the Xhosa people of colonial expansion. This is a myth that reigns supreme in the national imaginary. The Xhosa’s livestock was infected with a lung disease that led to cows dying, and as a result, the Eastern Cape population fell from 105,000 to 27,000 due to death from famine. Nongqawuse’s spiritual prophecy created a negative relation with relying on sangomas for communal direction. People dismissed it as simple umuthi– witchcraft. She was imprisoned to life at Robben Island and died in 1898. This spiritual healer, the witch doctor, is responsible for mass dispossession for the Native. This moment in history is known as the Great Cattle-Killing Movement of 1856.

I use the Black lesbian body, as an extension of Nongqawuse’s containment after her prophecy did not come true. The black lesbian orator is seen as the spiritual leader in today’s times. The Black queer testimony is supposed to liberate and show us the way to freedom; however, she failed her community, created a loss of reproduction, and distracted us in a way that led to dispossession.

I use the Black lesbian body, as an extension of Nongqawuse’s containment after her prophecy did not come true. The black lesbian orator is seen as the spiritual leader in today’s times. The Black queer testimony is supposed to liberate and show us the way to freedom; however, she failed her community, created a loss of reproduction, and distracted us in a way that led to dispossession.

I use Nongqawuse[3] to tell the story about how Black lesbian bodies are projected onto as traitors of the nation-state project for black liberation. Nongqawuse’s calling is the same calling that Black lesbians get when they choose to step into their identity and soul hunger to love women. The spirit calls for the Black lesbian to speak of discontinuities in notions of community. Nongqawase’s calling was a valid one, but it was one before its time. This led the Xhosa people to release her to the state and imprison her as punishment. Nongqawuse forced the Native into modernity, resulting in the community rebelling against spiritual guidance. The impact of Nongqawuse’s prophecy not coming to life, (even though British expansion did happen in the region much later) led to forced modernity of traditional society. How does it feel to be a problem?

The black lesbian body induces the same transitions in the national narrative of post-apartheid South Africa as Nongqawase. The Black lesbian body is either a representation of Black women’s autonomy or queer sexuality as unAfrican. Nongqawuse prophecy’s was unAfrican as it led to Xhosa culture diminishing due to death by famine, thus making it more vulnerable to colonial expansion due to the dearth population. The Black lesbian body is not to blame for the lack of progress in a post-apartheid South Africa, but the consequences are punitive onto the Black lesbian body just as easily as Nongqawase was released to state confinement.

Notions of LGBT progress and racial desegregation in a post-apartheid South Africa supposedly render the Black lesbian body safe to exist in their full self-determination; however, this is false. Violent regimes of patriarchy and white monopoly capital still perpetuate a social death of Black lesbian existence. Gqola notes, “this is one of the most central, and effective, features of all oppressive systems: the ability to act with unrelenting violence towards the demonized at the same time that dominant epistemic routes deny the existence of hegemony,” (Gqola 87). The hegemony of heteronormative nationalisms has killed Black lesbians from the English, the Afrikaners, and now the African National Congress’ denial of the crises[4].

[1] To extend, I am asserting that the “gay capital of Africa” notion is a product of historically displacing Black Natives from their own land. Black people overwhelmingly still live in the informal settlements that were administered by apartheid. When referring to the gay capital, it is only a reference to De Waterkant neighborhood ( a gay neighborhood that was once a coloured community prior to the Group Areas Act of 1955). The Black South Africans is still displaced in their own land because post-apartheid is not a regime of land redistribution. The homonationalist project of calling South Africa the gay capital via legal laws and gayborhoods, is actually just an extension of settler homonationalism as theorized in Morgensen, Scott Lauria. “SETTLER HOMONATIONALISM Theorizing Settler Colonialism within Queer Modernities.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 16.1-2 (2010): 105-131.

[2] William W. Gqoba (1888), Xhosa poet and historian, retells the story of Nongqawuse. She was instructed by the ancestors appearing to her to: “Tell that the whole community will rise from the dead; and that all cattle now living must be slaughtered, for they have been reared by contaminated hands because there are people about who deal in witchcraft. There should be no cultivation, but great new grain pits must be dug, new houses must be built, and great strong cattle enclosures must be erected. Cut out new milksacks and weave many doors from bukka roots [administered to young women to make them pregnant and prevent miscarriages]. So says the chief Napakade, the descendant of Sifuba-Sibanzi. The people must leave their witchcraft, for soon they will be examined by diviners.[ … ] See more Stapleton, Timothy J. “” They No Longer Care for Their Chiefs”: Another Look at the Xhosa Cattle-Killing of 1856-1857.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 24.2 (1991): 383-392.

[3] For a deeper analysis on the impact of Nongqawuse’s prophecy on the gendered confinement of post- apartheid South Africa nationalism please see Samuelson, M. A. Remembering the nation, disremembering women?: stories of the South African transition. Diss. University of Cape Town, 2005.

[4] In 2009, Arts and Culture Minister Lulu Xingwana called Muholi’s work “immoral” and “pornographic”. Muholi responded by saying “In South Africa, where we have corrective rapes and violence against lesbians happening in the townships, we have to be careful. When a minister, or someone in a position of power, makes homophobic comments, it could perpetuate hate crimes. You might be putting people at risk. This issue goes beyond art” For more see: https://mg.co.za/article/2010-03-05-xingwana-homophobic-claims-baseless-insulting

.